How many COVID-19 vaccine related serious adverse events are acceptable? In part 1 of this two-part article, we tried to answer this question by reference to the population and the ‘collectivist’s’ view. But when it comes to medical treatment it is the individual that is paramount and not society. Some of the greatest medical abuses of history have been justified through the ‘benefit to society’ argument and this is why ethical frameworks in medicine focus on the individual patient and the benefit and risk to him or her, and him or her alone.

There may be incidental benefits to society, but these are additional effects of treatment and not its purpose, which must be to benefit the patient. This latter point is made in the ‘Green Book’ in the opening sentences from the chapter on informed consent for vaccination (Chapter 2).

It is a legal and ethical principle that valid consent must be obtained before starting personal care, treatment or investigations. This reflects the rights of individuals to decide what happens to their own bodies and consent is a fundamental principle of good healthcare and professional practice. (our emphasis)

No mention of broader societal consideration here, but a very clear statement as to whose rights are important. So, in thinking about what is an acceptable level of serious adverse events (SAEs) from the COVID-19 vaccinations, we need to bring it down to the individual level and be able to describe the benefit and risk to the person receiving the vaccination. If there are genuine benefits to the individual, then these may well produce population level benefits, but ultimately it is the individual who needs to decide on whether the treatment will be of benefit to him or her.

A point that the Green Book goes on to make when discussing what valid consent means:

For consent to immunisation to be valid, it must be given freely, voluntarily and without coercion by an appropriately informed person who has the mental capacity to consent to the administration of the vaccines in question. (our emphasis)

So, what does “appropriately informed” mean when it comes to the benefits and risks of the COVID-19 vaccinations to the individual?

The 90% ‘lie’

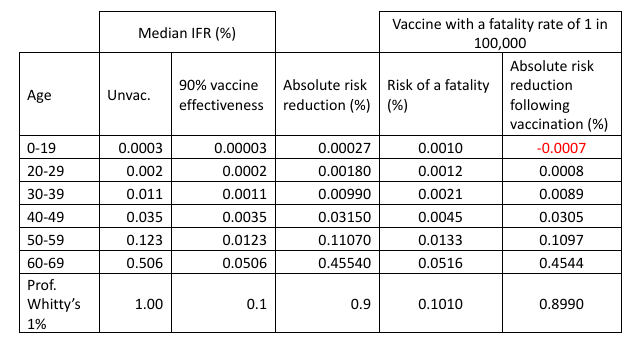

To be appropriately informed first means understanding how serious COVID-19 is to the person who is going to potentially receive the vaccination. We can get a sense of this from estimates of the SARS-CoV-2 infection fatality rate (IFR). A relatively recent paper by Pezzullo et al. gives just such estimates of the IFRs for different age groups based on a meta-analysis of 31 pre-vaccination studies. These are summarised in Table 1 and give us our baseline ‘seriousness’ by which to measure the individual effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccines in preventing death. Obviously, these are median figures and so if you are someone who has a pre-existing condition that raises your risk above this level, but this speaks to the need to understand your own risk (and benefit) if you are to consent to treatment.

Two things leap out from this analysis. First, the ‘ageist’ nature of COVID-19; for those under the age of 19, the likelihood of dying from SARS-CoV-2 infection is three in a million, whilst for those in the 60-69 age group it is 1 in 200. Second, none of these IFRs comes close to the 1% that Professor Chris Whitty used as his theoretical example of a disease with a low mortality rate for which he said:

For a disease with a low (for the sake of argument 1%) mortality a vaccine has to be very safe so the safety studies can’t be shortcut. So important for the long run.

Having established how serious COVID-19 is to oneself, the next question becomes what benefits do the COVID-19 vaccinations offer with respect to the likelihood of dying from SARS-CoV-2 infection? The ONS figures on vaccine effectiveness suggest that the COVID-19 vaccines have an initial relative effectiveness of 90% in preventing COVID-19 related deaths and this ‘90% effective’ benefit is routinely used as the justification for getting vaccinated. But, putting aside the question as to whether this figure is accurate or not, what does ‘90% effective’ actually mean? Well, for the 0-19 year-olds this means we changed their risk of dying from SARS-CoV-2 infection from three in a million to three in 10 million, which is indeed a relative risk reduction of 90%, but is an absolute reduction in risk of 0.00027% (Table 1). Whilst for the 60-69 year olds the risk of dying of COVID-19 has gone from 1 in 200 to 1 in 2,000, an absolute reduction in risk of 0.45%. The benefit to the 60-69 year-olds is about 1,700 times greater than to the 0-19 year old, despite the vaccine being (for the sake of argument) ‘90% effective’ in both groups of people. For a disease with a ‘low mortality’ IFR of 1% the vaccine reduces the risk to 0.1%, an absolute reduction of 0.9%.

