I want to start by making two points.

Firstly, this post is about deaths. This isn’t an abstract concept – there were real people who were alive one day and dead the next. I knew some people who died during the Covid waves in 2020 and 2021, including one very good friend, and I miss them all. I ask that readers try to bear this in mind when thinking about the concepts that I’ll explore in this post.

Secondly, I must apologise to those who lost loved ones during the Covid waves in 2020 and 2021, because this post won’t help them in their grief. Nothing that is said now will bring them back, but it could bring back harsh memories that were best kept in the past, and introduce new uncertainties that will only make the grief worse. I’d very much have preferred to not have had to make this post, but it is important that we know what has happened so that we can learn from any mistakes that were made and try to ensure that they can’t be made again in the future.

Recently there have been a few posts on the topic of the use of midazolam and morphine to hasten death during the Covid waves in spring 2020 and winter 2020-2021. Most notable are the videos made by Dr. John Campbell and the posts of Professor Norman Fenton.

These reference a document issued by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, NICE, on April 3rd 2020 regarding treatment for those suffering from Covid, and which included a section on treatment for those near the end of life. This end-of-life care centred around the use of morphine and midazolam to ease the suffering of these individuals (as well as potentially other drugs: haloperidol and lorazepam).

The question that is now being asked is whether this end-of-life treatment might have been used too hastily, resulting in the death of individuals who might otherwise have survived. It is important to note that these guidelines came from NICE – this isn’t a simple guidance for medics, but a set of rules that they have to follow unless they have good reason to do otherwise.

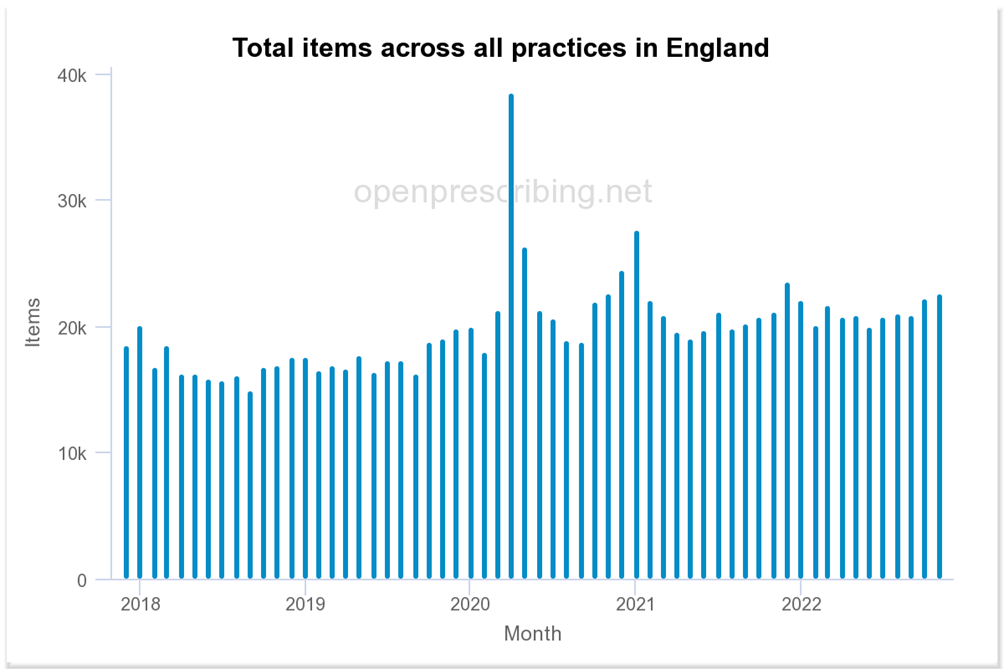

Supporting this hypothesis are data on prescriptions for midazolam by GPs over the last few years:

Particularly of note is that pronounced peak in prescriptions written for midazolam in April 2020, and a smaller peak in winter 2020-21.

Unfortunately, the graph of GP prescription data doesn’t tell the full story – there’s also the use of these drugs within a hospital environment. Data for hospital use of drugs are available here. I consider it a bit of a shame that these data are so awkward to use – almost as if the NHS was required to publish the data, but wasn’t so interested in ensuring that the public could actually see what was going on. Nevertheless, it is possible to analyse these data to identify trends in hospital use of different drugs.

