In week two, Sir Christopher Wormald, Permanent Secretary at the Department of Health, gave evidence and provided some of Monday’s most memorable quotes:

Question: “’The National Risk Assessment [towards the bottom of the page] is a strategic medium term planning tool. Risks captured within the NRA [the national risk assessment] are examples of civil emergencies that could plausibly affect the United Kingdom within its territorial boundaries in the next five years… It is crucial all risks are assessed using a consistent, evidence-based approach.’ What is an evidence-based approach?”

Wormald answer:“I think it’s exactly what it says on the tin, so that it should be on the basis of expert opinion, modelling and the available evidence.”

Question: “An approach that isn’t based on available evidence isn’t much of an approach, is it? ”

Answer: “Well, I mean, Government is sometimes in the situation where it has to take decisions despite lack of evidence, so that does happen.”

Our readers will already be squirming on the seat at Sir Chris’s triad: first comes expert opinion, then modelling, the modern version of star gazing, and finally, evidence. Note it’s not the best available evidence; any old evidence will do.

There is no question that the Government took decisions despite a lack of evidence in the face of the precautionary principle.

What is unforgivable is the retrospective attempt at justifying these decisions using poor quality evidence and the refusal in the presence of uncertainty to conduct prospective good quality studies to generate reliable evidence.

Essential reading for the inquiry team is the James Lind library essay: ‘Why treatment uncertainties should be addressed.’

When you have little understanding of science and rely on expert opinion and modelling, that is your legacy: an evidence black hole. What happens next is anyone’s guess, but intervening in healthcare matters is never risk-free and ignoring uncertainties will inevitably lead to harm.

Next up. David Cameron, the former Prime Minister, did a fine performance of ‘it ain’t me guv’ when asked about preparedness for the F word: Not surprising that Dave thought there was only one pathogen in town during his reign as PM. It shows you what happens when you have advisors with tunnel vision.

He and the current Chancellor are, as one, on the same topic: contrition.

Question: “Jeremy Hunt, in his statement to the Inquiry, has said, ‘I believe with the benefit of hindsight that our preparations… were affected by an element of ‘groupthink’. By that I mean that the spread of many distinct types of virus could create a pandemic, yet our shared belief was that the most likely scenario was a pandemic flu.’

“What do you say about that?”

Cameron’s answer: “So it’s true that our expert advice was that pandemic flu was and actually continues to be the biggest risk. You’ve talked at some detail today about the range of other pandemics.”

Warnings were out there and still are. But until 2020, there was only one pathogen in town: influenza. Politicians continue using the F word to confuse everyone or perhaps because they are confused.

However, things have changed; three pathogens are now in town: SARS-CoV-2, Influenza (camouflaged with the C and F words) and RSV. By sheer coincidence, these are the only three agents with licensed pharmaceuticals. The known rest have no role (until one of them or their kin is determined to be novel); then, they can join the list of agents for another pandemic. Beware, though, if one of them is rhinovirus, then we’re in trouble. They are responsible for much more than the common cold, and the three species (A, B, and C) include around 165 recognised types.

But it’s OK because Clara Swinson, Director General for Global Health (previously known as Global and Public Health), does not think any groupthink occurred.

On Tuesday, we had to don a life vest so as not to drown in a flood of crocodile tears.

The former CMO, Dame Sally Davies, apologised to the bereaved families and presumably for her groupthink (according to her, there was groupthink). So which is it to be? Group or critical thinking? Beware, though, in these times, adopting the latter thinking can lead you down the path to suppression, censorship and surveillance – sticking with the group, however, leads to a much better chance of honours.

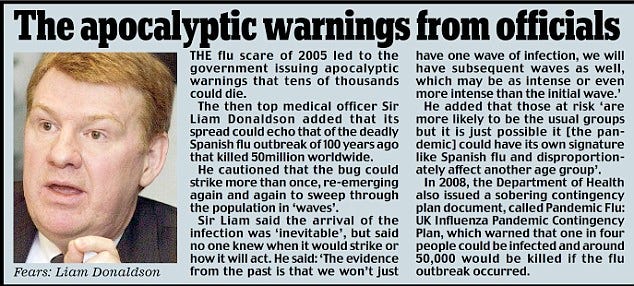

Groupthink must have been why Dame Sally tried to close our antiviral review down. She and her predecessor Sir Liam Donaldson (enthusiastic stockpiler of antivirals), were instrumental in whipping up the fears, the ‘influenza only’ narrative and the ‘apocalyptic warnings’. As our readers know, we have received the same treatment (plus been the object of ‘surveillance’) during the Covid pandemic.

