On September 5th, Putin turned off the Nord Stream 1 pipeline – Europe’s main source of Russian gas. It would not be turned back on, the Kremlin announced, until the “collective west” lifts sanctions against Russia.

With the exception of Viktor Orbán in Hungary, Zoran Milanović in Croatia, Western leaders have shown no interest in lifting sanctions. So Europe will have to make do without Nord Stream 1 for the time being. This is not going to be easy.

In the long-term, Russian gas can be replaced with gas from other sources, or with other forms of energy. But in the short-term (the next 1–5 years, say) Europe will simply have to use less gas. As analyst Sarah Miller noted back in March, “Europe imports more pipeline gas from Russia than the entire LNG export capacity of either the US or Qatar”.

Less gas, of course, means higher prices. In the U.K., around 40% of electricity comes from burning gas. And the fact that we don’t import much from Russia is irrelevant. Britain buys gas from the international market, where prices have spiked due to lack of supply from Russia.

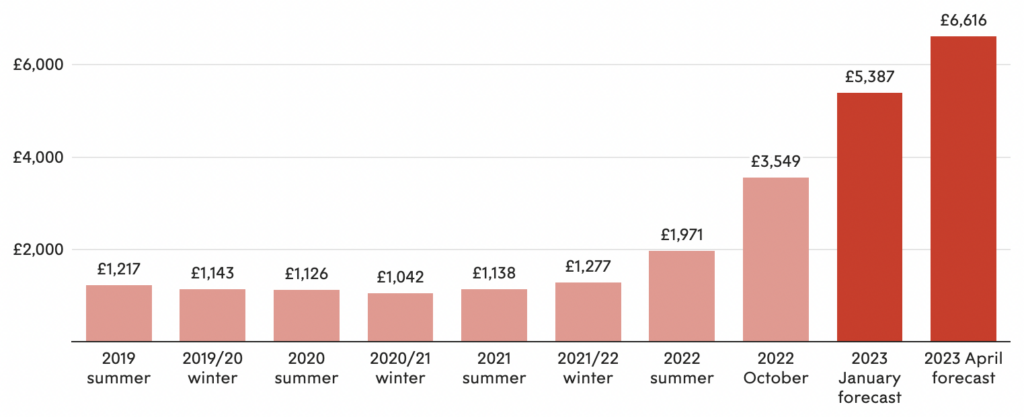

It was recently forecast that, by April of next year, the average British household would be paying six times more for energy than they had been two years before – over £6,000 per annum.

In response, Britain’s new Prime Minister, Liz Truss, announced that prices would be capped at £2,500 per annum for the next two years, along with “equivalent” protection for business. This bailout will cost an eye-watering £170 billion – about 5% of GDP or what Britain spends on the NHS each year.

Yet critics have panned the idea, which does little to address the root cause of the crisis: scarcity. In the absence of Truss’s price cap, households would have a strong incentive to conserve energy, since they’d be facing the full market price. But now that incentive is far weaker.

By April of next year, households will be paying only 40% of the cost of their energy bill – with the rest being covered by the taxpayer. Of course, households and taxpayers are mostly the same people. Which reminds one of Frédéric Bastiat’s description of government as “that great fiction by which everyone tries to live at the expense of everyone else”.

This isn’t quite true, however, as Truss plans to borrow the money. So what’s really happening is that younger Britons are footing the bill for older ones – via higher future taxes.

And because Truss’s price cap removes much of the incentive to economise, it not only burdens taxpayers with more debt, but markedly increases the risk of blackouts.

There’s another snag. If we get a particularly cold winter, market prices could go even higher – putting the government on the hook for much more than £170 billion. As analyst Javier Blas notes, “the UK Treasury effectively took the biggest short position ever in the gas and electricity wholesale markets, without a hedge”. Was it the right move? “No, no, no,” he says.

A better proposal would be to leave the energy market intact, while providing financial support to households and businesses. This way, there’d still be a strong incentive to economise.

Liz Truss likes to model her outfits on Margaret Thatcher, but she appears to have modelled her energy policy on John McDonnell. (The self-described “socialist” has called for strict price controls on energy.) Will Truss turn out to be another Prime Minister, like Boris, who pays lip service to the free market, while doing her best to undermine it?

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

“Who put the toddlers in charge?

..people who have never been told ‘no’ a…The rot began with the green lunatics”

This article seems to suggest issues are recent yet the erosion and removal of boundaries starting decades ago would have a greater influence such as changes in school discipline and the relationship between parents and teachers, relaxation in censorship of sexual and violent media content, encouraging use of credit cards (debt) to get what you want etc.

Having people behave like toddlers provides a justification to those who consider themselves the adults to take control.

As commented in an article yesterday, people need to be responsible for themselves. That includes not succumbing to propaganda and being manipulated into behaving irresponsibly just because you are led to believe anything goes.

