“The true effectiveness of the first booster was short-lived, if meaningful at all. Peak protection was somewhere between mediocre and zero, and it is impossible to narrow that range.”

That was my conclusion after analysing the effectiveness of the first booster (reposted on Brownstone and Daily Sceptic).

We can try to narrow the range by analysing the merit of another booster, the fourth dose, as compared with three previous doses. I will show here that its effectiveness was close to zero, with an upper bound around 15%. Whether it was exactly zero, 5% or 15% makes no difference. That’s not a basis for mass vaccination.

My analysis of the first booster was based on removing one of two key biases, which is called the healthy vaccinee bias. That strong bias results from the fact that people who take a vaccine (whether against flu or against Covid) are healthier, on average, than people who do not, even in narrow age bands, and even among residents of nursing homes. Therefore part, or all, of their lower Covid mortality is not the vaccine effect. They are simply healthier people than their unvaccinated counterparts.

To remove the healthy vaccinee bias, we adjust the risk of Covid death in vaccinated people upwards, using data on non-Covid death, and thereby create two groups that are comparable on their baseline risk of death. (Mathematically, it is equivalent to a downward adjustment of the Covid death risk in the unvaccinated.)

The method is not perfect, but it does get us much closer to the truth than naïve comparisons of vaccinated with unvaccinated, which have been presented on countless dashboards. Moreover, in the absence of randomised trials of the mortality endpoint, that method is likely superior to observational studies that try to adjust for, or match on, a limited number of health-related variables. Such adjustments proved unsatisfactory in the case of flu vaccines and recently in the case of the first booster.

My largest source for the first booster (third dose) analysis was the dataset of the Office for National Statistics (ONS), England. I used it again to study the effectiveness of the second booster (fourth dose).

Contrary to what some might think, the healthy vaccinee bias is not restricted to a comparison of vaccinated (two doses) with unvaccinated. Three-dose recipients were healthier than two-dose recipients (consistently), and that was the case again with recipients of the fourth dose. They were healthier than three-dose recipients. Their non-Covid mortality was substantially lower in every age group and every month I analysed, with only one exception.

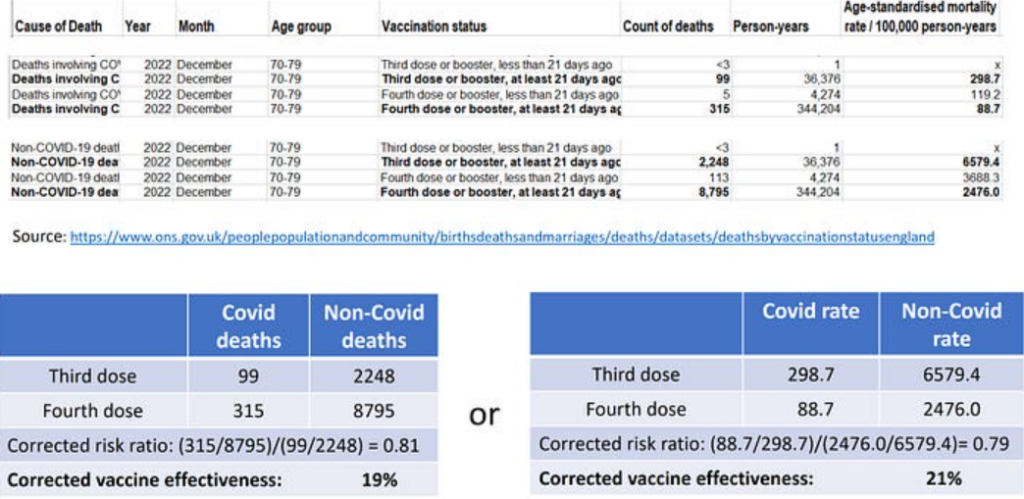

The example below shows the healthy vaccinee bias in the ONS data — in one age group (70-79) and one month (December 2022). As you can see, the rate of non-Covid death in four-dose recipients (2,476.0) was less than half that rate in three-dose recipients (6,579.4). Of course, the second booster was not expected to protect from other causes of death. That’s the evidence of the healthy vaccinee bias.

