Cambridge University, in responding to an FOI request, confirmed on September 7th that “No specific date has yet been determined for a handover” of its Benin Bronzes to Nigeria.

Daily Sceptic readers may recall that on May 16th Cambridge’s Museum of Archaeology & Anthropology (MAA) was due to hand over 116 valuable Benin artefacts to Nigeria’s Museums Commission (NCMM), but postponed just days beforehand. Nor does the transfer now seem likely to happen in October, as anticipated.

Artworks certifiably seized from Benin by a British expedition in 1897 were due to be returned to their ‘rightful owners’, with much backslapping all around. When Digital Benin went online last November, illustrating 5,246 historic Benin objects in the world’s museums, the British Museum’s collection topped the list with 944 pieces, and the MAA came fourth with 350 – though many of those are undistinguished items of wood, clay or leather. When I visited last December and took the photo above, an attendant confided, “The Nigerians have already been here and chosen the things they want”, and the 116 items on Nigeria’s wish list, just provided under FOI, appears to be the result.

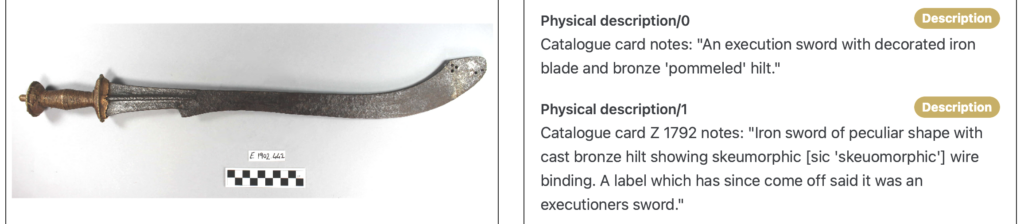

Item 48 is a 64 cm sword, uncontroversially described as a “Ceremonial sword with decorated iron blade and bronze ‘pommelled’ hilt”. But this same sword is also illustrated on Digital Benin, with details supplied by the University in July 2022: “Catalogue card Z 1792 notes: An execution sword with decorated iron blade and bronze ‘pommeled’ hilt” and “Iron sword of peculiar shape with cast bronze hilt showing skeuomorphic wire binding. A label which has since come off said it was an executioner’s sword.” [my emphasis]

For twelve decades the museum knew it as an “executioner’s sword” but suddenly it’s thought to be – less disturbingly – merely “ceremonial”. Alright, if you must; but see below for what the ceremonies involved. This isn’t the only odd thing about MAA’s ‘Provenance Notes’ in its handover list.

Most of the first 80 items were bought from or donated by the dealer William Webster, who was known to have handled bronzes sourced from the 1897 Expedition. He may well also have owned ones that came from Benin before or after that date and, as a canny dealer, may have let buyers believe every piece he offered had the ‘1897’ prestige – not something that seems to have occurred to the University, which largely relies on its catch-all claim “The Benin City artefacts sold or gifted by Webster were taken during the 1897 Benin Expedition” as provenance.

Thirty-one of the first 80 were bought from J.C. Stevens Auctions, most likely at a 1902 sale. After item 81, the Cambridge curators apparently threw caution to the winds, resorting to provenance statements such as “Possibly donated by… this association suggests that…” and “Given… likely sale room or auction acquisition, this is presumed…” and “Given the stylistic affinities… it is presumed that…”. The word “presumed” appears in the provenance field for 24 of the list’s last 36 pieces.

