When you give cash to homeless people, do they just waste it on alcohol, drugs and cigarettes? No, according to a new study that’s been covered favourably in Vox, the Washington Post and several other outlets. Yet there’s more to the study than its headline finding.

Ryan Dwyer and colleagues carried out an experiment in which 50 homeless people were randomly assigned to receive an unconditional cash transfer of 7,500 Canadian dollars. Another 65 homeless people served as controls. The two groups were then followed for a year to gauge the impact of the cash transfer.

As is increasingly common in social science, the researchers preregistered their analyses. What does this mean? Before collecting any data, they published a document online describing the analyses they intended to carry out. The rationale for preregistration is to demonstrate that any significant results you report were not found through p-hacking (running and then rerunning the analysis until you find a significant result).

Dwyer and colleagues preregistered the following hypothesis: “Participants who receive cash transfers will demonstrate better outcomes than those who do not receive cash transfers”, with “better outcomes” referring to improvements on measures of cognitive functioning and subjective well-being. (Participants’ “assets and spending” were only measured as a “supplemental outcome” for “exploratory analysis”.)

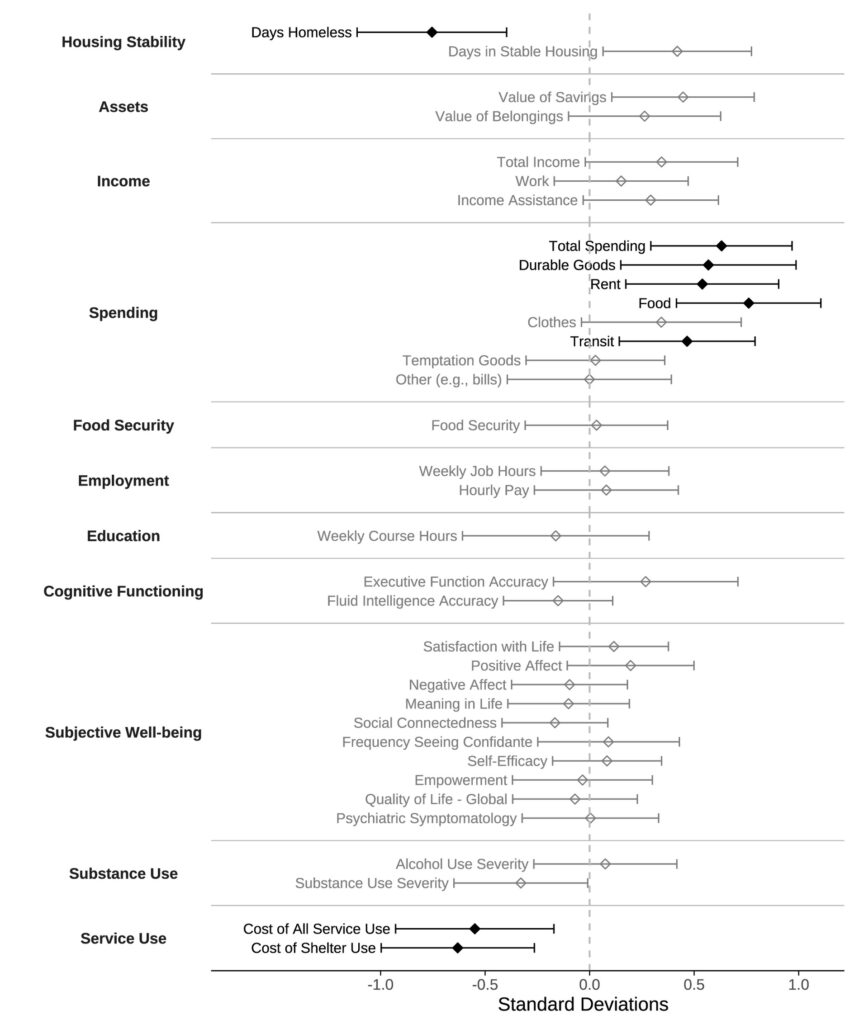

So what did the researchers find? When it came to their preregistered hypothesis, there was no evidence the cash transfer had any impact. This is shown in the chart below. Those who received the cash transfer did not score significantly better than the controls on any of the measures of cognitive functioning or subjective well-being. (The chart shows results at the one year follow-up. But the differences were also non-significant at the one month follow-up.)

Where the researchers did find significant differences were in number of days homeless and spending on food, rent and durable goods. Here, those who received the cash transfer fared better than the controls. And as you can see, there was no significant difference in spending on “temptation goods” (alcohol, drugs and cigarettes).

In summary, the preregistered hypothesis was not supported – though the cash transfer recipients did fare better with respect to spending and number of days homeless.

Lack of support for the preregistered hypothesis was reported as the study’s finding, right? Wrong. It wasn’t even mentioned in the abstract (as noted by Jon Baron, President of the Coalition for Evidence-Based Policy). Instead, the study’s findings were portrayed as “unambiguously positive”.