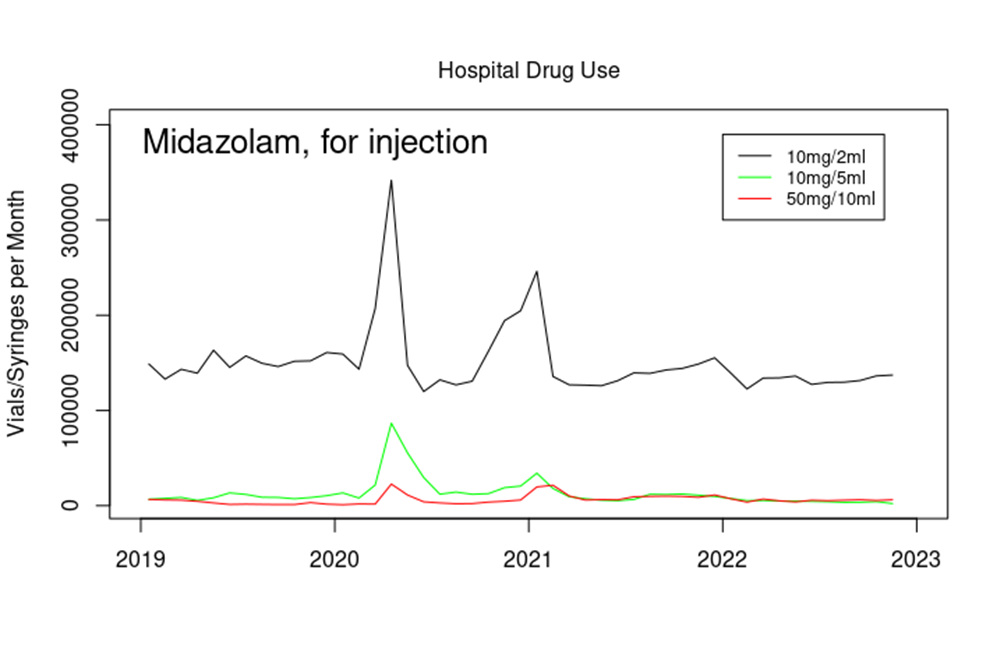

First there’s midazolam:

These data show that even in normal times hospitals use far more midazolam than GPs – compare the GPs 20,000 prescriptions per month with the near 150,000 vials per month just for the 10mg/2ml vials of midazolam. Note that they have good cause to use this drug – it is often used before surgery and other medical procedures to induce sleepiness and reduce anxiety at a time when the patient is probably, and quite reasonably, apprehensive about an upcoming procedure. NHS hospitals perform around a million surgical procedures per month, so the baseline use, while seemingly high, is in proportion to the medical need.

And, of course, note the huge peak in use in April 2020 and winter 2020-2021. For the 10mg/2ml preparation, that’s more than twice the normal usage, at 200,000 additional vials in a single month.

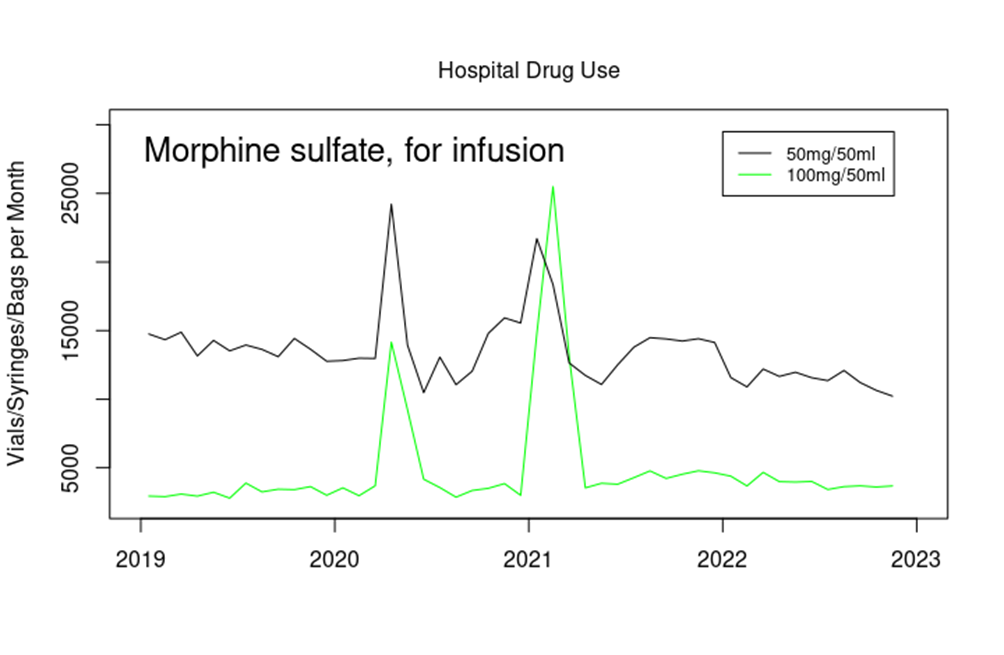

There’s a similar pattern in the use of morphine in hospitals. First morphine for infusion (i.e., introduced via a ‘drip’):

Note that morphine is also used in vials of 100mg/100ml and 250mg/250ml – these preparations are often used within hospitals but didn’t show a significant increase over this time period.

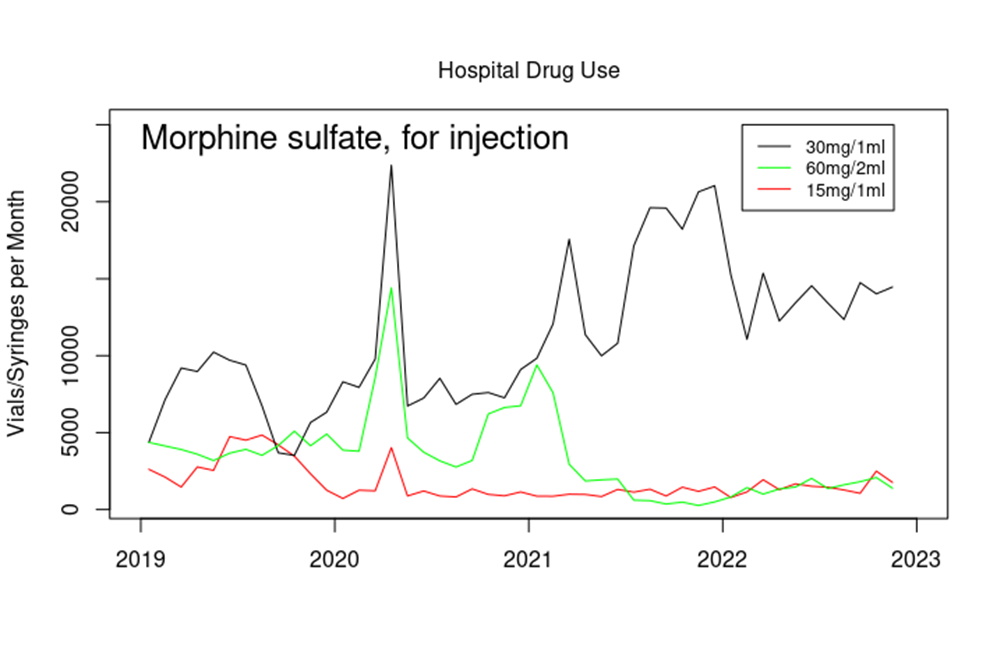

And in addition, morphine for injection:

Note that by far the most commonly used form of morphine is in vials of 10mg/1ml – at around 250,000 vials used per month this is far in excess of the quantities shown in the graph above. However, there appears to have been no similar increase in use of this preparation of morphine over the time period in question.