We’ve written about the lack of preparedness for winter multiple times. Does anyone remember the Coffey plan, and will it work for the NHS this winter? We also pointed out that the answer to the recurring ‘winter crises’ is staring us in the face. So, it’s worth pausing and considering if the health service isn’t prepared even for winter; what’s the point of asking about pandemic preparedness?

However, all is not lost: We found a point we agree on from day two:

The KC asked, “Given what you’ve just said, Mr. Osborne, about the fact that not every eventuality can be predicted or planned for, I’d like your view on what Sir Mark says here at paragraph 86:

‘Every national emergency has knock on effects on citizens’ lives beyond the immediate impact of the emergency itself – and there is always the possibility that the ‘cure’ for the specific emergency in terms of the policies and actions directed at stemming the primary damage causes harmful ’side effects’.’”

Why, then, were the harmful side effects not part of the discussion when deciding to intervene?

As for Osborne’s answer, for once, we’re lost for words.

Osborne’s answer: “I mean, yeah, I mean, this – you know, I know Mark very well and have worked with him, you know, this goes, to my mind, the heart of the, you know, very difficult question that the government of the day had to wrestle with, and any future government will have to wrestle with, which is, you know, what is the – what are the costs and benefits of dealing with the health problem, the spread of the disease, versus the impact of closing a school? I had school-age children at the time of the pandemic. You know, closing the court system so that people don’t get their trial. You know, locking down prisoners in prisons. You know, all sorts of other things that, you know, had a really –”

Question: “Yes.”

Osborne’s answer: “– damaging impact, and, you know, you go to the heart of very difficult sort of societal questions, of which frankly I don’t – you know, you can produce any amount of economic analysis of what’s the, you know, benefit of, you know, controlling coronavirus for a day and shutting a school for a day, but I think in the end they come down to essentially kind of human societal judgments of what are the things we value, and the truth is, you know, different human beings will value different things. Some people will say the education of the child is more important than, you know, protecting older patients in, you know, our care homes. But that – I mean, that – ultimately, we have democratic governments that are accountable to the general public in order to try and make those very difficult decisions.”

On day three, the lineup included Sir Mark Walport, Oliver Dowden and Jeremy Hunt.

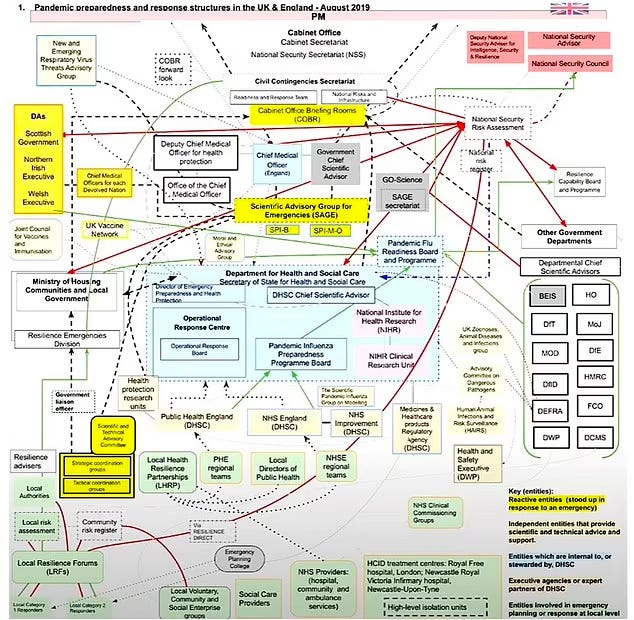

The discussion with Sir Mark quickly turned to the structure of the Government’s decision-making.