And even the more encouraging results are somewhat suspect. There was substantial attrition in both groups (meaning that some participants dropped out of the study after randomisation). So we can’t be sure that the differences in spending and number of days homeless were actually caused by the cash transfer – rather than by selective drop-out.

What’s more, the absence of a difference in spending on “temptation goods” may be partly attributable to the fact that homeless people with “severe” substance abuse problems were exempt from participation.

While Dwyer and colleagues’ study does offer preliminary evidence that unconditional cash transfers help homeless people to get back on their feet, the findings were presented in a rather misleading way. Just reading the abstract of a scientific paper can be a useful time-saver, but it’s always good to check the main results yourself.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Here’s an idea. Perhaps they should try building trust by NOT LYING.

What an old fashioned idea.

Radical even

It’s not just lying, it’s the whole style and attitude of news presentation that turns people off. I’m old enough to remember when there was only one TV channel – the BBC. The newsreader I best recall was Richard Baker and when I say newsREADER, I mean exactly that.

He sat behind a desk, visible from the midriff up, read from a script, didn’t move his hands except to turn over a page, didn’t move his head, smile, emote or try to amuse. He didn’t get out of his seat and prance round the set, wave his arms, point to graphics, or show off. Baker simply stated facts about who, what, where, when and how.

It was impossible to detect Baker’s personal political leanings, if any. If there was bias in the script, it was very subtle and no adult shouted ‘Bull****!’ or switched off in disgust, as happens all too often these days in many households, including mine.

Take Whatsisname on ITVX News for example (I don’t watch live TV or the BBC anymore). He couldn’t deliver the news in a straightforward, matter-of-fact way if he tried. It’s more of a biased political lecture-cum-body language performance, revealing his predictable politics in every eye-widening, eyebrow-twitching, forehead-wrinkling, lip-curling, head-slanting, hand-waving gesture.

And if the face, head and body didn’t give it away, the voice in its pitch, tone and emphasis certainly would: righteous indignation, sneering incredulity, sarcasm disguised as humour. We know for certain that he hates Nigel Farage and he doesn’t care who knows it, either.

It’s no surprise that we increasingly switch off mainstream TV ‘news’ – except to the broadcasters themselves, apparently. I detected their incredulity as they reported the year-on-year reduction in viewing figures.

By doing a bit of ‘off-grid’ research and reading, then evaluating and concluding, one is left with nothing but scorn for the MSM. GB News is regrettably getting more woke by the day, but it still beats Sky, the BEEB, Ch4 and ITV by a country mile. None of which I’ve watched for three years. (Unjabbed 75 yr old).

Acquaintances are usually shocked when they tell me a piece of ‘news’ and I admit I have not heard anything of the subject in question.

“It’s on the BBC.”

I don’t bother with the BBC.

“Oh.” And you can hear disbelief in their voice.

Actually, substitute any MSM outlet, it’s not just BBC.

As you say 10, why would we bother with MSM when there are hundreds of reliable, honest news sites available with a bit of searching and frequently good DS people posting interesting links anyway.

MSM outlets are like comics – ok for an occasional browse when nothing else is available.

Even Peter Hitchens says watching BBC is like Pravda.

Why “even” Peter Hitchens? What on earth do you mean?

You are quite right, I should’ve dropped the ‘even’.

Couldn’t agree more. I haven’t looked at MSM news for several years. It shocks people when they bring up the latest propaganda piece and lies from it. Such as this morning. A friend told me something about an e coli scare ‘on the news’ and supermarkets are emptying their shelves of sandwiches and other snack stuff etc.

Huh said I and explained my scepticism of anything spouted by ‘them’.

He seemed a bit dumbfounded at first then found himself agreeing with me.

Impossible to distinguish the truth (if there is any) from the absolute BS continuously spouted as I recall.

You are right about GBV News. Can’t stand their sycophantic obsession with the Royals, they are on Channel Five level for that one. The real truth talkers, or people who are not scared to talk controversial issues are gone or downgraded. Leo on Saturday night is good but clashes with other things and they don’t repeat that show later. Headliners is OK with Lewis ‘Team World’. Just call them Globalists, what is he scared of.

Bad Cattutude on the Climate Grift propping up the failing MSM with generous funding.

https://boriquagato.substack.com/p/climate-catastrophism-as-big-business.

Once you see it, you can’t unsee it.

Yet they imply it’s our stupidity that’s made us leave.

I listened to the propaganda channel (BBC World) on the radio in the small hours, and they broadcast that story. The reader sounded quite surprised, but I thought there wasn’t anything surprising, given how they behaved over the last few years!

But let’s be honest, it’s not because masses of people have woken up to the mendacity of the MSM or Labour wouldn’t be walking into No10.

Many people, like me, use mainstream media just to see what “the establishment” view is of world events which is normally just lies and propaganda.

We then ignore it and rely on “trusted” alternative media sites which have a much better unbiased understanding of world affairs.

I was a Guardian buyer for 35 years until 10 years ago when they changed, and we parted company due to their lies and propaganda.