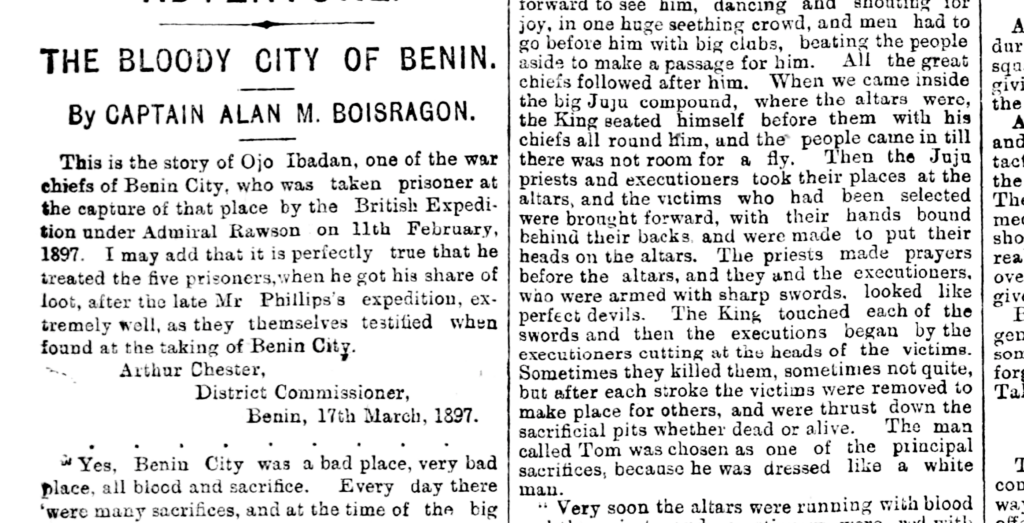

You couldn’t hang a dog with evidence as tenuous as this, and nor should you hand over ancient artefacts potentially worth millions of pounds, let alone their shared value to humanity as uniquely skilled art from the West Africa of half a millennium ago. The known record for a Benin ‘bronze’ head (actually brass) was a private sale for £10 million, and there are nine bronze heads in the MAA’s list, plus many significant ivory and brass works. In an open market, with auction houses free to sell, this haul of 116 items would surely fetch many tens of millions. On Valentine’s Day 1899, the South Wales Echo printed an extraordinary report of the last days of Oba Ovonramwen’s reign in Benin, before he was deposed by the 1897 Expedition. Ojo Ibadan was one of the Oba’s war chiefs, though himself of Yoruba descent and not an Edo, and had led the massacre of the unarmed January 1897 Expedition. [What follows is revolting; stop here, gentle reader, if you’re easily shocked.] On March 17th 1897, Arthur Chester, Benin’s newly-installed District Commissioner, recorded Ibadan’s testimony. The following are excerpts:

Yes, Benin City was a bad place, very bad place, all blood and sacrifice. Every day there were many sacrifices, and at the time of the big Customs it was blood, blood, blood, all day long. I do not say it was the fault of the King [Oba]. He was only King by favour of the Juju councillors, and had to do what they told him. If he did not, then, I think, he would have been sacrificed also, and there would have been another big Custom. [The British understood this, and only exiled the Oba with a small retinue of wives and children, though several of his most guilty chiefs were tried and executed.]

