It was with some bemusement and not a little wry humour that I read in yesterday’s Guardian of the outraged reaction among a certain class of ‘progressive’ legal activist to a leaked Ministry of Justice document which is purported to suggest that the Government is seeking to further limit the scope of judicial review, after having already legislated to do so (making it slightly harder for tribunal decisions in immigration cases to be appealed) earlier this year.

Judicial review, for the uninitiated, is in a nutshell what happens when a court ‘reviews’ the decision of a public body (such as the Government), traditionally to ensure that said decision was made through a lawful process, and more recently to ensure it was consonant with human rights law. It is a significant element of what is called ‘administrative law’ – you can think of this as being the branch of law which keeps public bodies honest – but it has always been an important constitutional principle that judicial review should be kept within fairly tight bounds. It is not to be used to challenge the substance of a public body’s decision; rather, it is only supposed to challenge a decision on the basis of it having followed an unlawful procedure (because, for instance, it was biased, or because the person making the decision did not actually have the power to make it). The Human Rights Act 1998 muddies the water here a little by giving courts the power to declare decision as being incompatible with human rights law, but what I have described is the basis of the traditional scope of the practice.

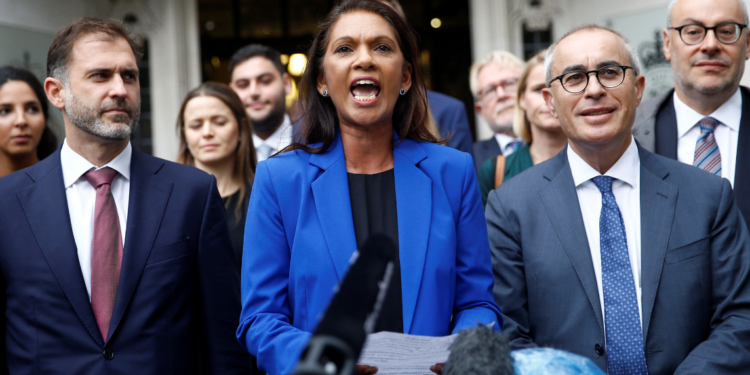

No sensible person would suggest that courts ought not to have a role in restraining the executive in this way, or in preventing serious breaches of fundamental rights, and for a long time a modus vivendi prevailed in which Government and the judiciary engaged in a careful dance in which each respected the other’s institutional role. The problem is when judicial review began to be used tactically in order to frustrate the democratic process. This happened most famously, of course, in the ‘prorogation’ case of R (Miller) v The Prime Minister in 2019. But the truth is that ‘Miller 2’, as it has come to be known, was really just at the end of a long line of judicial review cases in which the likes of Jolyon Maugham, Leigh Day, Liberty, Gina Miller and the Guardian itself used judicial review to further essentially political ends – from embarrassing the royal family to undermining Government social policy to the earlier attempt at stymying Brexit.

The capacity for human beings to fail to think through the long-term consequences of their actions is of course frequently observed; it never ceases to amaze me just how bad legal campaigners in particular are in this regard. What is so surprising, or outrageous, in the discovery that politicising the judicial process turns out in the end to have political consequences? The result of deploying judicial review as a weapon of political struggle, as has happened in recent decades, was always going to be that the courts would end up having their wings clipped. Even at the time the judgment in ‘Miller 2’ was handed down, while the media and political establishment were swooning over Brenda Hale’s spider brooch, wiser heads were warning that if the courts were going to stand in the way of a Government with a democratic mandate there would only be one winner. And so it has now proved: the Tory party is now clearly of the view that the judiciary needs to be put back in its box, so to speak, and the legal activists only have themselves to blame.

