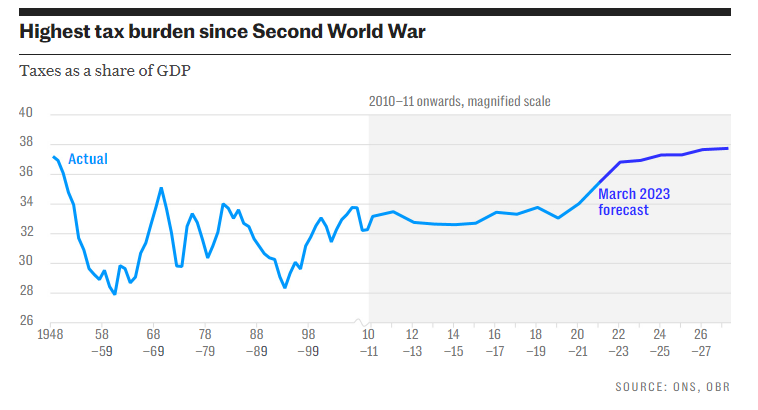

Kate Andrews has done a great job in the Telegraph reminding readers that a major source of our current economic malaise – now approaching the highest tax burden since records began 75 years ago – is the cost and impact of the Covid lockdowns, a price which must never be forgotten. Here’s how she begins.

Ideally we’d never talk about lockdown again. We’d consign those draconian years to the history books and get on with normal life.

Unfortunately, there remains far too big a mess to clean up to bury those memories completely. The thousands of children who never returned to school, the millions of people on NHS waiting lists – these are people we must not forget.

But some lockdown legacies are discussed more widely than others. Those waiting lists are a big part of the public debate, rising to 7.6m (and counting) in England.

Lost learning also remains pertinent, as other impediments to schooling this year kept it in the news. Teacher strikes and crumbling school buildings provided cumulative reminders that, between March 2020 and April 2021, pupils were estimated to have had their learning hours reduced by a third.

What we don’t talk about as much are the long-term spending ramifications of the pandemic. …

It suits every political party not to talk about the longer-term spending trajectory Covid has set us on. If you dare look at where we’re headed, it becomes impossible to keep up the pretence that the sums of money we’re spending, or the promises we continue to make, are in any way sustainable.

There’s an irony in political discourse: that as our spending trajectory has gone off the deep end, both the Conservatives and Labour have adopted the language of fiscal responsibility.

This has always been Rishi Sunak’s selling point: that he is ready to make difficult decisions to get the books (somewhat) balanced.

Labour, while light on detail, has largely promised to do the same and has even been willing to take some political pain (like watering down its £28bn pledge on green investment) to show that it is serious about making the numbers add up.

But that language is not lining up with policy. The aftermath of the pandemic has created far greater demand for health and welfare than can be met, even with rising tax receipts that reflect the highest tax burden in over 70 years.

The number of people out of work due to long-term sickness has increased by roughly half a million, taking the total to 2.6 million; the number of people on out-of-work benefits since the furlough scheme has risen to over five million.

Include rising pension payouts and the total nominal welfare bill is projected to increase by 16% between now and 2027-28, according to the Department for Work and Pensions.

Meanwhile, the NHS bill is only going up, set to amount to 44% of all day-to-day public spending in just a few years’ time.

With access to healthcare already so appalling – going into flu season no less – and the ongoing doctors strikes further deteriorating services, it’s near impossible to see how the £13bn promised for social care ever ends up being redirected away from the health service.

These are the practical spending problems that lockdown has created, but they only begin to highlight the financial mess we’re in.

The trouble is, says Andrews, thanks to the lockdowns “we have entered an era where demand for government intervention is sky-high”.

“No one is fixing the roof when it’s raining or it’s shining,” she adds.

Worth reading in full.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

https://off-guardian.org/2023/09/29/soul-muscles/

Of Klaus Schwab:

“He has groomed and put charismatic ambitious young things in charge of countries while failing miserably to understand that these leaders haven’t got a clue how to talk to real people.

But worst of all, it would appear they can only accept praise and adoration. We are either children without a brain in our head to be commanded or baskets of deplorables or at least of no concern at all. These poor leaders are very unhappy with criticism.”