Again, it is important to consider that morphine is used extensively within hospitals for the relief of severe pain, and the baseline levels (including in other preparations of morphine that didn’t show a significant rise during the times in question) are to be expected. It is also important to note that drugs that have been prescribed aren’t necessarily used – it could well have been that during April 2020 doctors ‘gathered resources’ in anticipation of a problem that didn’t materialise, at least to the apocalyptic levels forecast by government ‘experts’.

I’ll also reiterate – the use of morphine and midazolam presented above is in addition to the use of these drugs by GPs, as described in recent posts by others.

Thus it appears that there was also a significant rise in the use of certain preparations of midazolam and morphine within hospitals during April 2020 and winter 2020-2021.

But what does all this mean?

It might be tempting to reason that all of these vials of morphine and midazolam were used to kill people. There are those who suggest that this approach might have been used deliberately to ‘clear beds’ in early 2020. It is certainly easy to forget that during spring 2020 we were all told that the hospitals would be overflowing with Covid patients and at that time the Nightingale hospitals were starting to get constructed (never to be used). However, I think that this particular use is unlikely. Doctors aren’t evil people (with a few obvious exceptions) and wouldn’t go along with ‘orders from above’ to commit such atrocities. Furthermore, even if there were a few psychopaths amongst their numbers, there would have been other healthcare workers around them who would have picked up on any staff who were deliberately causing death in those who weren’t otherwise at their life’s end. That said, it cannot be assumed that healthcare professionals will self-police in this way – there are occasions where individuals work alone, and there is always the suspicion that there might be a certain amount of ‘closing rank’ when criticism of behaviours is expressed (whether or not such suspicions are reasonable).

At the opposite extreme, it is possible that all of these vials were used in a genuine act of kindness, easing the suffering (but not promoting death) of individuals who were very very ill with Covid and who were clearly in their final hours of life. It is important here to point out that medics see much more of life and death than many of us would care to see. In their career they will almost certainly have to make difficult decisions and recommendations on behalf of their patients, and it is surely a heavy burden to carry. In particular, front-line healthcare staff in 2020 and 2021 will have seen patients in respiratory distress, something that they will almost certainly have found distressing themselves and they would have looked for ways to relieve this distress in their patients. We certainly shouldn’t demonise medics when they have acted with compassion, nor their instruments where they were wielded with care.

However, I fear that there is a likelihood that we have had a ‘middle ground’ – the NICE guidelines appear to have introduced a pathway for doctors which allowed for (perhaps even encouraged) more than a gentle nudge for those who were ill with Covid towards death, some of whom might well have survived given the chance. This iatrogenesis hypothesis would mean that at least some of the deaths recorded as with Covid might well have been a direct result of the care guidelines as set out by NICE – though it should be noted that the guidelines, issued on April 3rd, came close to the peak of daily Covid deaths rather than at the start of the wave, and daily deaths declined sharply shortly afterwards.

It is easy to forget now that we’re ‘living with Covid’ that there was a great deal of fear of Covid back in early 2020. The Government official line was that Covid could be a very serious disease in all and a near death-sentence for the vulnerable. Furthermore, all of the mainstream media had been co-opted to ensure that the entire population was constantly reminded of this (and had been induced into terror at the intended level) and to quash (and de-platform) any dissenting voices. This fear would naturally have affected our healthcare workers, and there is no doubt that there would have been reluctance to spend too much time with the infected, at least in those early days. What’s more, healthcare workers were instructed to limit time with the infected, to reduce the risk of themselves catching Covid or passing it on to other patients in hospital. This might have been made substantially worse by official messages of the very high case fatality rate of Covid in the early days of the pandemic. It would take a little time before healthcare workers would gain a practical understanding of the true lethality of Covid in the various vulnerable groups. Whether this fear might have altered the notion of what healthcare workers considered ethical is something which must be considered.

It is also important to consider the differences in approaches to care that you’d find in a major incident compared with normal times. Healthcare workers would have been expected to expend their efforts in saving those who could be most readily saved, with those considered to have a lower chance of survival offered what support could be spared. Thus there is the likelihood that some decisions would have been made with what might now be considered insufficient patient contact to make a full assessment of the situation. This might be considered even more likely in situations where patient assessment was given over a video link or even after verbal communication with inexperienced nursing staff. In particular, there are questions to be asked of how this policy was communicated with with care-home staff, and what safeguards were put in place to ensure that the policy wasn’t poorly applied.