In the tables below the data, I show two corrected estimates of effectiveness. The count-based estimate (left table) is not prone to miscalculation of person-years, which occasionally happened in the ONS data. It will be used throughout. (I will skip a technical explanation of the computation.)

The biased estimate of effectiveness is 70% (1 – 88.7/298.7). After correction we get mediocre effectiveness of the fourth dose (about 20%), which may still be an overestimation due to another key bias called differential misclassification of the cause of death.

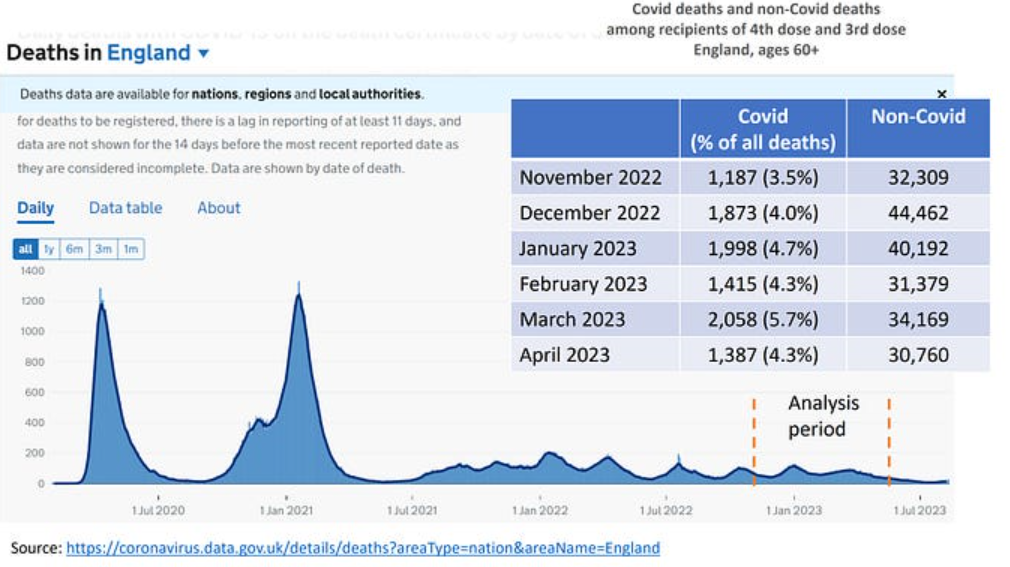

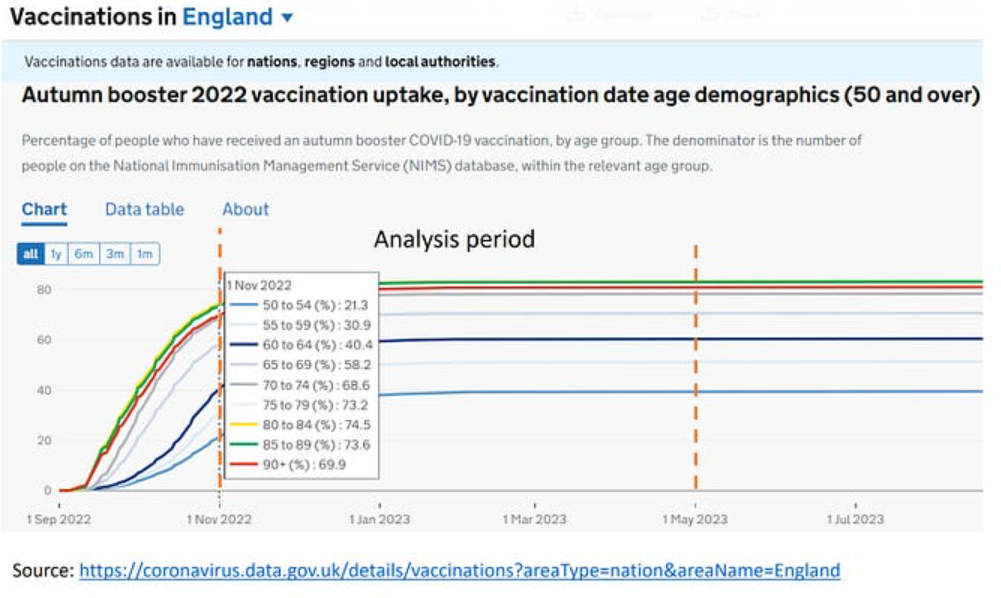

My recent analysis of the first booster effectiveness in the ONS data was confined to age 60 and above over a six-month period: November 2021 through April 2022. I will examine the second booster effectiveness in the same months a year later: November 2022 through April 2023. That period contained two small (endemic) Covid waves in England (top figure). The booster uptake is also shown (bottom figure.)