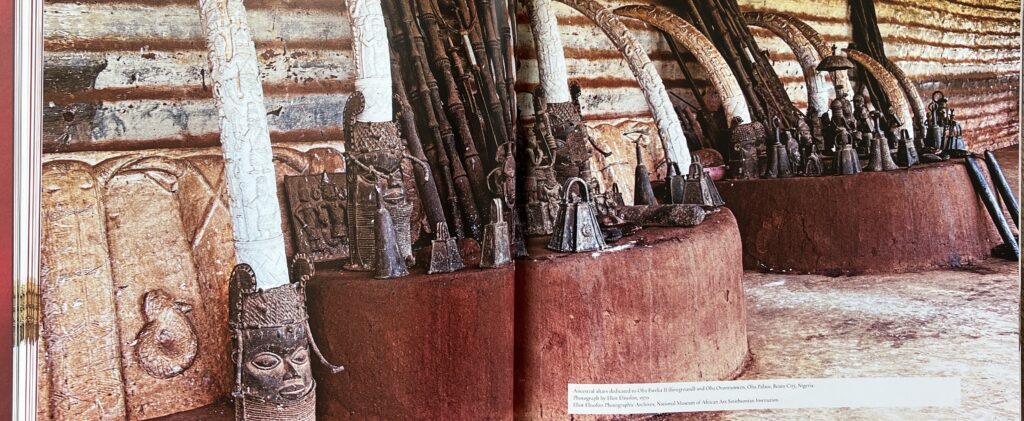

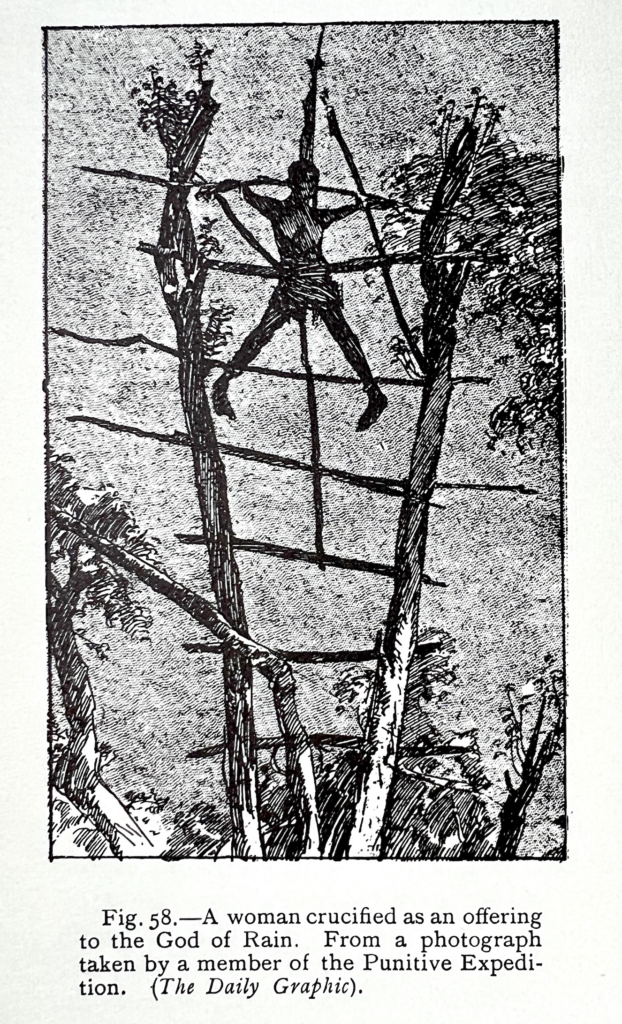

Now it is the custom in Benin after an expedition for the prisoners to be portioned out: To the King so many, to the councillors so many, to the chiefs so many; and these slaves are to be kept to the next Custom when sacrifices are wanted. As the [Benin, not Western calendar] New Year approached the people began preparing for the Custom of the anniversary of the King’s father’s death. So many slaves were told off to be sacrificed at the altars, so many for the sacrificial pits, of which each family possessed one at least; so many, and these were women, for crucifixion on the sacrificial trees.

Just as the New Year began, and all was being prepared for the Custom, there came a report that the white men were coming with a big expedition. Then it was said that they were bringing no soldiers, only many, many carriers. My company of soldiers were ordered to go and stop them.

Ibadan’s ambush of the expedition succeeded; eight white men were killed, though two escaped, badly wounded, and survived to tell the story – the result was to be February’s Punitive Expedition:

My soldiers had killed or taken prisoner nearly all the white men’s followers. The road was like a river of blood, and all along it there were the dead, headless bodies of the men that my soldiers had killed. All the white men were dead [or so Ibadan believed], and of the black men, we took to Benin City eighty heads and one hundred and thirty prisoners. After this I was given five prisoners as slaves and five more to be kept for the big Custom.

Three days after we came back, began the big Custom which lasted a fortnight, and during which time the King showed himself thrice to the people, as he went to the sacrificial altars when the most important of the sacrifices took place. On these days he wore his King’s dress, which was so covered with coral and beads that he could scarcely walk.

It was blood, blood, blood all over the city till we could see and smell nothing but blood. All through the night, one heard the sound of the big war drum, on which the skin of a man was stretched, talking to the people and saying that now was the time of sacrifice. At early morning all the other drums began to talk, until it was time for the King’s procession to the altars. All the great chiefs followed after him. When we came inside the big Juju compound where the altars were, the King seated himself before them with big chiefs all round him, and the people came in till there was not room for a fly.

Then the Juju priests and executioners took their places at the altars, and the victims who had been selected were brought forward, with their hands bound behind their backs, and were made to put their heads on the altars. The priests made prayers before the altars, and they and the executioners, who were armed with sharp swords, looked like perfect devils. The King touched each of the swords and then the executions began by the executioners cutting at the heads of the victims. Sometimes they killed them, sometimes not quite, but after each stroke the victims were removed to make place for others, and were thrust down the sacrificial pits whether dead or alive.