It is important to note that in the iatrogenesis hypothesis it isn’t necessary for some people to have had an evil intent – it is entirely possible that individuals promoted and exercised a policy that resulted in needless deaths while believing that they were ‘doing the right thing’ (e.g., see Hannah Arendt’s concept of the ‘banality of evil‘). In particular, ‘petty bureaucrats’ appear to be readily able to think up policies without seeing the need to consider the full consequences, and when these consequences are eventually revealed will usually point to the minutes from endless meetings with other petty bureaucrats to show that they weren’t personally responsible for the policy and they were simply following process. Of course, once a framework had been decided, front-line staff might have been grateful for the guidance offered given the challenging times, at least until the negative consequences of the guidance became painfully clear.

The questions thus become: Who exactly was responsible for this approach to be taken for those seriously ill with Covid? Was there any ‘encouragement’ delivered from those in Government? What happened to any feedback or criticism of the approach from front-line medical staff or from experts in medical ethics? How was the decision eventually reached to withdraw this guidance?

It is vitally important that we understand what has happened here, not only because if mistakes were made they should never be allowed to happen again, but also because we need to understand whether there should be safeguards in place that could have prevented any mistakes from happening in the first place. If there is a need to alter the power-relationship between guidance authorities (NHS leadership, NICE, MHRA, JCVI, etc.) and medical staff then this needs to be undertaken as soon as possible. Similarly, if the mechanisms in place to allow healthcare workers to report inappropriate working practices aren’t working (or if they are working but no-one pays any attention in the end) then this needs to be rectified.

Note that the problem with healthcare in 2020 and 2021 is broader than the potential issue of midazolam and needless deaths – any investigation into healthcare during this time should certainly include community healthcare, the lack of GP provision and, particularly, the experiences of those in care homes.

Finally, we need to fully understand if the people who ‘encouraged’ this approach were actual medical personnel or if the ‘orders came from above’, made by civil servants with motives other than the well-being of those who placed their care in the hands of the NHS.

Note that this isn’t a trivial consideration, simply trying to find ‘the right people to blame’ for the mess that we’ve had over the last three years. Trust in our healthcare systems is a very important factor, something well understood over 2,000 years ago and embodied in the Hippocratic oath. We’re already seeing the erosion of trust in traditional vaccines because of politicians’ declarations of ‘safe and effective’ for the Covid vaccines which have turned out to be rather complicated beasts. If medical professionals around the world don’t grasp the opportunity to have an open and honest conversation about the mistakes that were made we run the risk of forming a serious distrust in medicine in general.

I have written before about the need for a ‘truth and reconciliation’ approach to the official Covid response. Instead our leaders appear to favour the ‘stick it out’ approach, where they steadfastly refuse to acknowledge any deficiencies in the decisions made in 2020 and 2021. As far as they’re concerned, Covid was a terrible disease that killed indiscriminately, lockdowns were necessary and saved lives, facemasks were necessary and saved lives and the safe and effective vaccines were necessary and saved lives. Unfortunately for them, science and medicine aren’t like economic theory – governments might be perfectly capable of making decisions on our country’s economy without there being an easy way to ever prove that they were wrong. However, when it comes to science and medicine eventually the truth will out. I suggest that our authorities would be well advised to consider an open and transparent review of what occurred over those two years, with encouragement given to relevant scientists and medics to come forth and discuss their experiences during the pandemic.

Amanuensis is an ex-academic and senior Government scientist. He blogs at Bartram’s Folly – subscribe here.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

No. Far simp[ler explanation: the NHS and the state murdered old people to ramp up the fear porn and justify the lockdowns. Period. Do Not Resuscitate. Remember that? No where in this article.

They still do the same today. It was similar to pre-Rona as well. Murdering old people is not a new fetish with the NHS. Neither is murdering babies.

Never allow your family or friends to remain in the NHS for any period of time, especially if they are older. You won’t see them again. And the usual excuses as uttered in the article will be used to justify the murder.

Scamdemic.

Submitting yourself to medical care has a certain element of a crap shoot to it. That’s always been the case,

I approach healthcare providers as I do any other product or service, with scepticism and fully cognisant that they’re at best not perfect and in many cases are shamelessly self serving. Some might be good some might be ok and some might be absolutely terrible,. Sometimes they know what they are doing, sometimes they are winging it. That’s life.

Where I think the problem is, is where people are forced into treatment and when the sick in hospitals are cut off from their families who can look out for them. The moment it stops being a choice is when it become really dangerous.

My expectations of anything provided by the government are very very low. All I ask is that they allow me the freedom to choose at all times. Is that too much to ask?

I have to say I believe the elderly were killed in large numbers…because of lack of care, DNR’s, withdrawal of medicine and food, overuse of the drugs in the article…whatever the reason, I believe it happened.

John Dee’s Almanac has a good SubStack on the matter….

https://jdee.substack.com/p/the-iatrogenesis-hypothesis

….this is just a few of his points….and it’s worth a read in full….

I shall just point out that a rapid guideline isn’t the same beast as a full guideline. A full guideline requires an enormous amount of effort by the best clinicians and academics in the business but a rapid guideline can be knocked out by a couple of senior bods in a few days and rubber-stamped without much thought.

The reason I’m digging about like this is that, aside from a peculiar blip last Apr – May, all cause death across England & Wales for 2020 doesn’t show any sign of a pandemic. I had taken this blip to be an indicator of a genuine first wave viral outbreak that was short and sharp.

However, my thinking has recently swung round to that short, sharp shock being due to dangerous discharge and ill-treatment of our sickest and oldest patients, who were evacuated from hospital into care homes where DNR and nil by mouth was the order of the day, along with withdrawal of medications save for dosing with morphine and midazolam in what was effectively an end-of-life care pathway (whether or not end of life was imminent). Laws forbidding visitation and autopsy ensured the saga could be quietly and conveniently buried (literally).