This is a deeply regrettable turn of events for two reasons. The first is that it has led judges, seeing the way the wind is now blowing, to ‘overcorrect’ and become almost obsequious in their deference to government and Parliament in recent cases. There is no doubt, for example, that fear of confrontation with government and concerns about the political backlash to Miller 2 contributed to the courts’ almost supine approach to the biggest interference with civil liberties in the nation’s history in 2020. The second is if anything more serious: it will undoubtedly result in the further politicisation of the judiciary. If the perception grows that there is a rift between the Conservative Party and the courts, judges’ decision-making will only be further warped by concerns about the political consequences of their judgments. This will mean either bending over backwards to avoid conflict, or growing more confrontational rather than less. The ultimate long-term consequence of that, one fears, will be American-style political appointment of judges, with politicians determining that if courts are going to be used as a political weapon, they should at least ensure that it is allied judges who have their fingers on the trigger. One only needs to cast a glace across the pond to see where that road leads, and it isn’t anywhere good.

Dr. David McGrogan is an Associate Professor at Northumbria Law School.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Well, be careful what you wish for. Some of us at least were cheering for Simon Dolan when he brought a case against lockdowns, which seemed strong to me (and to Lord Sumption and Francis Hoar QC, who are more qualified than I am).

Obamacare looked like an unconstitutional overreach by the US Federal Government that should have been struck down had the US Supreme Court not been at the time packed with activist judges. It would almost certainly be struck down now.

There’s a balance to be struck – our sovereign parliament locked us up with consent manufactured by advertising paid for by the taxpayer.

I didn’t let anyone lock me up. Nor did most people I know (despite many of them claiming complete adherence to both the letter and spirit of the “guidelines”).

Although it did feel at the time as if convention could be shifting enough for my neighbours to denounce me to COVID Marshalls for simply leaving my house, it didn’t happen. And not once did I break any actual laws by merely going about my normal life, unmasked, unjabbed, unrepentant – if at times somewhat angrily! Indeed, the law of this land supported me in that and it still does.

What is it that brought an end to the restrictions and a return (not quite complete, sure) to the convention of pre March 2020 in this country? In this case, I am not sure it was any legal process. No, it was the inertia of life itself. Bills must be paid, baths must be filled…

I know for a fact that plenty of people had gatherings that were illegal by my reading of the various statutory instruments in place, and of course whatever you or I did we could not unclose shops etc.

The restrictions ended for a combination of reasons, including as you say inertia of life, also protests and it would appear some kind of belated application of common sense and love of freedom from the Tory backbenches and possibly the odd cabinet minister.

I would have been quite happy to see the SIs declared illegal by the courts, though happier to see them seen off by mass non-compliance. But I think the courts have a role to play.

You know a better or more honest class of person than I do – most people I know were super compliant and are vaxxed and a lot of them I am now estranged from – mutual loathing and lack of respect.

I will never throw an ice cream at anyone!

“One only needs to cast a glace across the pond …”

‘… the courts’ almost supine approach to the biggest interference with civil liberties in the nation’s history in 2020. ‘

Odd. I saw that as quite in-keeping with the Co-tyranny that the judiciary has become. They weren’t being timid, they were all for it!

Precisely.

If the Government had created SI Regulations to force “life as usual” with shops/cafes/schools/leisure centres etc required to remain open and people encouraged to mix and spread the virus to build natural immunity, I bet the judicial activists would have done everything they could to overturn them….. using the HRA if they could.

The failure of the legions of Human Rights lawyers to challenge the Government over its draconian and unjustifiable Covid Regulations had nothing to do with concern about challenging the Government and everything to do with the fact that they are all Lefties who believe in Big Government and “the end justifies the means.”

Oh, and they’d probably have got no Legal Aid.

They aren’t freedom warriors; they’re leftwing activists. And it’s about time their wings were severely clipped. Unfortunately, the Government hasn’t got the guts to do the job properly by scrapping the HRA and leaving the ECHR.

Be careful what you wish for! That HRA is what protected Dr Sam White from losing his medical licence, specifically freedom of speech. It was this clause which the Judge referred to.

It’s all a question of balance.