Question: “This is our rather complicated –”

Walport’s answer: “Ah, yes, worrying diagram.”

Question: “Yes, diagram.”

The diagram is genuinely complicated. Try the pandemic decision-making game: follow a path until you end up at an organisation you’ve never heard of.

We ended up at the Emergency Planning College – they apparently deliver “crisis management, resilience training and allied services.” This is subject to “our well established Government assurance of quality”. How reassuring.

Jeremy Hunt said that quarantining people sooner “might have avoided” the first Covid lockdown. No surprise there, then. In his bid for the top job, he was considered a ‘lockdown fanatic’ who would have shut down the U.K. economy in a bid to emulate China’s zero Covid policy.

But note the word “might” in his statement. Surely, this was the chance to interrogate the witness – what is this based on? Where is the evidence to back up the claim?

He added lessons from East Asia over the SARS and MERS outbreaks weren’t learnt. And guess what? He wished he had done more to challenge the favourite word of the week, ‘groupthink’, over this.

We wonder if there is a problem in the inquiry with the availability heuristic. Are witnesses to the inquiry recalling events based on how easily they can recall similar events in the preceding days? It’s why you keep the jury away from the media. As an issue comes up, is it becoming more readily recalled as the nub of the problem? All will be forgotten by next week, and we’ll be on to the next issue.

On day four, the real heavy hitters of science emerged: Sir Chris Whitty, the CMO, and Sir Patrick Vallance, the former Chief Scientist Advisor, were up on stage.

We learnt from Sir Chris that SAGE people don’t “have the competence to assure government that they’ve considered the economic problem and they can now give a central view on it. I think that would have to be done separately.” This will be pushed to module two, but is it an early foray into what we can expect in module two – what wasn’t considered when locking down – the cost?

Despite this, Sir Chris thought lockdowns “was an extraordinarily major, social intervention with huge economic and social ramifications”.

Sir Patrick Vallance “thought there was a paucity of data, which meant – and I say that in my statement – that on many occasions it meant that you were flying more blind than you would wish to”.

Beyond this, there wasn’t much to write about on day four. At the end of each transcript is an index of mentioned terms – it gives you an inclination of what’s on folk’s minds. The good old groupthink got three mentions, and topping out the list was SAGE, with 63 mentions. However, care homes got a measly two mentions – a lack of interest in older people and the vulnerable regarding prevention doesn’t bode well.

The website of the inquiry for downloading documents now runs to 60 pages – those interested in the findings will have to be in this for the long haul – there’ll be thousands of documents to trawl through by the time the game is up.

On Monday, we learnt something rather odd. We’d like our keen-eyed readers to clarify our understanding.

Mr. Keith: “My Lady, I’m extremely sorry to have to get to my feet. My learned friend knows very well that we’re constrained by the rules of Parliamentary privilege, not to be able to put Parliamentary material which includes NAO reports in a way which calls into debate the merits of whatever conclusions have been drawn by the particular Parliamentary body or anything in fact said in the chamber of the House of Commons. So I’m just a bit concerned that we may be breaching Parliamentary privilege by going down this line of examination.”

If we are reading this right – please correct us if we aren’t – the Inquiry can’t question any conclusions arising from Parliament that are already documented.

By creating a market, you have to feed it, do you not? So after ignoring evidence and warnings, continuing to use the F word and shedding tears and apologies, will someone with minimum competence and who can exercise independent thinking take over? Preparing for the expected meant the Government was ready for what the advice told them, not for the unexpected.

However, the culprit for week two – unlike last week, where it was Brexit that did it – seems to be groupthink.

Walport’s answer: “I think that, I mean, to some extent that depends on the chairing and the chemistry of the meeting, frankly. My experience of chairing groups of scientists is that groupthink is not something that they are particularly fond of.”

Hmmm – how did all the advice reach the same conclusions over lockdown if groupthink was off the menu?