……We now see that the incredible surge in care home deaths during the spring of 2020 wasn’t due to COVID. This is the spike that had been camouflaged by presenting the data as an accumulated series, and this is the spike that shocked me when I unpicked the data. The authorities are going to great trouble to hide the fact that a massive surge in non-COVID death occurred within our care homes during spring of 2020

Great comment…it tallies pretty much with the attached BMJ article for which I make no apology for posting whenever this issue arises

Amanuensis: “I suggest that our authorities would be well advised to consider an open and transparent review of what occurred over those two years…”

Parliament: “We appreciate Mr Amanuensis’s well-intentioned suggestion, but the science is unequivocal: heat pumps save the planet.”

Unfortunately, this is probably right.

The government (and opposition) is doing everything it can to ensure that the situation is going to get worse.

They will be relinquishing all responsibility once the WHO take over the World.

Amanuensis, do you think you could check out the link to the following paper on PubMed:

Anticipatory prescribing in community end-of-life care in the UK and Ireland during the COVID-19 pandemic: online survey

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32546559/

And consider appending it to your article?

It’s no smoking gun, but it does seem to encapsulate the attitude of parts of the bureaucratic / medical / academic community to more liberal use of sedatives for euthanasia during the pandemic – particularly in advocating for more liberal rules surrounding administration by unqualified staff.

The cavalier approach, along the lack of consideration of the possibility of incompetence, honest mistakes or malfeasance affecting life or death decisions, is frankly horrifying, and does seem to indicate a level of potentially dangerous official groupthink surrounding the issue.

You forgot: lessons have been learned.

The questions thus become: Who exactly was responsible for this approach to be taken for those seriously ill with Covid? Was there any ‘encouragement’ delivered from those in Government?

Well for starters Witty and Valence are right up there on the list.

There was a time long ago when senior politicians and advisors carried the can when things went wrong, even if it wasn’t their fault (witness Carrington and the Falklands). Now they get gongs and plush sinecures.

Having said that, the net is slowly being formed to close in on that pair and their acolytes.

I suspect that if there was malfeasance those two played a significant hand in it, yes.

It doesn’t have to be malfeasance – just negligence is enough to condemn them. And I believe they would find it very hard to escape that charge, at the very least.

And then there’e the point of honour that things went wrong on your watch, so you carry the can – but such principles are out of fashion nowadays.

Reckless endangerment of life too.

Don’t ever forget the blatant malfeasance of Farrar, Michie, Ferguson (and many others). Farrar and Michie already appointed to the shiny new sexed up WHO with Global, unlimited powers, which our Beloved Leaders salivate in their haste to sign up to.

Autopsies?

More than one signature on Death Certificates?

Demonisation of Ivermectin etc?

Rubbishing of Vitamin D ffs?

I guarantee that those responsible for all this (and also for Net Zero) will smirk to themselves, realising that indeed, “they could get away with it” (Ferguson). And they have. Next time, turn the dial up to 11 even faster and “Shut Up! We own the Settled Science!”

Even those useless poltroons Hancock and Jeremy Isaak Hunt still preen themselves as gifted genii!

That’s a lot of words to say:

Handoncock + NHS Clowns cleared elderly out of hospital into care homes

To make beds for imminent plague

Lockdown + Fear Porn put into overdrive

So even most GP’s terrified also

Vulnerable contracted covid/flu

Treated at arms length as if plague ridden

Many contract pneumonia due to neglect

Speeded on way with Midazolam etc

40,000ish?

I’d be interested in knowing the history of this “treatment”, I hadn’t really heard of this before covid, is this standard practice or simply a new-age one world health way of doing things? Why we were intent on using such powerful analgesics and anaesthetics for the treatment of a respiratory illness, especially since there’s a risk of causing laboured breathing with these medicines is confusing to the uninitiated. I guess it’s about balance and being monitored – though how that jibes with ‘limited contact’ due to infection risk is a bit of a contradiction.

I’m presuming these were only given to those patients on ventilators, it’s surely overkill for anyone otherwise, but these are such strong painkillers and sleep aids I’m struggling to understand their justification – why the most potent? Yes we should be making them comfortable with pain meds but not to the extent it keeps them so deep under they lose the will to live in an induced coma.

I was involved in health care from 1971 to 2001 and I had never heard during that time of this kind of pain management for respiratory illness. Although since the end run is pneumonia, some slight sedation may make it more tolerable in those cases.

But maybe another aspect is being overlooked. The majority of CoVid cases were among elderly with underlying medical conditions so quite likely would already have been on some sedation or pain management – they often have bed-sores, arthritis both painful.

It may be their doses were increased, and it is quite possible to a level that would hasten death… as an act of kindness.

Yeah, fair enough, I’d never heard of it before, really does sound like a new euthanasia-through-the-back-door approach, more akin to creating Soylent Green or some other dystopian nightmare.

Fair point on the elderly perhaps already on pain management, so will have a certain tolerance. Though surely that’s unique to the individual patient, wouldn’t want to go overdosing someone on morphine who only needs a bit of codeine. Though isn’t that what end of life care is all about – being given an overdose and able to drift off and away in comfort (once you’ve decided you simply can’t take it anymore and aren’t improving)? How this is decided without any influence is the ultimate question of course.

NHS guidelines surrounding use of Midazolam and Morphene in the pandemic, such as this from NHS Scotland:

update 8 EOLC care for the covid patient final for guidelines WIH V1.docx (003).pdf (scot.nhs.uk)

Recommend use of sedatives for ‘end of life’ care in response to symptoms including anxiety. The recommended doses are fatal for elderly people. There’s no requirement for patients being on a ventilator, or even as far as I can tell, proper clinical assessment.