From a short piece by Sylvia Shawcross at Off-G.

Yes lockdowns did cause an enormous amount of suffering but I still think it was planned. There were different ways to keep the economy afloat. Wasting taxpayers money in the billions on a useless track and trace system and countless millions more on

Whoops…unfinished comment! Meant to add:

on PPE, HS2, Ukraine etc and all thanks to the bank of you and me, the real magic money tree, didn’t help of course. Tax rebellion would be great but as someone pointed out, many are taxed at source so it’s just not possible. Anyway, the planned destruction of our economy and of the working/middle classes leading to owning nothing and being happy about it! If we ever were locked down again, it would ruin us. We must therefore never let it happen.

It is possible to hold back tax at source (legally). All taxes (and fines) go into a Parliamentary Consolidated Fund – 230 of them including VAT, parking tickets, student loans etc. The gov then uses 5-10% of this money on illegal wars (and false flags) thereby breaking the law. It is illegal in this country to pay tax knowing the money can be spent on illegal activity. The way around it, is you don’t refuse to pay tax, you put your tax in Trust (as the oligarchs and many MPs do) with the gov/HMRC as Primary Beneficiary and you tell them they can collect the tax so long as your demands are met. They of course can’t prove the tax isn’t used for criminal purposes and you can then use your tax to pay towards things you care about like home-schooling or whatever. Consolidated Fund: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1018479/CCS0921300720-001_HMT_Consolidated_Fund_CF_Web_Accessible.pdf

Chris Coverdale has written a lot on this – he was also on Vobes.

I’m in the lucky position of having no debt; a decent level of savings/ investments/pensions. A few years ago I decided to simplify and de-stress my life; I moved to the west country, downsized and found a “little” part-time job, mainly to keep me occupied.

I now actively minimise the amount of tax I pay. I don’t pay NI; only a little Income Tax and by being careful who and what I spend on, I minimise VAT. I’m enjoying depriving this appalling Government of as much of my money as I possibly can.

Firstly, Lockdowns didn’t get us in to this mess, lackey politicians did.

What’s missing from this synopsis? Any attempt to ask why.

Why was public spending allowed to reach stratospheric levels when O’level economics would confirm only that disaster would ensue?

Why is the country still being driven towards implosion with energy policies that have collapse and disaster baked in?

Why is the destruction of a free press now such an integral part of government policy?

Why is our MSM nothing more than Orwell’s Ministry of Truth pumping out daily lies and propoganda and brooking no dissent?

Why are the sad remnants of heavy industry such as coal, automotive and steel being given the coup de grace while ensuring no replacement industries are available?

Why are citizens being threatened over the manner in which they manage their own homes? In 2023 in a supposedly First world democracy – yeah right.

Why are we deliberately encouraging third world immigrants who have no interest in this country other than to rape and rape metaphorically and who despise their hosts?

On the face of it the article merits a nod but the reality is it achieves nothing. Far from entering “an era where demand for government intervention is sky-high” we have entered an era where, if things were to be dealt with in a logical and sensible manner the government would abandon ALL post Brexit legislation, sort out the definitive BREXIT and allow decent people to rebuild their lives. But that’s not going to happen is it because the real goal of the Davos Deviants is the wholesale destruction of Britain and the West; destruction even to dust? Concomitant is the eradication of the population. The Online Harms Bill is all about protecting children – how thick do they think we are?

In order to ensure the lies and propoganda work there must be only one source of truth – ain’t that right Jacinda? Obviously as the deaths mount – its coming – independent news outlets shouting the real stories cannot be allowed. We are to be locked into a nullifying state of censorship and propoganda exactly as practiced by the Nazis in the 1930’s.

The Lockdowns were deliberate and the intent was to drag us to where we are now. Having missed the starting point Kate Andrews’ conclusions can only reach the wrong destination. Failing to see the bigger picture will result in some left / right argy bargy but behind the scenes the Agenda 2030 program will march slowly to its conclusion. If the march is successful few of us will see it. For those that do, I hope they have read Orwell’s 1984 because it will be their daily reading.