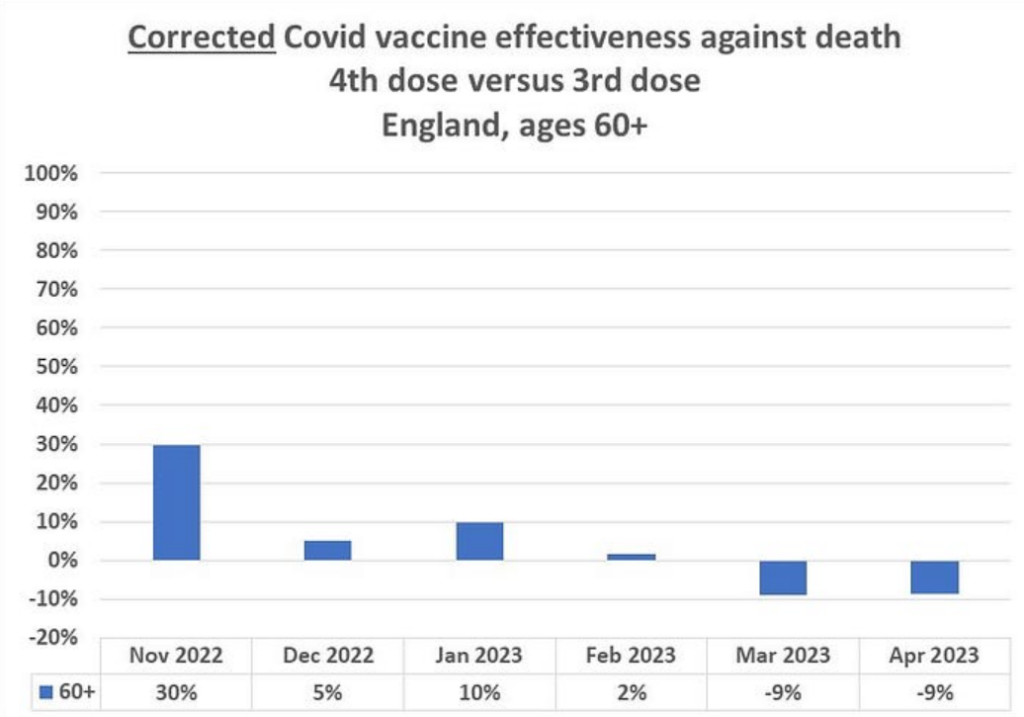

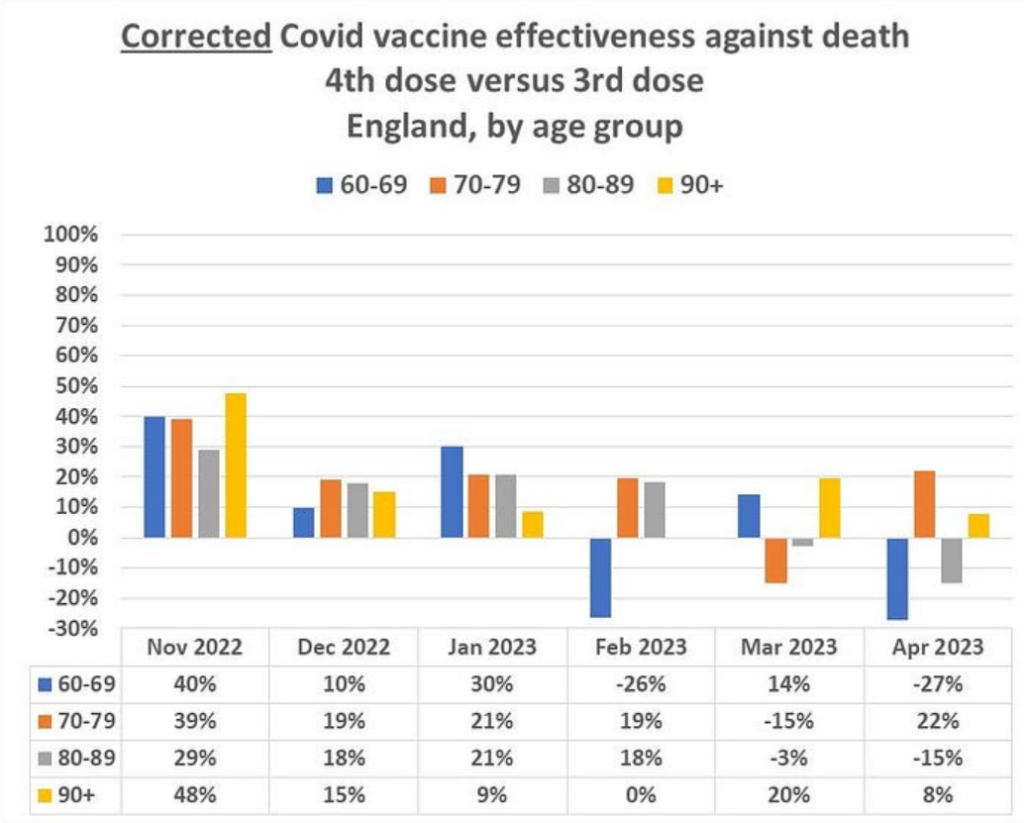

The spread of the corrected, monthly estimates (graph below) is compatible with near zero effectiveness of the second booster. Deviations in either direction should not be over-interpreted. That’s the expected (random) spread of results when the true effectiveness is somewhere near null. The aberrant result in November 2022 might reflect some other bias that is related to the rapid rise of vaccine uptake. There is no other plausible explanation.

Monthly estimates in four age groups are shown in the graph below. By and large, we observe the same near-null spread in each age group, and the same divergence in November 2022.