That sounds a lot like the Liverpool Care Pathway, a care package with the potential for abuse. No requirement for ventilator would suggest there’s little else to qualify but being elderly, frail with a comorbidity. In all seriousness that describes anyone over the age of 70. What else constitutes the qualifying process for ‘end of life’ care? If it’s simply a respiratory illness they’re expected to never recover from, that’s plain wrong in my opinion. Covid wasn’t a death sentence – despite many proclaiming it as such.

Appreciate the link.

The smoking gun was highlighted early on by the unfortunately named John O’Looney undertaker. He reported that the distribution of deaths between nursing homes and individual’s homes was completely unnatural i.e. all the deaths occurred in the homes and none in the community. Simply by looking at this distribution one can show that it was the interventions that were killing.

“deaths occurred in the nursing homes and none in the community” to be clear.

My brother, 80 years old, was in a care home with progressive vascular dementia after a stroke during the ‘crisis’. Getting information about him was difficult as nobody could visit, but we were told he was unwell but the GP would not attend as that was policy, not to go into care homes.

He was diagnosed – over the phone – as having urinary tract infection and antibiotics were prescribed.

He later, before vax, contracted Covid but recovered after about 3 days, but we were told others had died in the home as they could not be transferred to hospital.

It’s too late for a “truth and reconciliation” process. The Globalists, Big Pharma, our political class and the mainstream media have systematically lied and lied to us for 3 years …. and most in the medical profession have gone along with the lies and delivered the medical interventions they were instructed to deliver ….. knowing full well the harm they were causing to a great many people.

Trust the medical profession? In a parallel universe.

Sadly, this is probably right. Our authorities (and worldwide) had an opportunity to sort out their mistakes without looking guilty (ie, simple mistakes made in a time of fear and uncertainty) some time ago — instead they doubled down on their misinformation / obfuscation.

Even Anders Tegnell apologised for his (few) mistakes in Sweden!

Our evil barstewards? Or Fauci and Birx? Not a chance! Never!

Brings me back to the question ‘why’? Are they really that unintelligent? As you said, the truth will out.

And they had so many opportunities to be intelligent.

I now think they hope it will all go away with time. People forget, want to move on.

Yes unfortunately it’ll never happen as there’s too many corrupt scumbags who do not possess an intact moral compass invested in this false narrative. Too many egos and reputations at stake. The thing is, the more time goes by the harder it is for anyone else who was pro-narrative to do that all important U-turn and show some humility in admitting they were wrong. It’d just look entirely phony and lame, say, in 6 months time, in my opinion. Time is running out for people to search their consciences, switch sides and eat humble pie as a result. We’re not even talking just the Covid-related abuses now are we? Nothing is an isolated incident. It’s becoming more and more obvious, as we look at everything going on globally that results in the harm and control of the masses, that everything is inter-linked, therefore there’s too much at stake for TPTB and they’ll never give an inch. I continue to expect the worst but hope for the best.

I share your views entirely Mogs.

The only truth and reconciliation process that would suffice is trial by jury then firing squad.

The only conclusion I can reach from the past is 3 years is that humankind is incapable of collectively acting ethically, learning from the lessons of history, and acknowledging the truth that abides in real experience and evidence. On this amazing planet the majority are creating a hell, a dystopian faux paradise that I suspect will lead to mankind’s extinction. All in the name of saving the planet and lives. Paradise Lost indeed.

I don’t think there is anything resembling ‘human’ in the beings that enforced these policies my friend.

The fact that prescribing of these drugs seems to be increasing despite the vastly reduced impact of winter viral infections seems to indicate, to me, that this treatment is now becoming normalised within the wider healthcare sector.

Are the graphs of Midazolam and Morphine injections for the UK or just for England?

It would be interesting to see comparitive graphs for England, Scotland, Wales and NI. I remember an article pointing out that the spikes in deaths in spring 20 and winter 20/21 in England were much higher -adjusted for population size, of course – than in the other 3. It would be helpful to know if there were similar differences in the use of Midozalam and Morphine. between the 4.

During April 2020 hospitals were emptied of about half of their patients. Some returned, but on average hospitals were only 60% full across the month. The spike in prescriptions was spread across a far more concentrated bunch of patients.

‘It is easy to forget now that we’re ‘living with Covid’ that there was a great deal of fear of Covid back in early 2020. The Government official line was that Covid could be a very serious disease in all and a near death-sentence for the vulnerable.’

Yet in mid-March 2020, the WHO, closely followed by the UK government’s own specialist advisory committee, officially downgraded the cvd19 threat to the level of seasonal flu.

By doing so, it prevented medics from repurposing any drug for treatment as is written into the policy regarding high consequence disease, thus paving the way for the emergency use authorisation of the bioweapon injections. If any treatment were available, no bioweapon injection would be permitted.

All part of the overall plan.

A good point, something that I have seen suggested somewhere in the last couple of years but I had forgotten about until you mention it here.

This is actually more important than it appears. All of my interaction with doctors these days is bounded by what they are permitted to do rather than what is sensible. NICE and the NHS have very strong control of each individual doctor’s range of action. This is a very bad idea.

Not just medics. ALL NHS healthcare professionals have to adhere to NICE guidelines, even where the evidence used to support the guideline is not of the highest quality.