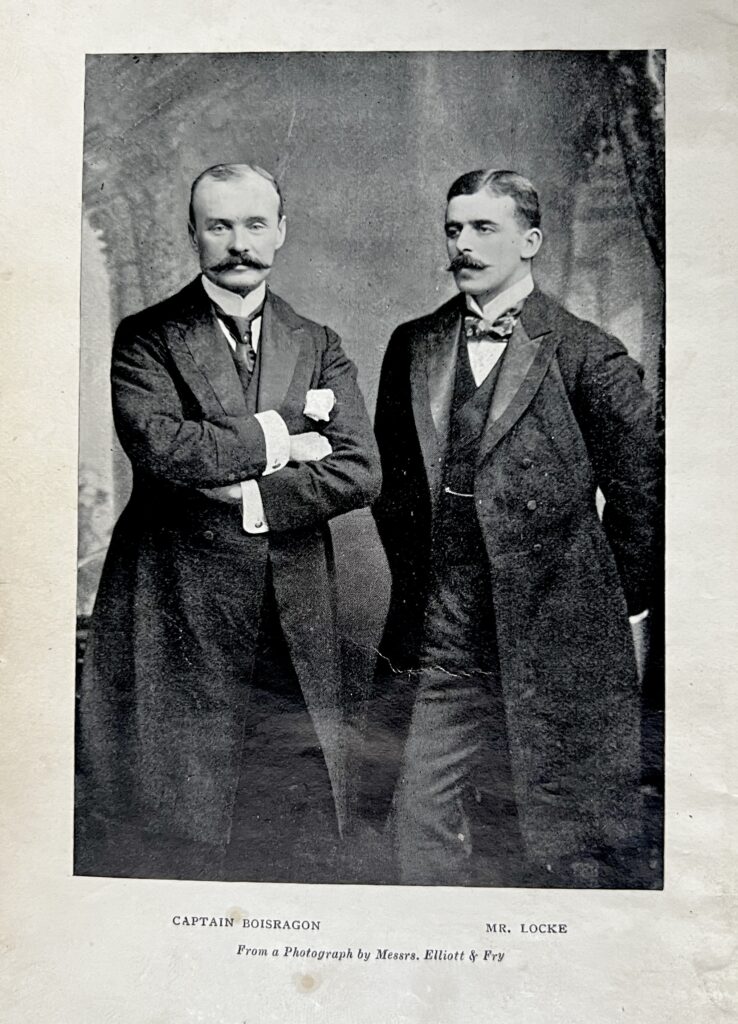

If you thought the sword in the photo above doesn’t appear very suitable for severing heads, there’s the explanation – it didn’t really matter. The human sacrifices would die in those deep pits anyway – though the British did find seven still just barely alive, and managed to haul them out.

Very soon the altars were running with blood and the priests and executioners were red with blood themselves and more like devils than ever; and, as each sacrifice was taken back to the pits, as many of the people as could get near them rushed at them and, dipping their hands in the blood, rubbed it all over themselves, till they were all red too, like the priests and executioners. At other times, it was the ceremony of the sacrifice on the crucifixion trees, and the victims for these were women.

When, after the first week, the supply of women slaves for crucifixion ran out, the Oba’s chiefs demanded Ibadan’s mistress too. Fighting them off, he was wounded, taken prisoner and had his head on a sacrificial altar, expecting to die at any moment, when he was reprieved by the Oba, who was both a childhood playmate and Ibadan’s cousin via his mother. The war chief was still bound and captive, still refusing to hand over his mistress, when the British arrived:

At last, one day, we in the City heard the sound of many big guns, and presently one big shot fell close to my prison. [This would have been one of the Expedition’s rockets]. Soon after that my door was opened and [my mistress] came to me and cut my thongs and told me that the white men were in the City and that the King and all the Binis had fled. Then the white men came and took us prisoners, but they bound up my wounds, and one of your Juju men touched them with ointment, so that they soon became well.