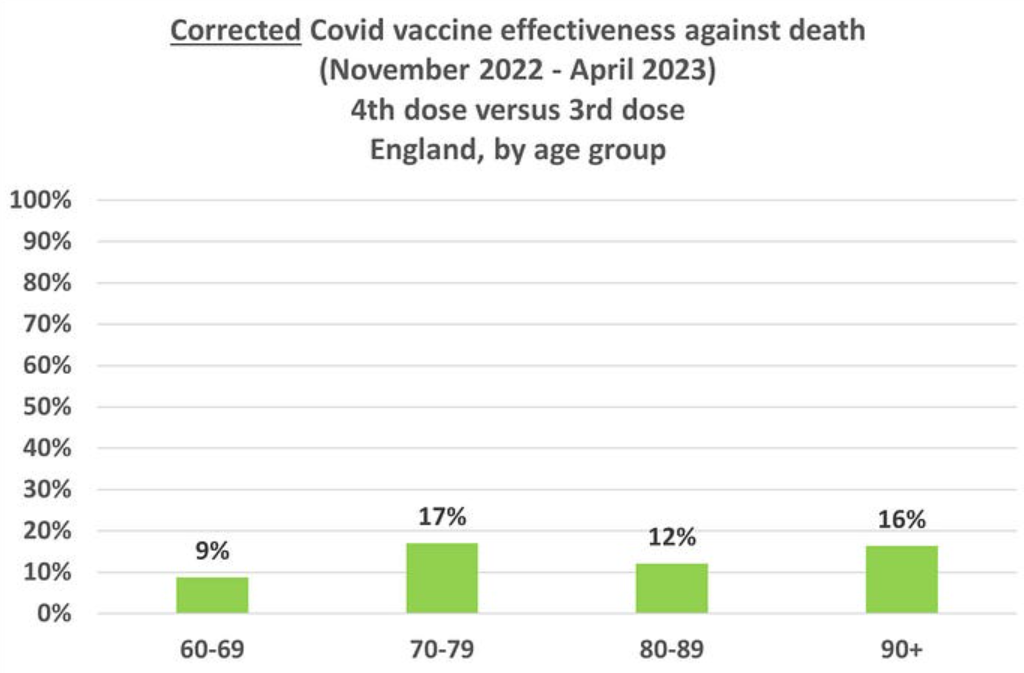

On the assumption of random fluctuation over time — around some nearly stable, small value — we may combine the six-month data for each age group to get a single estimate. (Those with advanced statistical knowledge might be familiar with the bias-variance tradeoff.) As shown below, effectiveness is estimated to be 10-15% or so, assuming complete removal of the healthy vaccinee bias and no other bias. Neither is necessarily true.

As I explained elsewhere, another key bias — differential misclassification of the cause of death — would drive above-zero estimates even closer to zero. Unfortunately, it cannot be easily removed.

In short, a useless, or nearly useless, booster.

In March 2022, Time magazine reported on the upcoming second booster, under the headline ‘What to Know about a Fourth COVID-19 Vaccine Dose‘. A reporter wrote:

On March 29th, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued an emergency use authorisation (EUA) for a fourth dose of Pfizer-BioNTech’s and Moderna’s mRNA vaccines for people 50 and older.

“The FDA believes this option will help to save lives and prevent severe outcomes among the highest risk patients,” said Dr. Peter Marks, director of the FDA Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, in a briefing on March 29th [2022].

The belief was based on “an analysis of emerging data”, which meant pilot work — not a randomised trial with a mortality endpoint. That may be the basis for compassionate use of an experimental drug in a patient, but not for mass vaccination, especially when there are short-term vaccine fatalities and serious adverse effects. To those we should add unknown long-term morbidity and mortality consequences of self-manufactured spike protein and exogenous lipid nanoparticles (the mRNA carriers) in various tissues. No, the vaccine does not remain and degrade at the injection site, as originally promised.

It may very well be that adverse consequences of repeated Covid boosters will vastly exceed temporary small benefits (if any). ‘Safe and effective’ they are not. They should not be allowed until meaningful effectiveness against death is shown in a randomised trial (with informed consent).

Dr. Eyal Shahar is Professor Emeritus of Public Health at the University of Arizona. This article first appeared on Medium.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

”Therefore part, or all, of their lower Covid mortality is not the vaccine effect. They are simply healthier people than their unvaccinated counterparts.”

Is this the same author that mentions this ”healthy vaccinee bias” in every single article? I’m not sure if he reads these comments or that I’m just failing to grasp something but I seriously cannot and will not accept that all of the jabbed people are healthier than all of the never-jabbed people. You do not have to look far to find the data ( or that from our own personal experiences, being surrounded by constantly ill jabberwockies! ) which supports this either because it’s basically what the excess deaths are, it’s what the increase in cancers are, it’s the increases in disability and going off sick from work, it’s the increases in sudden deaths and myocarditis in kids/youngsters.

Perhaps somebody needs to explain this to me with the aid of an etch-a-sketch but I totally do not accept the above statement. The only healthy people are the ones that haven’t screwed up their immune systems or who don’t have heart damage because they didn’t get the vax.

Effectiveness of the 4th dose against death was around zero – so, same as the effectiveness against death of the 1st, 2nd and 3rd dose? Just basing this on what my own eyes observed, an increase in excess death in 2021, excess death 2022 equal to that of 2022.

Now do the effectiveness of any dose of this poison causing death – presumably very far from zero.

