On April 8th 2020, we questioned whether Covid restrictions were too late to stop the bug and just in time to wreck the economy. Nostra culpa. We had not reckoned on repeated lockdowns, the patchwork of restrictions and what must be the cleverest bunch of crooks on earth. What follows is a sad tale of taxpayer rip-off based on all the evidence we could find – the ending leaves a bitter taste.

Once the World Health Organisation declared the pandemic on March 11th 2020, governments worldwide focused on measures to sustain their economies. In this article, we focus on the measures taken by the U.K. Government since March 2020, some of which are still active, and we examine the evidence of fraud. Part of our efforts is to understand the effects of human interventions during the pandemic.

Fraud is a criminal activity with the evident intent of stealing funds from the public purse by subterfuge. Fraud is different from waste resulting from poor accountancy or incompetence because the motive is different. As with all public measures, the sums invested and those stolen are estimates. We tried hard to keep the tallies of fraud and wastage separate. We may not have succeeded entirely, partly because the two are difficult to distinguish and because fraud can only be ascertained at the end of a legal process, which is still ongoing in some cases. The restrictions imposed by the pandemic hampered financial oversight, investigation and legal proceedings. For example, interviews under caution could not take place remotely.

The publicly funded aid programmes during the pandemic

On March 16th 2020, Imperial College London published Report 9: Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions to reduce COVID-19 mortality and healthcare demand. This report significantly affected what happened next: it set out that home isolation of suspect cases, home quarantine and social distancing could reduce peak healthcare demand. Despite being based on ‘inaccurate’ case numbers, the report suggested more than 500,000 people could die from the virus if no action was taken.

According to the National Audit Office (NAO), the first economic aid deployed in the U.K. was announced on the same day – March 16th. This consisted of four interventions, one each by the Ministry of Justice (HM Prisons & Probation Service), the Department of Work & Pensions (assessments for all sickness and disability benefits to be suspended for three months), the Department of Health & Social Care (provision of additional ventilators) and Her Majesty’s Treasury (business rate holidays).

On March 20th, the Chancellor announced the Furlough Scheme; three days later, the Prime Minister set out restrictions: citizens were only allowed to leave their homes for limited purposes and work from home apart from where absolutely necessary. As a result, nearly half of those in employment worked from home – many in the public sector.

On April 27th, the Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy published the Bounce Back Loan guidance. With no preexisting experience or pandemic plans, schemes that would typically take years to devise were cobbled together in a month. Covid highlighted the need for a tax system with an accurate picture of companies’ and individuals’ trading and profit levels to target support.

Since that date and until the end of July 2021, 370 further aid packages were launched for a total Government expenditure estimated at £370 billion to September 2021. Three major loan schemes: the Coronavirus Business Interruption Loan Scheme (CBILS), the Coronavirus Large Business Interruption Loan Scheme (CLBILS) and the Bounce Back Loan Scheme (BBLS) accounted for £79 billion of the spending.

Oversight of Government Covid spending: who is responsible?

From the start, public bodies such as the National Audit Office (NAO) and departments such as Her Majesty’s Treasury (HMT) were mindful of the increased speed with which schemes were launched and the potential pitfalls of expediency.

HMT developed the Bounceback Loan Scheme with the Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (BEIS) and the British Business Bank (the Bank), which the Department owns.

The loan schemes were provided by commercial lenders directly to businesses. The Government provided lenders with a 100% guarantee against the loans (both capital and interest), with a 2.5% fixed interest rate and a maximum length of 10 years. No capital repayments were due in year one, and the Government paid the interest. The Bank required lenders to undertake counter-fraud, ‘know your customer’ checks and make loans within 48 hours if more inspections were needed.

By October 2020, the NAO stated the Bounce Back Loan scheme was the leading fraud risk for the public sector due to the speed at which loans were rolled out. The removal of the usual checks allowed businesses to self‑certify their application, even after expediency was no longer needed. Because counter-fraud activities were implemented too slowly to prevent fraud effectively, the focus had to turn to the recovery of fraudulent loans.

The NAO highlighted the fraud’s extent, the required counter-fraud controls and the measures to protect ‘taxpayers’ interests. Before the pandemic, NAO estimated the level of fraud and error against the Government was at very high levels – somewhere between £29 and £52 billion annually. As a result of the pandemic responses, the NAO considered fraud levels were much higher. The lack of information about claimants and the discarding of normal processes provided fraudsters an open door.