So these were the “ceremonies” for which the Cambridge museum’s sword was apparently used. Mass murder might be another way of putting it. Ibadan’s account both matches British reports of those weeks in every respect, though from the side which had no tradition of literacy, and shows the traditional contempt of a professional fighting soldier – accustomed as he was to deaths in battle – for extra-judicial murders.1

Nigeria’s campaign for restitution of the Benin bronzes has taken a beating this year, and as the Daily Sceptic has reported several times, its reverses have been largely self-inflicted. Now the post-colonial guilt industry appears to be shifting its attention to Laura Trevelyan’s slavery reparation campaign, and on September 1st Professor Brigitta Hauser-Schaublin published another of her hard-hitting articles.

In Cultural Property News, she lambasted the idea of rewarding descendants of Benin’s slave-trafficking regime by gifting to them ancient bronze works which have been admired and kept safe, albeit without sufficient context, in the world’s museums for a century and a quarter. Don’t miss Hauser-Schaublin’s astonishing third footnote, quoting a Nigerian historian.

Benin’s current Oba has never admitted or apologised for his ancestors’ crimes, let alone compensated their victims’ descendants. But this is nothing new: Oba Ovonramwen, after he was deposed and exiled in 1897, reportedly couldn’t see the problem with carrying on crucifying female slaves either.

1The local history can be confusing, some people being known by more than one name. Throughout Ibadan’s account, he refers to Oba Ovonramwen as “Adjumanni”. Ibadan himself can’t be the “Urugbusi” on p.68 of Barnaby Phillips’s 2021 book Loot, because this passage describes the failed resistance to the armed February 1897 expedition, not the assault on the unarmed January one. By February, Ibadan was a prisoner in Benin.

Phillips’s research was impressively thorough, but he appears to have been unaware of Ibadan’s interrogation in March 1897. It was provided to the South Wales Echo two years later by Capt. Alan Boisragon, Commander of the Niger Coast Protectorate Force and one of the two European survivors of the January 1897 Expedition, whose own The Benin Massacre (Methuen, London, 1897) was a best-selling account of that disaster and his escape.

It seems the British may have treated Ibadan as a soldier under orders – indeed, he was a prisoner of the Benin side and awaiting death when they captured him – and therefore didn’t put him on trial for the January 1897 massacre.

Stop Press: The Oba Ovonramwen referred to above is the same Oba Ovonramwen who was honoured with an installation at St Paul’s by a leading Nigerian artist last year. The installation was placed next to a much smaller brass plaque honouring Admiral Sir Harry Holdsworth Rawson, who led the expedition that deposed the Oba. You can read about this installation on the BBC’s website, which – shock! – makes no mention of the ritual sacrifices carried out during Ovonramwen’s reign. Here’s an extract from the BBC’s ludicrously one-sided piece:

This image of the oba, or king, of Benin dominates the space, through which thousands of visitors pass every week, and draws the eye.

Next to it – barely readable and tarnished through time – is a much smaller brass memorial plaque in honour of Admiral Sir Harry Holdsworth Rawson, who led a punitive expedition in 1897 to the West African kingdom of Benin.He oversaw the British soldiers and sailors who destroyed a centuries-old civilisation, looting and burning down the oba’s palace in what is now Benin City in the Nigerian state of Edo.

Their looted treasures – thousands of metal sculptures and ivory carvings made between the 15th and 19th Centuries and collectively known as the Benin Bronzes – are now at the centre of a debate about the return of artefacts taken during the colonial era.

But as his plaque recalls, Rawson was revered at the time for his exploits right across the British Empire.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Truth is stranger than fiction because fiction is obliged to stick to possibilities whereas truth isn’t”——Mark Twain. —-Perhaps silly Liberal Progressives need to cut out all the fiction and check out some TRUTH

In the 20th century the Marxists murdered at least 100 million people. In Russia 18 million people passed through the Marxist slave-camps. Yet dimly flickering fragments of humanity like Sally Rooney still think there’s something wonderful about Marxism. Weird.

Pol Pot

Mao

The Kim dynasty

“dimly flickering fragments of humanity like Sally Rooney”

Now that is poetry.

Thank you.

Interesting, isn’t it?

It’s OK to be a communist.

For me anybody who declares his/her support for communism effectively says “yes, I think Lenin’s idea of the red terror was a great one, the forced labour camps and the summary executions were a fantastic way of keeping the population under control and there is a lot to be said for mass famine and starvation”.