It really is effective, we’ve just been looking at what the effect was supposed to be all wrong.

Just waiting for the science to scream about the effectiveness of lobotomies, beheadings and death camps. 100% safely effective. Line up.

The excess deaths seen since mid 2021 are mainly non covid deaths so don’t tell us anything about vaccine effectiveness. I think there’s been enough analysis of the data by qualified people who are sceptical of the “safe and effective” mantra to show that 2 doses lowered the risk of dying from covid for about 6 months. Given the number of vaccine related deaths and serious long term side effects whether or not it was beneficial to people at higher risk of covid death to be vaccinated is harder to work out. Obviously this doesn’t justify mass vaccination of younger age groups or the lack of information given to people meaning they couldn’t make an informed choice.

Great analysis, thanks.

Add in the Dead and Injured and we have negative ‘efficacy’.

I don’t remember the propaganda mentioning that.

And, that is just the beginning. ADE is real, and pouring neurotoxins into your body is unlikely to be healthy (see cocaine or rat poison for more info).

I’m not sure about the healthy vaccine effect either Mogs. I think a lot of people who care about their health new they were at no risk from covid and looked into the injections and thought not a chance. Also consider how desperate they were to stuff it into everybody starting with the people on deaths door, but they all popped off within the 1st 2 weeks so were considered unvaccinated. I’m guessing people who had an adverse event with their 1st two stopped taking them because they became unhealthy and so on with subsequent boosters so the only people left are the ‘healthy’ because they haven’t had an adverse event (yet). Three hundred thousand more people are claiming disability since the start of the roll out which gives you an idea of the unhealthy vaccine effect.

On a different note, I wonder now Russel Brand is in the process of being cancelled when are sites like the DS and TCW going to be removed from the Internet surely it can’t be long now. At that point will Toby still consider it to be all a cock up. I think the net is starting to tighten.

Well just to generalize things a little more here, talking about all other vaccines here. You’ll remember Dr Paul Thomas in the US, the one who had the peer-reviewed study which showed unvaccinated kids were healthier than vaccinated across the board and that study was retracted. Here he is in a 6min clip of a presentation and what’s interesting is he’s including adults. For example; zero cancer in unvaccinated adults vs their vaxxed counterparts. It’s like the Amish isn’t it? So how does this ‘healthy vaccinee bias’ apply to the Amish then? They’re naturally free of many chronic diseases, things like autism/ADHD don’t apply, are they starting at some disadvantaged position to their vaxxed counterparts? The data do not support that. On the contrary, the data show it’s the vaccinated that have these diseases/disorders just like it’s the vaxxed babies dying of ‘SIDS’. We are the control group and it’s not us filling up the hospitals in winter or dying suddenly decades before our time, and yet…”…they are simply healthier people than their unvaccinated counterparts.” That seems an outright false statement to me and contradicted left, right and centre with actual evidence.

https://odysee.com/@AussieFighter:8/Stunning-Dr.-Paul-Thomas-Blows-Up-The-Conventional-Vaccine-Narrative:2

N.B Here is his website, which I think is clearer when looking at the data and graphs;

https://www.doctorsandscience.com/presentations.html

I’m one of them. At the start of the campaign, I more or less said “no thanks, I’ll wait and see.” As it happened, the more I see, the less I like about it. Incidentally, my local surgery hasn’t bothered me about it, and has not tried any more to flog it to me. Not sure if that’s generally the case.

https://www.globalresearch.ca/g20-announces-plan-impose-digital-currencies-ids-worldwide/5832785

Absolutely hux’s that is what all this is about a digital prison or digital slavery take your pick. I wonder if Billy boy will pay us reparations.

https://open.substack.com/pub/igorchudov/p/bill-gates-and-the-wef-push-biometrics?r=1omj4z&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=email

Roll up, roll up, the NHS is fast tracking your 17th booster this week for a COVID variant with so many mutations and that is so mild that the prick in your arm will have even less benefit – but all of the dangers – of your previous 16 boosters.