The Public Accounts Committee (PAC) scrutinises the value for money of public spending. Its role includes taking oral evidence from Government officials and civil servants. They noted that social distancing meant regular loan checks and safety measures, such as face-to-face interviews for benefit applications were not possible, which heightened the fraud potential.

In November 2021, the HMRC reported it had blocked almost 49,000 claims before they could be paid out. Such levels led the HMRC to take tougher action on intentional fraudulent behaviour. In an FOI response, HMRC acknowledged it had set up a Taxpayer Protection Taskforce to recover amounts claimed incorrectly. The HMRC committed about 1,200 staff to post payment activities and over 250 staff to prepayment checks. The Taskforce was forecast to recover around £1 billion by March 2023, when it was due to be wound up. By the end of 2021, it had already recovered and prevented the overpayment of grants to a value of £830 million.

However, not all the fraud problems were due to haste. Lord Agnew of Oulton, former Minister of State, reported significant issues with the checks undertaken. In his evidence to the Treasury Committee on March 9th 2022, he stated that only a couple of extra days were needed for proper checks to be carried out. He described the anti-fraud side of the Bounce Back Loan Scheme as a “Dad’s Army” operation. Money was being lent to companies that did not even exist before Covid.

Agnew pointed to the lack of experience and high rates of staff turnover within the Treasury as contributing factors:

The only thing I can say to you is that the average age of a Treasury official is 29 and the turnover of staff in there is somewhere between 20% and 25% a year. They are very bright in a standard way – they went to a good university and got a good degree – but they have no life experience.

While HMT experience was notably lacking, Agnew also deemed the sheer number of agencies involved hindered counter-fraud measures: “There are about 25 different agencies reporting into multiple different Ministries. There needs to be a much more coordinated approach.”

Non-governmental Fraud

Action Fraud highlighted how the pandemic was an opportunity for fraudsters to exploit individuals concerned about their finances. These included fake government emails offering grants of up to £7,500 and access to relief funds. By July 8th 2020, 2,866 victims of coronavirus-related scams had lost over £11 million – over £16 million had been lost to online shopping fraud during the lockdown period.

Burgeoning coronavirus-related bureaucracy generated new opportunities for fraudsters to exploit the public for financial gain. For example, fake NHS COVID passes and scams affecting the NHS Test and Trace scheme were used as ruses to persuade the public to hand over their financial details.

How much was stolen from the public purse?

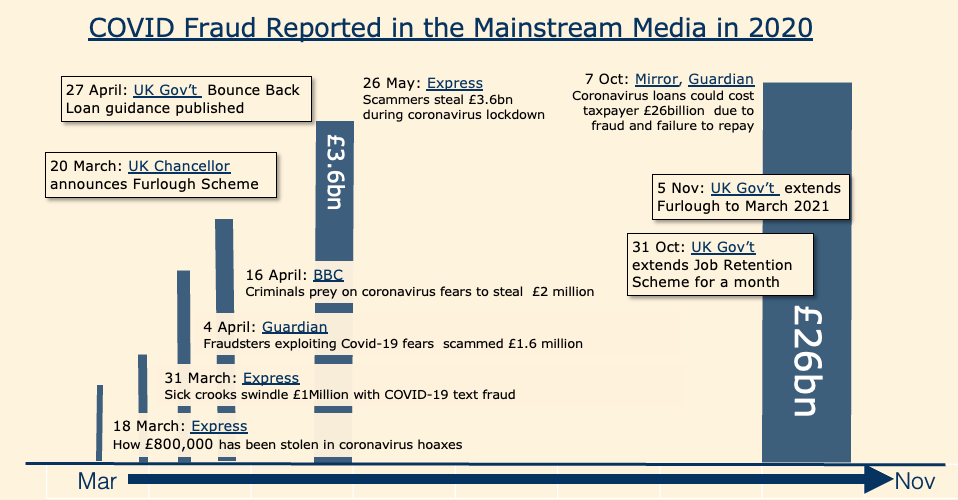

The earliest report of fraud was on March 18th 2020. In this scam, which cost £800,000, victims were offered information on who was infected in their area if they accessed a malicious website.

This type of early scam or phishing attempt was one of at least 2,500 different types reported to Action Fraud in the first month of the pandemic.