So, in terms of being ‘appropriately informed’, being told that the vaccine reduces your risk of dying “by 90%” is the great statistical ‘lie’, because it potentially leads to a complete misunderstanding of the real benefit to you as an individual. For example, if you are a healthy 20-something year-old then a ‘90% reduction in risk of dying from COVID-19’ sounds like a great benefit from vaccination because it tacitly suggests that you are at significant risk from COVID-19 itself. That is until you realise that a 90% reduction in risk really means reducing your risk of dying from COVID-19 from 1 in 50,000 to 1 in 500,000, an absolute risk reduction in the IFR of 0.0018%. A trivial gain in overall risk reduction following a SARS-CoV-2 infection.

So much for the benefits, what about the risks – what is the risk of suffering a fatality following a COVID-19 vaccination? As discussed in part 1, estimates of these figures vary from 12 in a million for the mRNA vaccines to potentially as high as 1 in 5,300 for the AZ vaccine. If we focus on the mRNA vaccines (not least because it appears that the AstraZeneca vaccine is being quietly dropped from use) and for simplicity’s sake assume that the risk of a vaccine induced fatality is 1 in 100,000 per dose for everyone receiving the jab (10 in a million), then what does this mean for an individual’s risk of dying if vaccinated against COVID-19? Now we need to consider not just the residual chance of dying from COVID-19 if vaccinated (assuming 90% effectiveness) but the added risk of dying from vaccination itself which means simply adding the two risks together to get the overall risk of dying (Table 1). We can then go on to work out what the absolute risk reduction is if we take this rate of vaccine fatality into account. Doing this, it is immediately apparent that with a 1 in 100,000 level of vaccine fatality, vaccinating children and the under-19s actually increases their likelihood of dying by about three-fold (from three in a million if unvaccinated to 10 in a million if vaccinated) and for those in their 20s, this level of vaccine fatality halves any gain from COVID-19 vaccination (from 0.0018% to 0.0009%), because the absolute risk reduction from even a ‘90% effective’ vaccine is so modest that it is impacted by the 1 in 100,000 chance of a vaccine induced fatality. For those more at risk from COVID-19, this level of vaccine fatality does not substantially alter the overall benefit of vaccination, although the absolute reductions in risk remain modest.

The benefits to an individual of having a COVID-19 vaccination are not just about reducing one’s risk of death, but also avoiding potentially serious illness. A full-blown bout of COVID-19 is a deeply unpleasant experience, which might end up in a trip to hospital and so having a jab to avoid serious illness is also of genuine medical benefit. But, as is obvious from the definition of an SAE (see part 1), vaccine-induced injuries and SAEs can also be truly awful, and even life-altering, without necessarily being fatal. More people will benefit from any positive impact of the vaccine on serious disease, but similarly more people will also suffer non-fatal SAEs and so, the real balance of benefit/risk comes from understanding these broader impacts of the vaccination. As discussed in part 1, effectively quantifying such benefits and risks outside of a clinical trial is very difficult as we’re depending on spontaneous reporting and there will be lots of assumptions and biases in the analyses. In the end, we can only really focus on ‘countable’ things like deaths and hospitalisations but the vast majority of potential benefit (reduction in disease severity due to COVID-19 vaccination) and injury (SAEs and AEs that are still significant and potentially life altering) will not be reported and so will be invisible to the assessment of benefit-risk.

Multiple doses

But there’s a further consideration we need to take into account when trying to be ‘appropriately informed’ about the benefit and risk and that is that a COVID-19 vaccination is not a single jab but multiple jabs. This is necessary to achieve (and maintain) the ‘90% effectiveness’ of the vaccination, but each dose carries the risk of an SAE and so to really understand the risk means figuring in the impact of needing to have several injections, in other words what is the overall risk for the vaccination course?

Let’s assume that most SAEs are not fatalities and that the SAE rate associated with the mRNA vaccinations is 10 times higher than the potential fatality rate i.e., 1 in 10,000 per dose (which would still be classified as very rare events). What does this mean if you were to have a course of three jabs i.e., primary dose and then two boosters? To calculate the risk across all three doses, we need to work out how likely you are to not have a vaccine induced SAE for this course of treatment. For each dose the odds of not having an SAE are 9,999 in 10,000 or 0.9999. For all three doses, the odds of not having an SAE are therefore 0.9999 × 0.9999 × 0.9999 = 0.9997. Which means the risk of a vaccine SAE over the three-dose treatment course is three in 10,000 (1–0.9997 = 0.0003) or about 1 in 3,300. The risk over all three doses is substantially greater than from an individual dose, although each dose carries the same 1 in 10,000 risk.

