Coronations used to be about the future. It was a political event, not a cultural one. The ceremonies themselves gave a beguiling foretaste of the reign to come. Here’s what Gilbert Burnet, a prelate specially chosen by William III and Mary II, preached at their coronation in 1689:

Here are the true measures of Government; it is a Rule, and not an Absolute Dominion; it is a Rule over men, and not a Power, like that which we have over Beasts. In a word, it is the Conduct of free and reasonable Beings, who need indeed to be governed, but ought not to be broken by the force and weight of Power.

This was a promise to abide by the Bill of Rights, recently drawn up, and to resist impulses to absolutism – then in vogue in the rest of Europe. Even the coronation of the late Queen Elizabeth II promised a new Elizabethan age. Its ceremonies, its meanings, had not yet been consigned to historical curiosity. Aristocracy and the ancien regime were still just about extant in the Britain of 1953, and would only disappear for good in the high tragedy of Suez a few years later.

In the run-up to Charles III’s own coronation, royal publicists have made much of the ideas of ‘old’ and ‘new’. But this is absurd. Some of the more jangling features of the old ceremony are to be discarded. We learn that Charles will not wear knee-breeches, the style of the 18th century, and will instead appear in modern military uniform, as if the latter – a creation of the Napoleonic Wars – is somehow new.

In fact, Charles III’s coronation will be the first to look explicitly backwards. It will be the first coronation with its own idea of Britain. It has been said that the ceremony will reflect modern Britain, but its components – or shibboleths – precede Charles’s reign by several decades. It belongs firmly to the mid-20th century. One planned fixture, the NHS, is a health bureaucracy, founded four months before Charles’s birth. Another, immigration, begins with the landing of the HMT Windrush that same year.

The question for this coronation is not the past versus the present, but whose past? Charles’s coronation will look backwards, but not very far. This was a tone set by his mother. We are reminded by David Starkey that for Elizabeth II the succession of her grandfather George V is a Year Zero: everything before the turn of the century may as well not have existed.

Britain’s public doctrine in 2023 has no idea of the future, or the past, or even the present. It can only celebrate the recent past, that which is old enough to be tired but not old enough to be an artefact, or a legend. It’s stuck in a rut, and is too incurious to think of something else. It isn’t surprising then that Boris Johnson, ever promiscuous with metaphor, chose to describe the Windrush as Britain’s Mayflower.

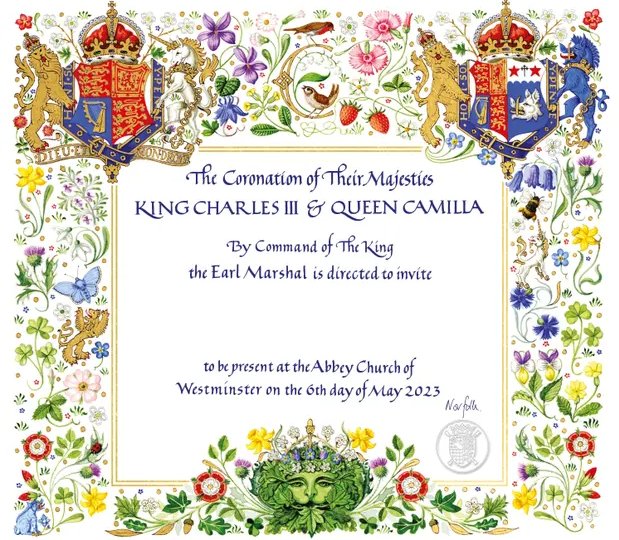

An apt symbol of this can be found on the invitation to the ceremony. At the bottom of the card is a green face, beautifully drawn. As many have identified, this is the Green Man. He is something of a historical punchline. In a famous article in 1939 the antiquarian enthusiast Baron Raglan wrote that those who carved leafy faces into buildings over the centuries were in fact carving the same fertility god, which was evidence of a low-level paganism. The idea rested on the dubious assumption that different artists couldn’t have arrived at the notion of a fantastical face independently. In fact, it soon emerged that most of the Green Men on churches and houses did not enjoy a storied antiquity, but were more or less fresh from the kiln.

The default to ahistorical kitsch is telling. Slav nationalists in the 19th century used to scrape together these kinds of knick-knacks to prove they had a history of their own. Britain never had much of a mystical folk tradition. There are no Black Forests here for wood elves, sprites, or wolves dressed as grandmothers to dwell in. We chopped them all down for firewood centuries ago. We blew railway lines through the ancient hills. We filled the magical lakes with molten slag. The island of Great Britain, and its history, is a testament to man’s mastery over nature. We created meaning for ourselves. We didn’t look for it under stones.

The alternative offered here is singularly unappealing. Look at the rest of the invitation. There is too much going on. It is overripe and fetid. None of it seems healthy. It looks like a swarm of gnats. It is rich enough to be mimetic. It doesn’t remind us of an open English field, but a walled garden, overgrown and stuffy. You scratch. You feel like you’re being bitten by something. It doesn’t imply a mastery over our surroundings, but a passive awe for its mysteries.

This is the governing spirit of modern Britain, which refuses to build any roads, or railways, or power stations, and which has artificially squeezed the city of Cambridge – which should be a science centre on par with Silicon Valley – into a sleepy East Anglian market town. It substitutes theme park kitsch for the real thing. It makes more of Morris dancing than Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. It is of a piece with Harold Macmillan’s remark that post-war Britain was now a Greece to America’s Rome, and should behave as such – this being the country that had just invented radar and computers, and built just under half the world’s ships. We are never more Americanised than when we consent to play the role of a quaint garden centre.

Judging by the then-Prince of Wales’s obscure croakings about the primacy of the spiritual over the material, this coronation will not announce any new course. Those who would prefer something different should look elsewhere.

J. Sorel is a pseudonym.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.