When the Bounce Back Loan Scheme went live on May 4th 2020, U.K. banks received approximately 100,000 applications on the first day. Reports suggested “the loan application took no time at all”. In August, the BBC reported that “mule bank accounts” were transferring criminal cash on behalf of others to receive the funds from fraudulent applications to the scheme. The BBC further reported that individuals’ details were stolen to apply for Government loans. Fraud investigators told the BBC, “it seems to be free money for the scammers”, and there are possibly thousands of people engaged in the fraud. Unsurprisingly, by October, the mainstream media were reporting that coronavirus loans could cost taxpayers £26bn due to fraud and failure to repay.

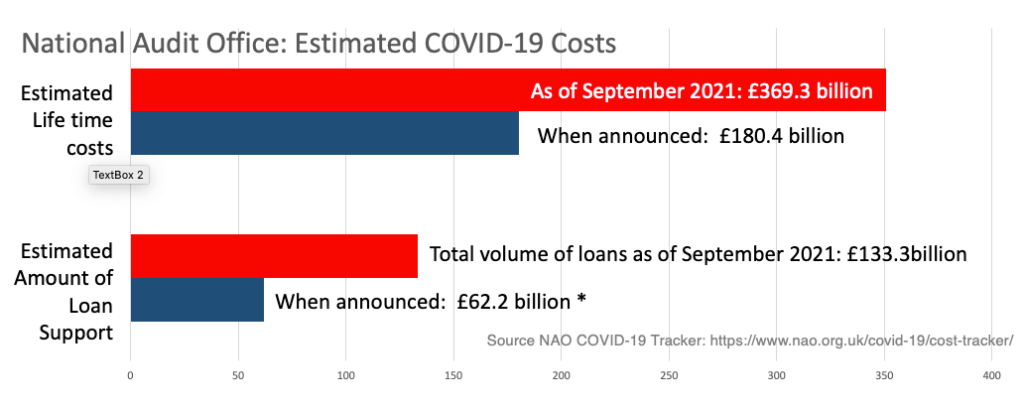

By July 2021, further warnings reported fraud and error could cost the government between £1.3bn and £7.9bn. In September, the NAO updated its cost tracker. The total estimated cost was £370bn for the Covid measures for which Government departments were responsible.

The total lifetime Covid costs for the BEIS, the HMRC and the HMT as of September 2021 were £227bn – roughly three times the additional £75 billion for healthcare costs. The lifetime cost estimates were more than double the £180 billion costs originally announced.

The NAO data on the cost tracker report 374 different financial interventions, and the amount of loan support as of September 2021 as £133bn – over twice the original estimate of £62.2bn.

The three major lending schemes (CBILS, CLBILS and the BBLS) accounted for £79bn of the loan spend. The estimated write-offs when these three schemes were announced in 2020-21 were only £5bn.

The BBLS lifetime cost is estimated to be £18.4bn, 39% of the £47.4bn loaned by September 2021. For comparison, the Coronavirus Business Interruption Loan Schemes’ lifetime costs are much lower: £2.2 billion (8.3% of the loan value), and the CLBILS, £0.36bn (6.4%).

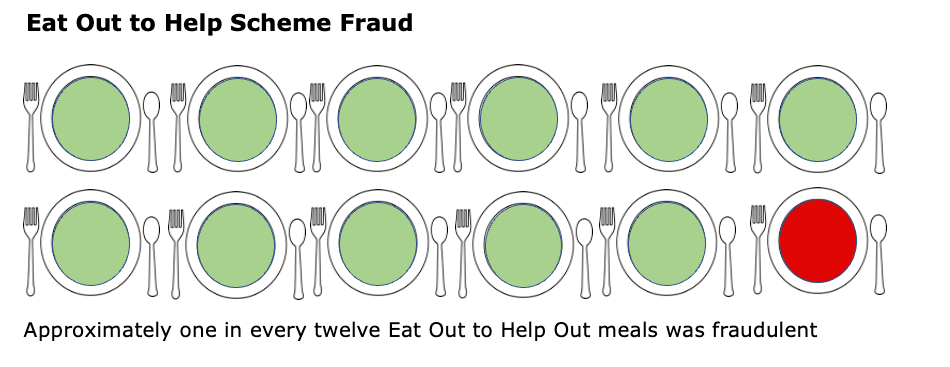

The Eat Out to Help Out scheme cost £849 million (exceeding its original £500 million estimate by 70%): 49,000 firms claimed more than 160 million meals in August 2020. Roughly 10 million people visited restaurants two to three times a month in 2018. So, either the 10 million regular eaters visited restaurants about 16 times in August 2020, or everyone in the U.K. visited a restaurant three times in that month. The August figure was roughly six times what we expected for a normal month.