Madness Felling Trees For Wind Farms – latest leaflet to print at home and deliver to neighbours or forward to politicians, media, friends online.

What’s really going on?

Russian seven point ‘peace’ plan:

Ukraine’s recognition of its military defeat, complete and unconditional Ukrainian surrender, and full “demilitarization”;

Recognition by the entire international community of Ukraine’s “Nazi character” and the “denazification” of Ukraine’s government;

A United Nations (UN) statement stripping Ukraine of its status as a sovereign state under international law, and a declaration that any successor states to Ukraine will be forbidden to join any military alliances without Russian consent;

The resignation of all Ukrainian authorities and immediate provisional parliamentary elections;

Ukrainian reparations to be paid to Russia;

Official recognition by the interim parliament to be elected following the resignation of Ukraine’s current government that all Ukrainian territory is part of Russia

The adoption of a “reunification” act bringing Ukrainian territory into the Russian Federation; and finally the dissolution of this provisional parliament and UN acceptance of Ukraine’s “reunification” with Russia.

https://t.me/medvedev_telegram/464

Good luck with that…….

Meanwhile, in other news……

‘…..elements of the all-Russian pro-Ukrainian Russian Volunteer Corps (RDK) and Freedom of Russia Legion (LSR) continued attacks on Russian border settlements, primarily Tetkino, Kursk Oblast and Kozinka and Spordaryushino, Belgorod Oblast on March 14

LSR forces conducted a low-altitude helicopter landing near Kozinka.

A prominent Russian milblogger criticized the Russian military command because Russian border regions cannot “breathe free” in the third year of the war and claimed that “someone” committed a “strategic miscalculation” by deciding to withdraw Russian forces all the way back to the Russian border when withdrawing from northern Ukraine in the first months of the war, making the border the frontline.

The milblogger called for the Russian military to implement “corrective measures” that would somehow push the frontline at least 40 kilometers from the Russian border and into Ukraine.

Another milblogger criticized Russian forces for not establishing barricades in certain border settlements to prevent attacks from Ukrainian territory.

These criticisms highlight the Kremlin’s current dilemma in light of such cross-border incursions.’

Remind me, just how effective was the Maginot line, exactly?

What is Macron up to?

Meanwhile Macron has been making statements about the possibility of French troops in Ukraine;

https://www.france24.com/en/france/20240314-%F0%9F%94%B4live-macron-interview-after-uproar-ukraine-ground-troops-comment-france

What sort of a game is Macron playing? Is he simply saying that the West now only has 2 options;

Maybe as he is coming to the end of his last term as French President he wants to establish his position in history?

He has lost control of the National Assembly so is searching for something to do……..

I’m not sure anyone takes him seriously any longer.

‘The West’, in fact the U.S. and Germany are the two key players, are simply intent on a stalemate.

That strategy seems to be going well, if only as a consequence of Russian military incompetence:

‘The current Russian offensive in the Kharkiv-Luhansk sector, by contrast, involves attacks along four parallel axes that are mutually supporting in pursuit of multiple objectives that, taken together, would likely generate operationally significant gains………Russian tactical performance in this sector, however, does not appear to have improved materially on previous Russian tactical shortcomings……’

He has a Napoleon (aka short man) complex.

Like Zelensky, Sunak, Tiny Tatar Putin, and a whole host of other petite world leaders, male and female. Odd, that.

P.S. Today’s Matt cartoon on the front page of the Daily Telegraph:

https://twitter.com/MattCartoonist/status/1768330966748086666?ref_src=twsrc%5Egoogle%7Ctwcamp%5Eserp%7Ctwgr%5Etweet

The Germans simply went round the line. The Russians wouldn’t have the Belgians interfering like the French did.

True.

On the other hand…….

‘…..the all-Russian pro-Ukrainian Russian Volunteer Corps (RDK) and Freedom of Russia Legion (LSR) continued attacks on Russian border settlements, primarily Tetkino, Kursk Oblast and Kozinka and Spordaryushino, Belgorod Oblast on March 14’

Time spent on reconnaissance etc. etc.

They are reported to have been comprehensively defeated with 1500 casualties and substantial armour losses. The Russians have moved civilians out of the affected villages and are now stationing troops in force.

The sad and unneccessary attrition of Ukrainian manpower and Russian traitors continues apace.

You mean these reports?

‘Democratic Russian forces are promising a mass strike against imperial military objects in Belgorod within an hour.

The “green corridor” established yesterday expired at 7AM local time this morning.’

10:38 am · 15 Mar 2024

·

No

You mean like this military target in Belgorod.

Also in today’s news Queensland tells Long Covid people they’ve got post viral syndrome but the UK long Covid grifters disagree. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2024/03/15/doctors-no-such-thing-as-long-covid/

The Telegraph article seemed very familiar.