A case in point is from the SLT profession regarding exercises to strengthen the oral musculature following a stroke or in a neurodegenerative disease such as Parkinson’s Disease or MS. NICE guidelines, based on a review of all the available evidence, which in the end resulted in just a dozen papers with an underpowered cohort of circa 1,000 subjects & compared non comparable studies with different outcomes, stated that these exercises had no benefit. What was failed to be assessed was whether resistance exercises had any benefit. I knew from my clinical experience that resistance exercises worked to improve muscle strength & endurance where these exercises were carried out by patients who were years beyond the spontaneous recovery period of 3-6 months, one notable case was 27 years post onset. Yet I was banned from using this therapeutic strategy with my patients. Utter & total madness as it consigned many to a lifetime of artificial feeding & being unable to communicate verbally as their speech rendered them incomprehensible.

Evidence based practice sounds all fine & dandy until the evidence is collated in a fraudulent way. Therapy is a science & an art, the delivery of which is unique to each patient. Therapy is now rote by diktat, if you’re able to get anywhere near a clinician in the first place.

In the US Fauci did the same with Remdesivir; pulled from clinical trials for killing too many people!

Exactly.

Ask Wancock !!

‘Doctors aren’t evil people (with a few obvious exceptions) and wouldn’t go along with ‘orders from above’ to commit such atrocities.’

But that assumes conscious thought and decision; it overlooks autonomous response and action, just as we don’t think first before moving our fingers from a burning hot object

it overlooks the self-perceived god-like power over life and death, deeply ingrained sentiment of self-righteousness, and conceit of omniscience and infallibility in medical matters: they are ruled by ‘established practice’.

Surgeons still operated in filthy, blood encrusted frock coats kept in theatres long after germ theory and the importance of aseptic technique were known.

‘Doctor knows best! Doctor knows what he’s doing and doesn’t need to explain it to you… just keep still. If the medicine is nasty, the treatment hurting, that means it’s working.’

And it is easy to convince oneself, and others, that an apparent evil in ordinary circumstances when done for good, is not really evil.

(I speak from 30 years experience with dealing with the medical and nursing professions.)

It may shock people to learn that the Winter ‘flu season with the deaths of the weak it inevitably would bring, was not dreaded but welcomed because it cleared out the bed blockers in geriatric and psychiatric wards. And perhaps not as harsh as it sounds. These patients were in poor condition, in pain, no hope of remission, often lonely without visitors, very poor quality of life.

(And it is largely that cohort, let’s not forget, that ‘experts’ and Government were willing to risk the health and lives of our children to ‘protect’ and for whom the whole vaccination programme was introduced to ‘save’.)

The reality of doctors and nurses is not the heroic, front line, dedicated, selfless, caring individuals that is the rosey image the general public has.

All else aside, they behaved appallingly during the last three years and some still are being willing to inject infants with a product known to be of no benefit to them and with a significant risk of injury or fatality.

This “end-of-life” euphemism. We all know what happened.

“Doctors aren’t evil people (with a few obvious exceptions) and wouldn’t go along with ‘orders from above’ to commit such atrocities.”

So let’s say that the were being NICE and thought that they were doing the right thing.

*****

Stand in the Park Make friends & keep sane

Sundays 10.30am to 11.30am

Elms Field

near Everyman Cinema & play area

Wokingham RG40 2FE

………

The origins of state euthanasia go back at least to the tenure of Andrew Lansley as Health Secretary. The introduction of the so-called “Liverpool Care Pathway” (the title became discredited and was removed, but the policy stayed in effect) provided the umbrella of “palliative care” to become a means to terminate the lives of the elderly and chronically ill. It was refined into a triage system to decide who would be administered end of life drugs, resulting in a “good death” irrespective of care plans and powers of attorney.

At the beginning of the first lockdown, Matt Hancock is recorded as ordering and importing large quantities of Midazolam for the UK. Despite its labelling and instructions in French language, it was pushed out and often placed into the hands of nurses and care home staff willing to give injections. Large dosages administered in conjunction with morphine (as John Campbell makes clear) suppress respiration and exacerbate breathing difficulties associated with coronavirus. Restrictions on visiting NHS hospitals and care homes provided cover to hide the use of these drugs.

I strongly suspect that three elderly friends who died from “hospital acquired pneumonia” (three different hospitals) were given these drugs to end their lives prematurely.

A review of what actually happened during lockdown is as unlikely as those responsible being brought to account.

As I understand it, the key point about the advice from NICE, is the fact that the use of morphine + Midazolam suppressed breathing. So for a patient who had a respiratory infection and was struggling for breath it is highly likely that the effect of this treatment would be fatal. Indeed included in the NICE advice was the statement that staff shouldn’t be put off using the drugs simply because they suppressed breathing. From what I’ve read, this policy looks just like government endorsed euthanasia (or murder) of the most vulnerable members of our society at a time when families were excluded and so weren’t there to protect their loved ones. It is in a long list of criminal activity that was, and still is the response to covid19.

Amanuensis is giving health care workers far too much leeway and credence here than they warrant or deserve. I should know, I was one for many years. I saw how the first HIV/AIDS patients were treated back in the 80s and was shocked then by the frankly vitriolic cruelty and victimisation meted out to those poor souls. The same level of inhumanity and cruelty was in play this time around in the way patients were isolated and families denied access, plus compliance with the frankly insane drug treatment decisions like no antibiotics/steroids for breathlessness, only toxic remdesivir or ineffective monoclonals.. I refused to implement the Liverpool Care Pathway on more than one occasion – so was just replaced by others who did; I’m sure that would have repeated this time too with the DNRs and Mid/Morph cocktail. My mum was in a care home for 6 bl**dy years and I watched how she and some of the others were treated when they thought family & visitors weren’t looking (we were a very present, pushy and vociferous family so she was spared the worst, yet they still managed to break her leg on one occasion).Thank the gods she died a few years ago otherwise she’d be just another statistic by now. As Susan Sontag said in “Regarding the Pain of Others’:

“Someone who is permanently surprised that depravity exists, who continues to feel disillusioned (even incredulous) when confronted with evidence of what humans are capable of inflicting in the way of gruesome, hands-on cruelties upon other humans, has not reached moral or psychological adulthood.”