The PAC estimated the scheme’s fraud losses were £71 million, almost 8.5%. We can, therefore, assume that roughly one in every twelve meals claimed never existed and was never eaten.

Towards the end of 2021, newspapers reported estimates of the total cost of coronavirus fraud varying from £5bn to £27bn. In October, Adrian Chiles wrote: “In the pandemic, £27bn worth of fraud was committed,” and asked, “Why aren’t we angrier?”

Between April 2020 and March 2021, fraud in Universal Credit rose to an all-time high of 14.5% or £5.5bn.

The PAC summary highlighted that mechanisms for managing fraud and error were in their infancy. In December, the NAO reported the Bounce Back Loan Scheme would suffer more losses than originally expected – approximately £17bn.

The lack of usual checks provided incredibly easy pickings for adept fraudsters. In November, the Daily Mail reported around 340 firms were registered to just five addresses in London, which were established on or after the furlough came into force. Also, in November, the Times reported “an alleged furlough fraudster” stole £27.4 million from taxpayers without ever setting foot in Britain by using “sham” companies. Still in November, the Mail further reported that £8.3bn (7.5% of Britain’s £111bn welfare budget) was overpaid to claimants in 2021: the majority due to fraud rather than an error.

Similar to the Bounce Back Loan Scheme, the DWP had reduced usual checks and brought in ‘easements’ that relaxed anti-fraud measures to manage unprecedented numbers of new claims during the pandemic. The PAC headlined that ‘the “DWP has ‘lost grip’ on fraud and mistakes in the benefits system”.

The chair of the PAC, Dame Meg Hillier MP, didn’t hold back with her criticism: “The Department appears unequipped either to properly administer our labyrinthine benefits system or detect and correct years of mistakes across too many of our basic state welfare entitlements, far pre-dating its current woes.”

In January 2022, the Guardian reported how the U.K. Government lost £4.9bn to Covid loan fraud, and the Mirror reported that the Treasury was giving up on chasing the £4.3bn of public cash stolen. In the same month, the BBC reported that the Chancellor – now the PM – denied “ignoring” fraudulent claims. He claimed the U.K. Government would “do everything we can” to recover fraudulent loans.

However, by February, several news outlets were reporting between £15bn and £16bn was lost due to COVID-19 fraud and error. The PAC stated that the estimated loss due to fraud and error across all COVID-19 response measures was unknown in the same month. Does anyone know what’s going on? Losses were expected to be at least £15bn across the HMRC, DWP and BEIS, about 7.5% of the total budgets.

Companies House: business incorporations and dissolutions

We analysed Companies House’s official statistics for incorporated and dissolved companies in the U.K. We hypothesised that the loan scheme may have prompted an increase in the number of companies incorporated or seen the number dissolved shortly thereafter.

Companies House incorporates and dissolves limited companies and registers company information and makes it available to the public. There are more than 4 million limited companies registered in the U.K.

We found an increase of 4.4% in the number of companies incorporated between 2017 (n= 622,713) and 2019 (n= 678,419). But in 2020, 768,777 companies were incorporated, 60,612 (13.3%) more than expected. The total number of registered companies reached 4,837,908 at the end of 2021 – 486,995 more than expected.

Dissolutions had been increasing by roughly 6%, from 470,954 in 2017 to 529,680 in 2019. In 2020 the number fell to 415,690, 146,045 fewer than expected. The numbers rebounded in quarter 4 and increased by 45% in 2021 compared with 2020, with 601,913 dissolutions. As a consequence, there were 388,847 more companies at the end of 2021 compared to the start of 2020.

Elements of the workings of Companies House may have led to delays that could have impacted these estimates. For example, the Corporate Insolvency and Governance Bill was approved with the aim of relieving the burden on businesses during the pandemic. In addition, strike-off processes were temporarily paused for one month in January 2021. Also, Brexit may have affected the estimates. However, it seems to have had a small impact on companies registering in the U.K. In January 2020, Reuters reported about 1,000 EU financial firms planned to open offices in the U.K. after Brexit.

