Just because you can do something, should you?

This is not just a question people should ask themselves as they stare at the last piece of pizza but in many other circumstances as well.

And certain people need to ask it more often – scientists, for example, with the potential power over life or death, and world-changing breakthroughs or devastating disasters.

Like Captain Ahab and his maniacal chase of the white whale Moby Dick, sometimes – quite often, actually – obsessively doing something just because you can and really want to may not be in the best interest of everyone else.

Gain of Function (GOF) research is a perfect example of this problem.

The general definition offered to the public by officials during the pandemic was this: GOF takes a virus and enhances its lethality or transmissibility amongst humans in order to be able to study the resulting bug to speed the search for a potential treatment if and when the virus evolves in nature to the same danger point.

In other words, if scientists can work with the possible superbugs now they can get a ‘head start’ and be better prepared to fight them in the future if they should appear naturally (zoonotically) and threaten humans.

By that definition – a common, descriptive and precise definition – gain of function has never worked.

The risk-reward calculation under those circumstances is very clear – near-zero chance of reward for performing a highly risky act.

Possibly even more importantly, it can never work as advertised, in part because natural evolution is impossible to predict in a lab.

But what about scientific processes that seem a bit like GOF but are not? Is, for example, the fictional creation of dinosaurs in Jurassic Park similar? Can breeding dogs over generations to accentuate a trait be considered in the same family? How about cross-pollinating roses to get a new colour?

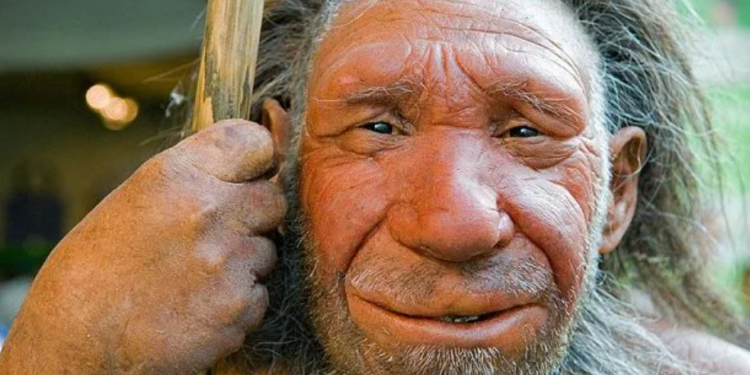

Or, how about, as was announced this week, the ability to ‘revive’ Neanderthal-era bacteria?

What this team has done is harvest ancient bacteria from a calcified Neanderthal tooth, tease out what remained of the genome, splice it together and voila! – a bacterium (a paleofuran) that had not seen the light of day in thousands of years.

The newborn bug – and the process behind it – could, amongst other things, say researchers, hold potential for new drugs like antibiotics that would be beneficial for us mostly non-Neanderthals today.

“This is the first step towards accessing the hidden chemical diversity of earth’s past microbes, and it adds an exciting new time dimension to natural product discovery,” Martin Klapper, PhD, postdoctoral researcher at the Leibniz-HKI and co-lead author of the study, said.

So, does reviving ancient life fall under the GOF rubric?

No, it doesn’t, for a number of reasons.

First, the process does not even approximate that used in GOF.

Second, the scientists involved actually have a very good idea of what they could end up with in the end, while GOF is a serial amplification process to see how nasty it can make a bug, to ‘see what will happen’.

Third, there is clearly no intention to purposefully make something that is specifically more lethal to and more transmissible amongst humans as GOF (in the current context) does.

“This would not qualify as GOF research or ePPP (enhanced potential pandemic pathogens) research under the U.S. policies,” said Dr. Richard Ebright, a Board of Governors Professor of Chemistry and Chemical Biology at Rutgers University and Laboratory Director at the Waksman Institute of Microbiology. “And because it is not reasonably expected to generate a serious pathogen it probably would not count as GOFROC (gain of function research of concern).”

Obviously, any new technological process can be warped by bad actors, but it seems clear that this achievement is just that – a real achievement.

Other biotech and genetic engineering to bring back former creatures could also fall under a similar rubric, though some aspects of the ‘de-extinction’ effort do raise other certain concerns.