Fabulous stuff, HP! You’re on fire!

Many thanks Aethelred.

👏👍🎯

Thank you Mogs 😊

**Off-territory dump incoming. Stand by your pitch forks!**

I can’t believe this. What’s happening over at GBN?? 😮

”Calvin Robinson SUSPENDED from GB News!

Calvin stands for Christian and family values and has been at many protests walking the walk as well.

Everyone should give Calvin their support as there is a much bigger fight at play!”

https://twitter.com/UnityNewsNet/status/1707710465466331332

I wonder if it was anything to do with his earlier tweet which was supportive of Dan Wootton. Here’s an excerpt. I fully concur and thought this was excellent actually;

”I will not be appearing on Dan Wootton Tonight without Dan Wootton.

Dan Wootton had a significant part to play in building GB News.

He invited me along pre-launch, he also brought so many people onboard. Behind the cameras as well as on-screen talent.

Including the careerist ambitious ones who are currently gunning for his job. These people are worse than the woke mob, because these vultures are giving the mob ammunition and essentially escalating the channel’s demise.

We failed as a community to stand up for Mark Steyn. If we let them do the same to Dan, it’s over. The channel will be on borrowed time, we will all be the next in the firing line.”

https://twitter.com/calvinrobinson/status/1707663197853880449

Steyn, Calvin, Wootton, Fox, soon Oliver….GB news is being systematically extirpated. Advertisers told to stay away. Calvin R is the least offensive person imaginable. But he is a Christian (as am I), so he must be gotten rid of (say TPTB). Thriving democracy, freedom, values and all that BS.

“According to the comments section over at TCW Calvin Robinson has been suspended for supporting Dan Wootton.

Firkin unbelievable.

GB News is killing itself.

Get a grip you cowards!”

Mogs, my post over on the previous ATL article – Covid backpedalling -posted at about 13:30.

Keep up lass.

I can’t keep up!😆 Mind I have had to step away from t’internet here and there so I didn’t clock your post. Actually I still can’t find it just now…Been a bit lively round these parts today.

I am gutted about what’s happening to our GBN though. Calvin didn’t mince his words calling out his bosses did he? I think the writing’s on the wall now. WTF did Fox start? Like a house of cards tumbling down.😬

There’ll be some that say Fox is controlled opposition as a result. How can this man just let loose with his tongue and have no conception of the eggshells GBN are walking on? Katie Hopkins’ analysis of what was going to happen as a result was bang on: see how various articles are appearing for GB News to be shut down. She said this would happen. Wait until Piers Morgan gets stuck in if he hasn’t already. At least Neil Oliver is careful and precise with what he says without saying what he is not allowed to say. WTF!! Blimey, we really are in a reality show called Big Brother. It’s only a matter of time before eyes swivel this way and they start accusing us of being right-wing white supremacist anti-trans anti-vaxxer bigots!

Oh eyes have been on us lot a long time.👀 You can tell by the amount of dangleberry-munching ‘pilot fish’ some of us attract, like winnets on a sheep’s arse following us round continually, that we’re on a short list.🤭 Or maybe that should be ‘hit list’. 🤔 Let’s just say that if that’s their attempt at a PsyOp then they’re obviously lacking in more than the one department.🐹

“You can tell by the amount of dangleberry-munching ‘pilot fish’ some of us attract, like winnets on a sheep’s arse following us round continually, that we’re on a short list.🤭”

Poetry Mogs. Poetry.

😘

Well I did mention growing up one of my inspirations was Roy Chubby Brown.😇😁 I think he must’ve made a lasting impression…With a big ole side helping of the Viz, of course. 🙈

Good old Chubby. I saw him live once – incredible. Actually I was watching some YouTube clips last night. The yanks love him.

I do.

If you look at the prevalence and distribution of illnesses in the statistics for new claims for disability benefits you will see some interesting data. A five fold increase in haemorrhagic diseases. I can’t imagine what might’ve caused that. If you look at the trajectory of our civilisation it is hard not to conclude that most of us will be on the dole and demoralised or in agony or dead in the not too distant future. Of course such a society can’t survive.Ted Kaczynski talked about the dangers of carrying on along this path. He called it technological slavery. His manifesto speaks to our times. A Kaczynski scholar remarked that one of the evils of technology is that it so insinuates itself into your life that it makes you feel reluctant to criticise it, or if you do criticise it then to do so in a qualified and reserved way, which I thought was quite an astute observation.