In November 2022, the Times reported that there were at least 800 listed companies whose directors had died before the company was formed, including one named Jesus Christ. The obvious identity theft led the Times to comment that the paltry registration fee of £12 was a “facilitator for fraud on a grand scale”.

The story so far

When the decision to put severe and unprecedented restrictions was taken, governmental support for those worst affected was a sensible and humane act, regardless of the sums involved. However, because of the size of the programmes and the speed with which they were put in place, anti-fraud checks – that should have been part of the programmes – were overlooked. In several instances, they did not occur.

According to Lord Agnew, by July 2020, some 60% of the funds provided had been claimed, in the absence of the most basic checks, such as checking on the flow of funds from a company into private accounts and the state of repayments after the holiday period. It is impossible for us to say why basic checks were dispensed with, except to note that Lord Agnew disputes their delaying effect on the fund distribution times.

What makes the lack of checks seem even more reckless is the Treasury’s upfront prediction of theft levels at 5% to 10% of the worth of the various programmes as reported in the PAC oral evidence and on a background of pre-pandemic public funds fraud approaching £40bn a year. There was clearly a known landscape of ‘fraud-ready’ criminal organisations.

The lack of pandemic preparation, the Government’s appetite for hasty risk-taking fed by flawed predictions of modellers, the general media frenzy, together with the fragmentation of anti-fraud activities, created a greenhouse effect for criminals to fleece the public purse. It was all too easy; all you needed was a tenner, an email account and an address, and in an afternoon, you could have a new company and start your application to one of the schemes.

Our review suggests the total fraud losses may be as high as 10% of the £370 billion spent so far, which is £37bn. The Government’s appetite to recover stolen funds may affect this estimate, but it is close to the Chancellor’s current estimated shortfall, and a double whammy that hits the taxpayer. These estimates do not include a measure of the waste of the programs.

Activity to recover stolen funds was underway: a number of convictions for fraud (50 in 2021) have been undertaken. The HMRC expects to recover between £800 million and £1bn from fraudulent or incorrect payments. Although the figures are provisional, the funds recovered are a minuscule part of those stolen. HMRC had set up a unit dedicated to the recovery of funds. We regret to report that this, like Lord Agnew foresaw, has had a short life. Some funds are clearly more at risk of fraud than others. The losses incurred by the vast BBLS likely reflect the lack of checks required to access these funds: easy pickings for the ‘fraud ready’ and the frank opportunists.

The large-scale fraud already baked into the tax and benefits system indicated the Government requires schemes with upfront counter-fraud measures that guarantee support for those in need while protecting the taxpayer from substantial ongoing losses.

We found an increase in incorporations and dissolutions of companies. As a result, nearly 400,000 more companies were on the ‘effective register’ by the end of 2021.

Although not proof of fraudulent activities and certainly including incorporating and dissolving some legitimate businesses, the increase in years of crisis is an easy indicator for further investigation.

We require structured institutional knowledge programmes to avoid the widespread plundering of well-meaning Government initiatives. However, the key players in the current emergency will have moved on by the next crisis. This point has not been lost on PAC members and HMT officials.

Are there any measures to protect the taxpayer by paying back the predictable fraud that occurred throughout the pandemic and is still ongoing? It seems not. Only this week, Chris Smyth in the Times reported: “Benefit fraud is running at record levels, MPs warn today, part of an ‘eye-watering’ £8.5 billion of overpaid benefits last year.” Most of the problem “was attributable to the rush to pay out benefits at the start of the pandemic.”

When the PM and the Chancellor announce their tax rises next week, will anyone care to ask if they plan to claw back the massive Covid spending and subsequent fraud:? The backbenchers might want to point out that sums lost in Covid might just match the amount now asked of the taxpayer.

Dr. Carl Heneghan is the Oxford Professor of Evidence Based Medicine and Dr. Tom Jefferson is an epidemiologist based in Rome who works with Professor Heneghan on the Cochrane Collaboration. This article was first published on their Substack page, which you can subscribe to here.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

It is hard to understand the MSM culture of silence and avoidance of anything that seems like a critique of either the mRNA ‘vaccines’ or of the government health agencies, who refuse to review the collateral health damage even though informed consent and patient safety are at stake. The bodies that are meant to defend the patient and stand up for medical ethics remain quiet. The journalists, media outlets, celebrities, influencers and activists who speak out on ‘climate emergency’ or the UK getting there first on the vaccine remain deadly quiet when it comes to the greatest medical experiment inflicted on humankind” (TCW, my bold)