I’m sure Baroness Hallett’s inquiry will conduct a similar in-depth analysis and find the answers to the questions Amanuensis raises. Not.

I’d be amazed if Hallett’s Inquiry was as thorough, open and honest as Lord Hutton’s “Inquiry” into the “Suicide” of David Kelly.

And I’m quite sure Hallett will also have prepared to have evidence locked up for 70 years. (Or accidentally incinerated.)

Then there is the purchasing pattern of said drugs. You can’t prescribe and administer what you don’t have in stock. I seem to recall, there had been some large purchases of midazolam that is not supported by previous years usage to forecast requirements

Thank you for this article. I fully agree.

‘…when it comes to science and medicine eventually the truth will out. I suggest that our authorities would be well advised to consider an open and transparent review of what occurred over those two years, with encouragement given to relevant scientists and medics to come forth and discuss their experiences during the pandemic.’

I hope that relations with our erstwhile EU partners will be sufficiently cordial for representatives from the Netherlands and German health authorities to come over and give evidence to our ‘open and transparent review’ on the matter of the Euromomo mortality statistics for Apr-20 to Mar-21.

I have never heard the theory mooted that viruses recognize frontiers, but something like that needs to have happened to explain the fact that EuroMo graphs for Germany show no death hump in Apr-20, no excess mortality at all in that month, while just across the border to the West, the Netherlands mimicked the UK in having twice their usual average mortality for a period of several weeks.

What happened in Germany? Or, perhaps more pertinently, what didn’t?

Proof that cvd19 risk was officially (UKHSA) downgraded 1 week before lockdown 1 was declared:

UKHSA Guidance on High consequence infectious diseases (HCID),

updated 19-Mar-20

Extract:

‘Now that more is known about COVID-19, the public health bodies in the UK have reviewed the most up-to-date information about COVID-19 against the UK HCID criteria. They have determined that several features have now changed; in particular, more information is available about mortality rates (low overall), and there is now greater clinical awareness and a specific and sensitive laboratory test, the availability of which continues to increase.

The ACDP is also of the opinion that COVID-19 should no longer be classified as an HCID.’

Worth reading in full:

https://www.gov.uk/guidance/high-consequence-infectious-diseases-hcid#status-of-covid-19

On the 14th February 2023, Andrew Bridgen MP tweeted, “I have been supplied with lots of evidence from people who believe their relatives died due to the medical interventions brought in as a result of the Covid 19 ‘pandemic’. More questions for Matt Hancock to answer.”

Mr Bridgen is referring to the medical protocol NG163, the “Covid 19 Rapid Guideline”, issued by the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) on 3 April 2020. Allegations are circulating that this guidance was used as a trigger to euthanise elderly and vulnerable patients under the guise of ‘with Covid’ deaths thus inflating the appalling death toll in the spring wave of Covid19 in 2020.

Mr Bridgen subsequently appeared with journalist Maajid Nawaz on the 28th February to explain why he had submitted written questions to parliament requesting an investigation into these allegations.

The following is a transcript of a recording of victims families alleging that the British state, under Health Secretary Matt Hancock, authorised a policy of involuntary mass euthanasia of the elderly in care homes and hospitals using the drugs Midazolam and Morphine under the cover of ‘with covid’ deaths.

“The following voice messages you are about to hear have been recorded specifically for Andrew Bridgen MP. Following personal experiences that have affected each individual and their families, we have collectively put our faith in Andrew Bridgen to expose the Midazolam euthanasia policy currently being carried out in the NHS in the UK.

Hello Andrew, I would like to inform you that I believe my Dad was killed by the NHS with Midazolam and I have the evidence.

Hello Andrew, I’d like to inform you that I believe my Mum was killed by the NHS with Midazolam and I have the evidence. From Gillian.

Hello Andrew. I would like to inform you that I believe my beautiful Dad was killed by the NHS with Midazolam and I have the evidence to prove this, yours sincerely, Lee.

Hi Andrew. I have extremely strong documented evidence that the NHS pre planned and carried out my fathers murder with Midazolam and morphine. Thank you, Emma.

Hi Andrew. Just a quick message. I believe my father was killed by the NHS with Midazolam and Morphine using protocol NG163 and I have the evidence. Thank you, John.

Hello Andrew. My name is Carol Harmer. My Mum was murdered on the 12th of June 2020 at the Conquest Hospital , Hastings, in Sussex. I’ve got a Freedom of Information request in and found out, to my disgust, that she had been given huge doses of Midazolam and Morphine. When I tried to fight them I was told that they were working within the government guidelines and this was acceptable. Andrew, this is not acceptable, its not acceptable now and we all want justice for our family members that were murdered within this period. Many thanks.

Hello Andrew, my name is Jennifer. My Mums death was hastened by the use of 60 milligrams of Midazolam a day which shows in her medical records, Thanks, bye.

Hello Andrew, my name is Celia. I’m a retired nurse and I have the evidence to prove that my partner was killed by the use of Midazolam .

Hi Andrew, this is Stuart. I wish to confirm that my mother was murdered with one dose of Midazolam and I have irrefutable evidence to prove it.

Hello Andrew, this is Paul. I wanted to inform you I have received a letter of apology from an NHS setting admitting failings for the care of my father. I am confident that these failings, that have been admitted, hastened my fathers death through the use of Midazolam. I have the evidence.”