How about talking about what got us into lockdowns…

Neil Ferguson et al’s Imperial College Report 9, published in March 2020.

This report recommended suppression of ‘the virus’ “until a vaccine becomes available”.

It wasn’t disclosed in the report that Ferguson is funded by arguably the world’s biggest vaccine pusher, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

This report recommended impeding the free movement and association of people until a vaccine was available, and was apparently adopted unquestioned by the then Boris Johnson government, and influenced policy around the world, including in the US, and in Australia, where I live.

It’s incredible the influence that Neil Ferguson et al have had on the lives of billions of people, these ‘modellers’ – how on earth could this happen?

This all has to be examined now, go back to early 2020 and beyond, and investigate how a highly lucrative global mass population ‘vaccine solution’ was put in place against a disease it was known from the beginning wasn’t a serious threat to most people?

How could this happen after the obvious Swine Flu H1N1 scam in 2009?

Re the 2009 flu scam, see for example WHO and the pandemic flu “conspiracies” published in The BMJ in 2010.

It’s bewildering that The BMJ went along so wholeheartedly with the Covid fraud, when it reported on the 2009 debacle.

How could this happen again?

And recently…this announcement…

Guess who was involved in peer review of this report…Neil Ferguson.

You could not make this stuff up.

We are way passed the vacuous “lessons will be learned.” We need to deal with where we are now. This completes the picture:

https://www.technocracy.news/technocracy-sustainable-is-the-new-code-word-for-genocide/

It’s all rather shocking isn’t it…

The treachery of ‘our own governments’.

Betraying the people.

When are we going to get accountability for these crimes?

Have to identify the specific perpetrators of specific crimes, and bring them to account.

There’s a legal system there somewhere isn’t there, to do this task?

How do we get it activated?

This is interesting…

How BlackRock Conquered the World

The situation was there before the lockdown by two months. If you actually look at the economic data the global economy was about to crash which would’ve been far more abrupt. The lockdown was a ‘hush hush wink wink’ moment to quietly try and reconfigure things so that the masses didn’t get too upset and to also create the most profitable remedy imaginable using dubious technology.. I thought this was obvious to everyone. You can easily look it up. It is very easy to point fingers but there was much more to it than that. It wasn’t them and us it was shared guilt in a collective delusion. This wasn’t even hidden. If you are labouring under an illusion them maybe you are slave to the mind control forces that they exerted upon you. But then be aware of your own shortcomings.That disease was called ‘vaping illness’ and oddly enough most of the cases in 2019 were centred around Fort Detrick.

You have to have total recall of the spirit of the times. If you have that then good on you. Because you really have to understand it. It might’ve been a mood for us but remember that earlier that year, in January, Trump assassinated General Suleimani of Iran in broad daylight. A small incident in the West but I think a big incident in terms of the cosmic fabric.

I don’t mean to preach but you just can’t go on like this as a country worshipping money and nothing else. You will end up with no money and no culture honestly. You have to find a way to move away from money worship. I know that it is difficult once it has taken hold but there is no other choice if you wish to survive.

Covid/lockdowns were not the cause of our fiscal malaise, they were to hide it by presenting a plausible scenario of how we got here. The money (850BN of it) had already been printed to kick the – already happening – financial collapse down the road. But this is only the collapse of the fiat debt system. We don’t need to take part in the impending collision, we just need to step aside. The moneymakers, be they aristocrats, industrialists, bankers or technocrats will destroy each other while fighting to retain power and blaming everybody else for the mess they got themselves (and us if we don’t step aside) into.

“[It] suits every political party not to talk about the longer-term spending trajectory Covid has set us on.”

Er no, all to do with the stupidity of government policy. We had a perfectly good tried and tested pandemic preparedness plan that was jettisoned so we could all panic and run around like headless chickens. That’s of course if you believe there was a pandemic in the first place.