Not really hard to understand. I repeat my call for the Times muppets to give full disclosure on all direct and indirect links to the pharmaceutical industry. Whilst their welcome if belated story about harms from the experimental AZ coronavirus medication suggests at least some acknowledgment of the issue, they remain silent about Pfizer and Moderna, despite having a policy editor in Oliver Wright (Oliver Wright | The Times & The Sunday Times) who has written articles like these for the Independent in 2014 about unethical practices in the pharmaceutical industry, including AZ and Pfizer:

Big Pharma lobbyists exploit patients and doctors | The Independent | The Independent

Revealed: Big Pharma’s hidden links to NHS policy, with senior MPs saying medical industry uses ‘wealth to influence government’ | The Independent | The Independent

(Refresh page to show full story?)

Note particularly this section:

‘JMC Partners’ clients include blue-chip drugs firms such as Novatis, Astro Zenica, Sanofi and Pfizer. It also represents a number of medical device manufacturers and biotech companies who sell their products to the NHS, including Roche Diagnostics, Cyberonics and Bausch & Lomb.

The company’s website makes bold claims about how it has been able to influence policy. In one case study it says it represented a medical device manufacturer who was worried about a planned cut in the amount the NHS paid for a treatment with which it was involved. JMC boasted that it organised a lobbying campaign targeting MPs and ministers as well as mobilising doctors to support its cause. It concludes: “The market for the technology was saved.” ‘ (my bold)

I rather suspect that groups such as the Orthomolecular Medicine News Service (OMNS) and the Health Advisory & Recovery Team (HART) with the patient interest at heart do not have such lobbying powers. Having slandered btl commenters on this site for raising legitimate questions about the “covid ‘vaccines’ “, theTimes muppets owe us an explanation. Until they do so, and until they start behaving like proper responsible journalists, I will continue to regard them as anti-truthers. Muppets.

Not entirely unrelated to my above post, this interview with RFK Jr on the Mark Steyn show is well worth a watch:

RFK Jr runs for President :: SteynOnline

Highlights include disturbing information about the “sickest generation in American history”, how he is “anti pharmaceutical industry’s control of government”, how profit was more important than public health, and some interesting stuff on the Ukraine war.

RFK Jr and De Santis going for the “American presidency”? Now there’s a contest I could live with!

Hang it, I wish I was going on that Mark Steyn cruise…

This is just evil and sick. I sincerely hope this family get either a good lawyer to overturn the hospital’s policy or Tanner can go to another hospital where they are actually interested in saving lives.

”Tanner Donaldson, a 9-year-old from Cleveland was born with a rare birth defect that caused irreversible kidney damage in utero and has resulted in stage 4 chronic kidney disease as well as bladder and urinary dysfunctions as he grew older.

A kidney transplant from the proper donor could reverse his disease and put Tanner back on track to have a normal life for at least 20 more years. Before the pandemic began to unfold in 2018, Tanner had found that donor — his dad, Dane Donaldson.

Because a kidney from a live donor only lasts about 20 years, the family decided to wait a couple of years before carrying out the transplant to extend Tanner’s life as long as possible. Then covid happened.

Prior to the Emergency Use Authorization of the covid vaccine, Dane and Tanner could’ve undergone the surgery and be in recovery right now. But covid changed all that and the hospital is now refusing to conduct the surgery because Dane is not vaccinated against covid-19. Seriously.”

https://magspress.com/9-year-old-boy-refused-life-saving-kidney-transplant-because-his-father-is-unvaccinated/

Absolutely disgraceful isn’t it?

“Individuals who are actively infected with COVID-19 have a much higher rate of complications during and after surgery, even if the infection is asymptomatic,” the hospital stated.

Surely that should exclude all the jabbed from being donors, then?

It seems the hospital would accept an organ from a soon-to-die / brain dead individual – jab status unknown – but won’t accept from a healthy unjabbed donor.

Not only crazy, it’s bordering on evil, denying someone a chance of life.

Don’t know where the links from the word ‘surgery’ came from.

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-12077475/Starbucks-manager-sacked-transphobia-rant-activist-terrifies-neighbours.html

Why is it that people who demand tolerance and understanding have no concept of tolerance or understanding?

What ‘rights’ don’t the transpeople have that others have?

What do they realistically want?