“The Bolsheviks started out with the determination to remedy the abuses of Tsarist Russia. Under the Tsars, about 17 death sentences were carried out each year. The communist revolutionaries thought that outrageous. They screamed bloody murder: The death penalty should be abolished. However the contract contained a small footnote: In the beginning, there still would be executions it it was necessary to install communism itself as a system. In the first months after the Russian Revolution of 1917, there were 540 executions per year; after a few years, this increased to 12,000 per year; and between 1937 and 1938 more than 600,000 executions were carried per year.

Even more astounding than the numbers of victims was the arbitrary way in which people were sentenced to death. Each city and region was given weekly and monthly quotas that stipulated how many ‘traitors’ had to be arrested. If, at the end of such a period, the local mandate holders observed that the target number had not yet been reached, they took to the streets and arrested people at random:”

Extract from The Psychology of Totalitarianism by Mattias Desmet.

Never heard of Sally Rooney. I don’t read any contemporary fiction. Still working my way through my parents’ book collection – that will keep me going for the rest of my days. Default assumption is that anything contemporary will be bollocks. There are hundreds or thousands of great works of literature I haven’t read. I feel no need to buy or read the “latest thing”.

Couldn’t agree more, although there is a contemporary work here and there that’s worth reading; it’s just that finding such rarities is so time consuming – while finding great works of art that were produced in the ‘past’ – a country Rooney doesn’t care to visit – is easy. So much great art to absorb, so little time. Rooney and her ilk just don’t matter.

Not long ago, the prospect of nuclear annihilation was the favoured excuse for non-fecundity, so the prospect of an imaginary climate apocalypse seems a remarkably feeble pretext. It wasn’t always thus – my sisters were both born in the darkest days of WWII, when a Nazi victory was a real possibility. (I’m a post-war boomer – boo, hiss(II)).

Tucker’s very enjoyable review of Rooney reminds me of the Beachcomber character who wrote “A marvellous book – I look forward to reading it!”.

I don’t quite get why somebody who starts off with ‘ I’ve never read any of her novels and I don’t intend to start now,’ has been given the task of her character assassination? That is just pure bias for its own sake. A massive drop in journalist standards by the Daily Sceptic here I’m afraid. I don’t agree with Hitler or Mao but at least I made an effort to read their writing before criticising.

I was disconcerted by his opening line too, but actually I got Tucker’s point pretty quickly, his dismissal of Rooney’s work without even reading it becoming perfectly acceptable to me: contemporary writing is sooo predictable – why waste one’s time with it? That’s not to say that nothing produced today is readable – but Rooney has been so repitively clear from the start about her views – she’s so much a purveyor of millennial angst and nothing else, and sooo happy to publicize it – that the assumption that this is just more of the same is probably justified. And “probably” is good enough for me, given how much good stuff there is out there. After all, Rooney herself is a fan of not reading things (see the ‘pre-1921’ reference in Tucker’s article). In the case of many writers, contemporary and otherwise, I’d agree with you; but you can smell the assembly-line predictably of Rooney’s views from a mile off – and, in the same vein, a big body-swerve of the kind that grown-ups give on principle to the effete 20/30/40-something tattooed, purple-haired, pierced brigade is a sign of maturity to me. I just know what they’re going to say.

It was hilarious. I loved it.

So did I!

What a miserable sounding vacuous, ignorant old woman – even though she’s 30 something

Never mind the politics, feel the grammar. I might be influenced by my early education in parsing and analysis of sentences, but a writer who can say “Me, my family and friends, we……” fails the 11+.

This was brilliant . Thank you. I too viewed Sally Rooney through the lens of looking at who read her. It’s the sort you overhear in Hackney. The poseur childless. I guessed her ‘characters’ enjoy the navel gazing of privileged post-university students aiming well-rehearsed barbs at the privileged. Novels have to write stinging dialogue because it’ snot as if the characters haven’t been able to think about what they are going to say.

Rooney produces derivative dystopian self indulgent and dim output. The unutterably stupid protest against Baillie Gifford sponsored literary festivals is a spectacular own goal. A fund manager which invests more than any others in a post carbon world. A poorly considered narcissistic own goal which harms literature and allows her to feel good about herself while revealing intense ignorance..

Her books are dreadful according to my daughter who is 24. Well she only bothered with Normal People. My son is in publishing and he his opinion was lower.