In contrast, the benefit does not increase with multiple doses. In fact multiple doses are required if we are to receive the ‘90% effective’ benefit, assuming that it is actually this great in the first place (see for example these two discussions on vaccine effectiveness). Even assuming the original vaccine effectiveness was 90%, because the current COVID-19 vaccinations are against variants that are different to those endemic in the population now, the effectiveness of subsequent ‘boosters’ actually drops off, meaning that the assessment of benefit and risk must also change for the new variants compared to the original variants. Obviously, anything less than this ‘90% effective’ figure proportionally reduces the benefits discussed here and the consequent balance of benefit and risk.

Overall, understanding the benefit-risk ratio of any treatment can be a fluid thing, especially for an evolving infectious disease like COVID-19, and so it needs to be constantly reviewed and refined. As a result, it turns out that being ‘appropriately informed’ about your individual benefit-risk for the COVID-19 vaccinations is extremely difficult, despite the billions of doses that have been given to people around the globe.

Final thoughts

The issue is not that the COVID-19 vaccines have SAEs, all vaccines carry some risk of such adverse drug reactions. The issue is that these vaccines have been used in an indiscriminate way across entire populations, with individuals at very low risk from the disease being encouraged, and even coerced, into getting vaccinated. As we discussed in part 1, this kind of wholesale use of these new vaccines is almost the logical conclusion of the ‘collectivist’ view of vaccine benefit against COVID-19 once we allow perceived broader societal benefits to become part of the calculation. Also, we must not forget that unlike a treatment given to someone who is ill, vaccinations are given to otherwise healthy people and so, if these vaccines are going to be ‘safe and effective’ for everyone, then they need to be not just ‘very safe’ but extraordinarily safe. This is for the simple reason that for most healthy individuals, COVID-19 is not a disease that has major risks and so the benefits from the vaccination are consequently small (vanishingly small in some cases) and so to try and make the benefit-risk equation balance for many people means having levels of vaccine safety that are almost beyond the bounds of pharmaceutical possibility. Of course, if we decide to count the potential benefits to society, we can skew these calculations, but even here these societal benefits need to be pretty large and tangible if they are to balance out even rare levels of vaccine-related SAEs.

As Professor Whitty noted in his WhatsApp message to Matt Hancock, with a disease with such low mortality “safety studies cannot be shortcut”. Yet, this is precisely what happened because one cannot do a two-year safety study or long-term follow-ups in six months. As discussed in part 1, trying to get a handle on vaccine safety post-marketing is challenging, especially in identifying and quantifying very rare safety issues. Worryingly though, rather than potentially being very rare events (occurring less frequently than 1 in 10,000 doses), reanalysis of trial data suggests that the risk of an SAE from the COVID-19 vaccines could be as high as 1 in 800 per dose, although this number is subject to some dispute. But if this 1 in 800 per dose figure is accurate then because, as we discussed above, the vaccinations require multiple doses the risk over a course of injections will be even higher, approaching a 1 in 250 chance of having an SAE over a course of three doses. In fact, in a world where every person over the age of 50 has a COVID-19 ‘booster’ every winter, if this rate of SAEs per dose was to remain unchanged, then the likelihood of having an SAE before your 80th birthday would be about 1 in 25. With these rates of SAEs, it is hard to see how it would be ethical to justify vaccinating all but the most vulnerable individuals.

Having a drug-related SAE is a bit like being involved in a major car crash in that the likelihood of this happening might be low but the consequence to the individual can be catastrophic. We need to bear this in mind when talking about SAEs and vaccine injury from the COVID-19 vaccinations: just because such events are rare or a ‘statistical tail-effect’ they are still real people, experiencing real life-changing events. Worrying about the safety of the COVID-19 vaccines doesn’t make one an ‘anti-vaxxer’ any more than worrying about the safety of cough medicines or drugs makes one an ‘anti-piller’. It recognises that people suffering from a vaccine-related SAE have as much right to a healthy life as those unfortunate enough to catch serious COVID-19. Unfortunately, ignoring safety signals does not make them go away.