For example, most have heard about the effort to bring back the woolly mammoth. This effort is being championed by (amongst others) a company called Colossal and definitely has a literally warm and fuzzy feel about it.

But ethicists have warned – like with Ahab and his whale – that the such efforts may not be a good idea.

It must be noted that these efforts do not occur in a vacuum and companies are for-profit ventures that have investors to satisfy, either financially or informationally. In Colossal’s case, one of those investors is In-Q-Tel, the venture capital arm of the CIA.

Yes the CIA really funds – to the tune of reportedly about $120 million a year – an ‘independent’ venture capital fund that invests in tech startups. You can see the spy agency’s portfolio – which includes the notorious Palantir – here.

While the Neanderthal bacteria is a neat piece of science and could have a real – and potentially very positive – benefit, the scientific process – the method, the ethics, the motivations, the desires – can easily fall prey to the nefarious.

In his famous Farewell Address, President Dwight D. Eisenhower did not only warn of a “military-industrial complex”, but also of the perils of scientific ‘white whales’ and other research being funded by the Government:

The prospect of domination of the nation’s scholars by Federal employment, project allocation, and the power of money is ever present and is gravely to be regarded.

Yet in holding scientific discovery in respect, as we should, we must also be alert to the equal and opposite danger that public policy could itself become the captive of a scientific-technological elite.

Thomas Buckley is the former Mayor of Lake Elsinore, California and a former newspaper reporter. He is currently the operator of a small communications and planning consultancy and can be reached directly here. Subscribe to his Substack here.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Let me get this straight. We (mankind) are not doing enough research into new antibiotics to combat existing bacterial infections. The only solution is to create a new* bug and research antibiotics against that? Looks like research funding is being misdirected again.

*Yes, I know the article is about an ‘old’ bacterium but if it’s new to science it’s ‘new’.

It’s like they’ve taken the lid off the Pandora gain-of-function sweety jar and simply don’t want to put it back on. Until we’re all dead.

It might be a good idea to put the money to better use and start filling in the thousands of potholes in the countries roads..

I don’t want my tax money filling in potholes in roads in any other countries, thanks.

Potholes in my own country’s roads, OK, maybe.

😉

Well I was talking about the UKs.. what country are you talking about.. haha 😉

I could name a good few things that might fill the potholes. We have them here too. If I was a conspiracy thinking type, I’d think that there is an agenda to run down the road system and damage the car stock…

Yes and we certainly don’t want to fill the potholes with money.

“Neanderthal bacteria” never went away. Neanderthals still exist. I mean this seriously, by the way, and not as a term of reproach for people like, say, Matt Hancock.

All I can say to these In Q Tel people is “please GOFROC yourself.”

It’s like suggesting that we move the planet into the path of all the planet-killing comets and asteroids out there to look at what killed off the dinosaurs.

Gawd, scientists are a pessimistic bunch aren’t they? Surely we have all bases covered nowadays in terms of antibiotics, antivirals, many other medications, nutraceuticals plus advanced medical technology and healthcare in general. We’re hardly going to fare as badly as in the Middle Ages when the Black Death ravaged the globe and people had basically nothing to fight it with, so I think the amount of expense and all round faff involved in this endeavour cannot be remotely justified. Scientists just like tinkering and generally mucking things up, which demonstrably results in a massive crapfest. Leave zombie viruses and bugs dormant and where they can do no harm…or safely in the fictitious plots of sci-fi books/movies.

Seconded Mogs.

Next step, digging up the bodies of Black Death victims to analyse the Black Death… just in case. Application to the Wuhan lab!

Now, now Dom, no giving Billy ideas.

Am I the only person who got the ‘take home message’ from the film ‘Jurassic Park’..?

Gingers are ginger because of the Neanderthal gene, allegedly. Explains a lot.

Dammit, that face is so intelligent! He’s got a knowing look about him that I could warm to, although he’s not blessed with conventional good looks.

I could do without his bugs, though.

There’s no antiviral in the world that would make it worth doing this stupid thing just to prove that they can. We’ve got plenty of drugs already – they just keep banning the things as soon as they go off-label.

I’m developing a strange interest in Barbara O’Neil’s old-wife remedies: I doubt you’d get serious side effects from sticking an onion poultice on your ear if it ached.

And have you seen her video about cayenne pepper? First aid in the event of heart attacks?