“When people ask me about my views on long Covid, my standard answer has been that I don’t think it’s any different from post-viral syndrome”

From “Covid: Why most of what you know is wrong” by Sebastian Rushworth 2021.

“Man driving ‘runaway’ electric Jaguar arrested a week later”

Ah yes, so he (probably) was just a virtue-signalling attention seeker. And looking for an easy way of disposing of his expensive electric boondoggle, it seems.

He should have followed the excellent example of the Finns, who packed a Tesla with dynamite in a quarry and blew it up. Great stuff!

Insane Tesla Model S EXPLOSION!! 30kg of dynamite! (youtube.com)

tells us:

So, wait until they can’t be voted out before betraying the people. Let’s hope the EU voters remember this at their elections.

Reveals exactly what technocrats and bureaucrats think of the popular vote: a nuisance to be endured and quickly ignored.

There’s the rub – how do you judge what is opposed to fundamental values when Britain now recognises no fundamental values, apart from the claim that it is tolerant of all opinions and cultures, a value Gove intends to diminish.

Yes, only the CONservatives can save us from outright tyranny. Oh, hang on…

Don’t know about anyone else, but I’m sick to my back teeth of being treated like an utter damn fool who’s incapable of understanding they’re having the p*ss taken out of them.

I don’t understand what you mean. I don’t have access to the entire Spectator article, but from the first couple of paragraphs, it seemed perfectly sensible to me. What am I missing here?

https://petermcculloughmd.substack.com/p/why-c-19-vaccines-dont-prevent-infection : The fundamental con is that the definition of “vaccine” has been changed, perhaps to exploit the common belief that they prevent infection by whatever. In reality, all this product can do is to mitigate the symptoms, if infection happens.

It may well be that improved understanding of other ways to improve the operation of the immune system to do a proper job in the first place is safer and more effective – but less lucrative in the pharma trade perhaps.

Of course, there have been many attempts at excessive intervention into human rights based on that.

My respect for Claire Fox is growing.

Her ‘battle of ideas’ is a brilliant conceit, encouraging debate on all topics.

The Mayor of Tower Hamlets has bowed to pressure and ordered the removal of Palestinian flags from council buildings and lampposts, reports the Jewish Chronicle.

However they have been flying in LB Neham for weeks. When the Council was finally persuaded to act they were removed and promptly replaced. These are high enough on lamp posts that commercial grade equipment would have been necessary to fit them. Being on bust roads it cannot have been done in secret.

The latest iteration has them on a principal route intp East London – Romford Road.

“British countryside can evoke ‘dark nationalist’ feelings in paintings, warns museum”

Oh, just f*ck right off.

“Why COVID-19 vaccines don’t prevent infection”

That’s what the former President of Haiti thought, too, and refused forced covid vaccinations for Haitians.

“In the wake of one of the most devastating moments in Haiti’s arduous history, there has been a bright spot.

One week after Haiti’s president was assassinated, the country’s first shipment of COVID-19 vaccines finally arrived.

President Jovenel Moise was shot a dozen times in his private residence on July 7. Despite the political chaos, social disruption and a national “state of siege” that followed the killing, Haiti has now launched a mass COVID-19 immunization drive for health care workers and people over age 65. Haiti is one of the last countries in the world to make the vaccine available.”

Haiti Begins First Mass Vaccination Campaign Amid Rising Violence And Poverty : Goats and Soda : NPR

You may remember that the President of Haiti was one of five African leaders who opposed mass covid vaccinations of their people, and either died or were assassinated not long after: Jovenel Moise of Haiti, John Magufuli of Tanzania, Hamed Bakayoko of Ivory Coast, Ambrose Dlamini of eSwatini, and Pierre Nkurunziza of Burundi. All replaced by leaders who welcomed mass, even forced, covid vaccines.

“Is the CofE about to say sorry for Christianity?” – In the Spectator, William Moore reacts to a report by the Church of England’s Oversight Group declaring that the Church should say sorry, not just for profiting from the evils of slavery, but for “seeking to destroy diverse African traditional religious belief systems”.

And here is an example of those “diverse African traditional religious belief systems” in action today:

50 Dead After ‘Anti-Witchcraft Rituals’ in African Country (infowars.com)

“There are no laws concerning witchcraft practices in Angola. If individuals are suspected of sorcery, they are compelled to consume a poisonous herbal concoction known as ‘Mbulungo’. If they die as a result, it is considered to be proof of their guilt.

Last month, suspected death-cult leader Paul Mackenzie was arrested for the alleged murder of hundreds of his followers in Kenya. They had committed suicide due to Mackenzie’s preaching that they would encounter Jesus by starving themselves.”

Tommy Robinson is a fu£#king star!