How many COVID-19 vaccine induced SAEs are acceptable? Difficult to say but just because it is an awkward question doesn’t mean we should stop asking it. Perhaps the more pertinent question for today is:

How may COVID-19 vaccine related serious adverse events would it take before we decided that these vaccines have a problem?

George and Mildred are pseudonyms of senior individuals working in the pharmaceutical industry.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Excellent article by David Craig, full of useful information.

When you look at his estimated cost of £2,500,000,000 to be lavished upon hostile alien men who have abandoned their families to break into Britain and scrounge off British Taxpayers, and compare it to the UK Defence Budget for 2024, you find that the government will fund the Muslim Army by cutting the British Armed Forces budget by £2,200,000,000.

In the old days, there was a word for this. Begins with “T” followed by “reason”.

Something else which is growing, according to statistics, is street crime in London. Much like Johannesburg or Lima, wear that Rolex at your peril. Not great for attracting visitors, really;

”On March 28, Thursday, former England cricket captain Kevin Pietersen took to X to voice his concerns about the staggering rate at which street crimes in London are rising.

Resharing a post by @CrimeLdn, which had posted a video of a recent knife attack on a train in London, the cricketer labelled London as “a disgrace of a place”.

“WTAF is this now in London?!?!?! London was once the most amazing city. It’s an absolute disgrace of a place. • You cannot wear a watch of any value. • you cannot walk around with your phone in your hand. • women get their bags and jewellery ripped off them. • cars get smashed in for a quick smash and grab. • there’s this rubbing in the video below. @SadiqKhan must be really proud of what he’s created?!” Pietersen captioned his post.

Data from Watchfinder & Co. last year revealed that between 2015 and 2022, the number of stolen watches in England and Wales nearly doubled, from 6,696 to 11,035.

More than 6,000 of the thefts in 2022 took place in London.

Rowley is the representative for a region of Westminster Council that is near the Middle Eastern-populated Edgware Road neighbourhood of central London.

The borough is also home to a few of the city’s most wealthy neighbourhoods, renowned retail avenues, and many of the tourist attractions that draw in approximately 4.5 million people annually.

It is, however, also the “most dangerous” area of London, according to the CrimeRate database, with a crime rate that is 215 per cent higher than that of the entire city and 265 per cent higher than that of the entirety of England and Wales.”

https://www.opindia.com/2024/03/whats-wrong-with-london-cricketer-kevin-pietersen-raises-concern-over-spike-in-street-violence-in-uk-capital/

The Liberal Progressive virus is spreading across the western world faster than covid on speed. —Symptoms include a slight dizziness at the prospect of punishment or discipline. A brain fog when it comes to attributing blame to individuals for their crimes. Confusion and disorientation by the blaming of society for the behaviour of perpetrators of crime. Vomiting at the prospect of concern for victims. A point-blank refusal to think you need help for your condition.

That clown in the photo and his useless colleagues couldn’t run a bath.

Incompetence > Malice

They don’t become politicians by knowing wtf they’re doing. They become politicians because they don’t know wtf they’re doing.

Remember the Elephant in the room. ———-NET ZERO. ——-Net Zero is a policy designed for growth reversal. It is deigned to lower living standards. It is a policy to restrict growth. The whole idea of Sustainable Development is that the living standards and consumption patterns of populations of the wealthy west are —TOO HIGH. ——Or as Maurice Strong told us some years ago “Isn’t the only way for the planet too survive is if Industrial Society collapses, and isn’t it our responsivity to bring that about”. ——Politicians of both main stream parties speak with FORKED TONGUE.

Stuff the economy.

Let’s say we concrete over the whole country with warehouses. Fill them with cheap immigrant labour. The GDP increases. Large corporates pay their CEOs vast salaries. The tax revenue funds an even bigger administrative state.

So what?

There’s more to our way of life which you can’t price but is being destroyed by Westminster.

The policy settings conducive to high rates of economic growth are well established; low taxation, low regulation, secure property rights, and cheap and reliable supplies of energy. For the past twenty-five years UK governments have followed the opposite policies and predictably growth has slowed and has now ceased. Hunt and Sunak ought to be hanging from lampposts for their part in destroying freedom and prosperity.

I think about 620 lampposts will be needed.

The time-serving useless idiots in the Lords can just be let go.

Now an extra £1.5bn can be added that the prime minister of foreign affairs, Baron Dave of Loserville, has handed to Ukraine. Glory to UKrainia!

I think they’re running a deliberate scorched-earth policy – making it impossible for the incoming Labour Government to do anything differently – even IF it wanted to. Politics is a game to these people: they don’t give a 4X about the devastation they are causing to the lives of “ordinary” people.