Dr. Carl Heneghan is the Oxford Professor of Evidence Based Medicine and Dr. Tom Jefferson is an epidemiologist based in Rome who works with Professor Heneghan on the Cochrane Collaboration. This article was first published on their Substack blog, Trust The Evidence, which you can subscribe to here.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

The point about evidence is telling. If you claim that your decisions at the time were on the available evidence but there wasn’t much available (not true, IMO) then surely you put in place measures to gather that evidence. But it wasn’t really done anywhere as far as I know – all the experts across the world spent their time and energy telling us to follow their evil edicts and why we must ignore alternative views and treatments. But they never seemed to have learned anything about the “novel virus”. Whyever could that be?

Waste of time and money.

Anyone with half a brain knows it’s going to be a very expensive whitewash that keeps Guardian readers et al in a feeding frenzy, and er, that’s it.

Good luck to Drs. Carl Heneghan and Jefferson though. I’m sure they’ll continue to be ignored, sadly.

Off topic –

All that said, of vastly more importance (maybe), I trust our resident Putin Badman/The USA/West Good, is limbering up nicely for a most illuminating and deadly attack on Russia, again.

Maybe he’s just waiting to see which way the chips fall.

Clue – see what happened in WW2. Russia ain’t going to lose.

https://www.globalresearch.ca/they-want-implement-global-system-digital-identification-for-all-connected-our-bank-accounts/5823395

According to this short article digital ID is going to be introduced in September this year.

The end game.

Hux this is as you say “The End Game” it Trumps everything in Human Existence to date !

If you think about it , the level of collateral damage we have all taken for 3 years both mentally & physically is off the scale & we wonder how it can go on unchecked as the truth about what’s been done to us comes out ! Their only route to escape our wrath is to coral us into the digital banking ID prison before their house of bullsh1t cards collapses !

I doubt humans have become more evil but there’s no doubt their means of exercising their evil is growing exponentially. That’s my worry, and why I think that our default position must be to trust nothing and nobody.

Over 20 years I trained more than 20,000 people in the art of peer review.

The essence of a safe review is twofold: competence and true, political independence.

This establishment-led travesty is simply an expensive sop, funded by taxpayers, the victims of lockdown, whose primary purpose is to ensure none of the powers are held to account. It will exonerate politicians, scientists, bureaucrats, MSM and big pharma.

Token slaps on wrists for a few. No-one will go to jail.

Can we move on now, please.

$cience summed up

https://www.rt.com/news/578687-harvard-professor-fake-honesty-studies/

I know we’ve seen loads of these compilations now but it does work as a handy 4min reminder of just how much we were maligned, vilified, scapegoated and abused, all for behaving like critically thinking and rational people who remembered a bit of high school biology and what our immune systems were designed for. The nonsensical garbage spouted is just off the charts. We’re on a par with drink drivers apparently…Oh, and they have the flaming gall to talk about censoring ‘hate speech’ and ‘misinformation’! Well I think all of this qualifies;

https://makismd.substack.com/p/video-covid-crimes-us-media-attack

W-nkers ! All of them !

I’ve just come back from church, where a couple based in Manila described what they have been doing the past 15 years. They founded a church next to a rubbish dump, which the poorest of the poor scavenge for food and other goods. They mentioned that the Philippines closed the schools for almost 2 years, effectively leaving the local children imprisoned in the squalor of their own homes. Doubtless the Philippines were copying what seemed to them the well-informed best practice of the West – and some. Decisions in the UK and other western countries had consequences well beyond our own borders. The Lord will hold us to account, even though the parliamentary enquiry fails to.

I do not share your faith but I hope you are right

The so called government of the UK and all their lackeys totally cocked up the country’s responses to Rona. So where in the rational world will there be any acceptance of this incompetence during this joke of an Inquiry? Spoiler alert – nowhere.

I already know this enquiry will be a whitewash from the disproportionate number of people responsible for the damage caused by the government restrictions who remain in positions of power and influence are being inadequately cross-examined and deferred to in that inadequacy because of their position. They are responsible for such great harm that they should be questioned without mercy and forced to accept their responsibility. The results of questioning so far makes me think the lawyers involved so far, either are so ignorant that they don’t know what to ask, or are part of the intent of those in power to ensure this enquiry is a waste of time whitewash and will allow the controls gained under covid to be used again without question.