The Guardian, BBC, Telegraph, Mail, Murdoch etc. etc. etc. would all do the peace-loving world a favour if they all went to the wall and were replaced by small independents.

There are so many alternative media sites which are better than the MSM and it is these that many people are turning to.

And here’s some ‘not on the BBC’ news.

Kathy Gyngell waxing lyrical about Farage’s speech at Frinton. I know links have been posted previously. Link embedded.

https://www.conservativewoman.co.uk/farage-shines-in-frinton/

And here is another fine article that won’t be found in the MSM.

https://www.conservativewoman.co.uk/why-we-need-borders-and-must-quit-the-echr/

“If we are to solve the immigration crisis, we must assert the superiority of the Common Law and withdraw from the ECHR. To those who object that this will make us an ‘international pariah’ we can

offer the unanswerable reply: so what?”

I believe Jabbit is quite a believer in the ‘so what’ response.

Gave up on the news years ago. Junked our TV 20 years back for starters, haven’t listened to the news on the radio of years, and we don’t buy newspapers. Scan the headlines on line – The Guardian to see what hysterical nonsense they are propagating – but only rarely actually read an article.

No smartphone (too smart to have one) means also that I am not permanently online; to go one line I have to go upstairs… so I spent little time online

If people fall for this again they deserve everything coming!

Ex-health chief predicts cause of next pandemic with 50% death rate as infected wiped out (msn.com)

“You’ve had the pandemic …”

No, Mr Newman. YOU and people like you might have had a “pandemic” but the rest of the world didn’t. And more and more people are starting to ignore people like you because they’re starting to smell a rat.

This is hardly surprising though is it? People now demonstrably have trust issues with various things; politicians ( as evidenced by the polls and what’s happening across Europe and the U.S ), Big Pharma ( it’s often reported there’s been a downturn in people rocking up for childhood vaccinations and the Covid booster uptake has been in decline for some time ), and a distrust of MSM is naturally going to follow, because who has been the biggest, most influential mouthpiece when it comes to spreading government/globalist propaganda and lies? The media. There’s a definite lag effect when it comes to the reporting but this just confirms what is happening in real life, and I wouldn’t expect anything else, actually.

Much like if you find out your other half has been having an affair with your best friend, would you really continue to vote for a party that continues to let you down, election after election, never keeps their promises and lies to your face? What intelligent person is going to just stay in such a toxic relationship like a right mug and not break free from the whole dysfunctional cycle? Any right-minded person would ditch their partner ( and their bestie ) just like they’d go vote for some totally different party/person for the first time in their lives. People don’t have to stay put and continue to be shat on from a high height like they’ve no control over the matter. So why anyone would even bother with MSM nowadays is beyond me. It’s just insane, but I think we know by now the correlation between MSM muppets and the following of the various government agendas. The cultists need to step away from the Kool-Aid and detox their minds.

They should do a survey at the next ‘protest’ or when the ‘Just Sod Off’ idiots are next glued to the road and ask them if they’ve got a BBC license or if they read the papers. Surely the results would be entirely predictable.

Nice one Mogs

I cancelled my TV licence during Covid as I didn’t see why I should pay to be bombarded with lies.

I did too!

No …. I expect they’re turning to the alternative sources of news to the mainstream propaganda outfits, like the BBC, Sky and C4.

After a while even Sheeples realise they are being lied to. I doubt they’ll be quick enough on the uptake to not vote Kiernocchio and Foul Mouthed Thief into power though. I figure by Christmas they’ll have figured it out.

Since I’ve been ill, The 17 year old son of a neighbor has been cutting my grass for me. Like many of his generation, he gets his news from social media. he tells me that in the last couple of weeks Farage has been all over it and is very popular. So Starmer might regret lowering voting age to 16

I don’t think people are less interested in “The News” just fed up with being lied to by the MSM. “The News” has become like “The Science” a load of untrustworthy propaganda. Be interesting to know how many people have switched to more reliable news sources away from MSM like TDS and U.K. Column to get their news. I’m assuming the survey or whatever ever it was just asked whether people still read or watched the MSM in their country?

“No wonder the U.K.’s current election campaign has barely lit anyone’s fire”.

The election hasn’t “lit anyone’s fire” because the uniparty have nothing newsworthy to say, just the same boring BS. Farage is not given the airtime needed to provide an alternative view.

The BBC just can’t help themselves! depressing, relentless and boring” is the least of their worries. They should try being truthful, non-woke and not pretending they are the arbiters of what can be said.

How bad the situation is for the legacy media which have serves as the establishment’s mouthpiece for ages is vividly described by Ted Gioia in his substack The Honest Broker (december 6, 2023 post “In 2024, the tension between macroculture and microculture will turn into war”). The establishment’s drive towards online censorship is partly explained by the wish to keep their controlled narrative machine functioning by cracking down on the new lethal competition.

I avoid the news because it’s so damn depressing. And I only believe half of it anyway. Or maybe less.