Rod Driver’s recent piece was interesting but perhaps in black and white rather than shades of grey. There is, to be sure, overenthusiasm for new drugs, and occasionally concealment of risk, but the situation is more nuanced than he sets out.

In my medical career of nearly 50 years, 28 as a consultant rheumatologist, I have taken a great deal of notice of drugs – which is hardly surprising, as I have used many. As a trainee I was fascinated by the sharp dissection of a series of trials of anti-inflammatory drugs made by one of my friends. He outlined a long series of faults, ranging from inappropriate comparators, poor trial construction, inappropriate dosing schedules and use of the wrong statistical analytical tools. In my book “Mad Medicine” I have described some of these, with a specific personal episode illustrating how data can be ignored.

In 1982 I went to a company symposium abroad launching a new drug; this was not the ill-famed Orient Express trip, but much gin was tasted, as the meeting was in Amsterdam. This may not be quite as bad as it looks, because it was cheaper to fly all the British rheumatologists to Amsterdam than it was to fly the much smaller number of worldwide experts to London. The pharmacodynamics of the drug had been tested on, I think, eight normal subjects. Seven were very similar in terms of the plasma half-life. The eighth was quite different. In the presentation the pharmacologist blithely told the audience that the outlier had been ignored in the analysis of the data. I got up and asked how it was scientific to exclude over 12% of the sample; perhaps the wayward subject had some genetic difference that meant he metabolised the drug differently. He couldn’t possibly assume that this one was unique and, if they had done another hundred tests, who was to know whether another 11 subjects would have produced the same result? Much muttering and harrumphing went on. I ignored the rest of the programme and went sightseeing. You cannot analyse only the data that fit your model, and similar selective data manipulation has been exposed in other large-scale trials. I am a fan of Ben Goldacre’s book “Bad Pharma”, but it’s not just the industry that’s to blame; I wonder when the clinicians who misuse data on statins (and are often funded by the industry, so have a conflict of interest) will finally be brought to book. But to damn the pharmaceutical industry as a whole is risky. The baby may well go out with the bathwater.

Rod asks why we don’t learn the lessons of preliminary data being overtaken by new evidence, so that we realise drugs may do more harm than good. Actually this is a matter of scale. Drug trials have many phases; animal testing (though animals may develop side-effects that humans do not, and vice-versa); pharmacodynamic studies that look at how a drug may be metabolised, as above; trials on volunteers; small-scale trials on patients; and finally larger scale trials. But if a drug has, say, a serious side-effect that occurs in one in 100,000 a standard trial will not attribute it. If you get 200 people who develop it, such that you might become suspicious, you will have exhibited it in 20 million patients. You cannot do a trial that big, so serious but rare side-effects will only come out in the wash much later.

Furthermore, the initial trials may have used the wrong patient cohort. Thus benoxaprofen, known as Opren, was never tested in the over-65s, which is where in the end the serious renal side-effects appeared because, surprise, older people metabolised the drug more slowly, so it accumulated. Phocomelia is a rare phenomenon, and appears at random, but it required many pregnant women to have had thalidomide, and then (as it was pre-internet) several unconnected case reports, to attribute effect to drug. If you weren’t pregnant then obviously that effect did not appear. The use of radiotherapy in the 1950s to treat a spinal condition, ankylosing spondylitis, was found to provoke leukaemia, but this did not appear immediately. In fact, a re-analysis I did suggested that many of those who developed it may well have been treated too late and with the wrong diagnosis. Thalidomide would have been abandoned anyway, because it produced significant peripheral nerve damage, and radiotherapy caused multiple skin cancers in the X-ray field which would have proved enough to finish radiotherapy as a treatment. But if something turns up that is unexpected then the only way you find it is, if you like, to suck it and see. And you may have to do much sucking to establish a causal relationship when the side-effect is rare.

We do learn from the lessons. After thalidomide and benoxaprofen, among others, drug trial regimes were tightened up; patient cohorts were changed; statistical analysis was improved. But now and again something will slip through for reasons only understood by using the infallible instrument of the retrospectoscope – the volunteer trial of TGN-1412 is a case in point. There were errors in conducting the trial, not least that all the subjects had the drug administered together, but no-one could have predicted the side-effect (multiple organ failure). However, once the details were known, anyone who had seen that constellation of symptoms and signs – as I had once – could have been in no doubt why it happened. And so subsequent trials were adjusted to avoid the risk.

Next – patents. There is no doubt that patents are a form of protectionism, but their existence is protean and I cannot see any reason for any sector of manufacturing industry not to use them, unless they are altruistic fools. The cost of developing new drugs is immense and while trials may be conducted by hospitals and university departments it’s the industry, by and large, that funds them. People do not realise that companies must take into account both the development costs and manufacturing costs. The development costs are skewed because a large number of compounds never reach the market because something goes wrong; they may not work, they may work no better than existing drugs, they produce early side-effects and so on. All these costs have to be written into the price of the drugs that get through all the hoops and reach the marketplace. And the manufacturing costs for some of the immune therapies are huge. Would you, as an entrepreneur, be happy to spend millions in development and initial production for some other company then to pirate your hard work? And anyway, patents expire eventually. People imagine that then the drug cost falls like a stone. Actually often it does not. There are many examples of drugs no longer made by their originators because it’s not worth their while. A series of generic manufacturers jump aboard, and then discover that it’s not worth their while either; maybe the profit is inadequate or the market too small. You then get left with a single generic maker who hikes the price. They may get their comeuppance, but there have been numerous examples of one monopoly replacing another.

Do companies try to charge as much as they can get away with? I am sure they do sometimes, but I was involved with the introduction of a new biologic agent for inflammatory arthritis which was priced well above its competitors (it had a different mode of action, so was not a ‘me-too’ drug). I pointed out that this created a financial disincentive to prescribing, and notice was taken.

So I think that drug companies are entitled to protect their investment, not least because their ‘profit’ covers the cost of the myriad preparations that don’t make it.

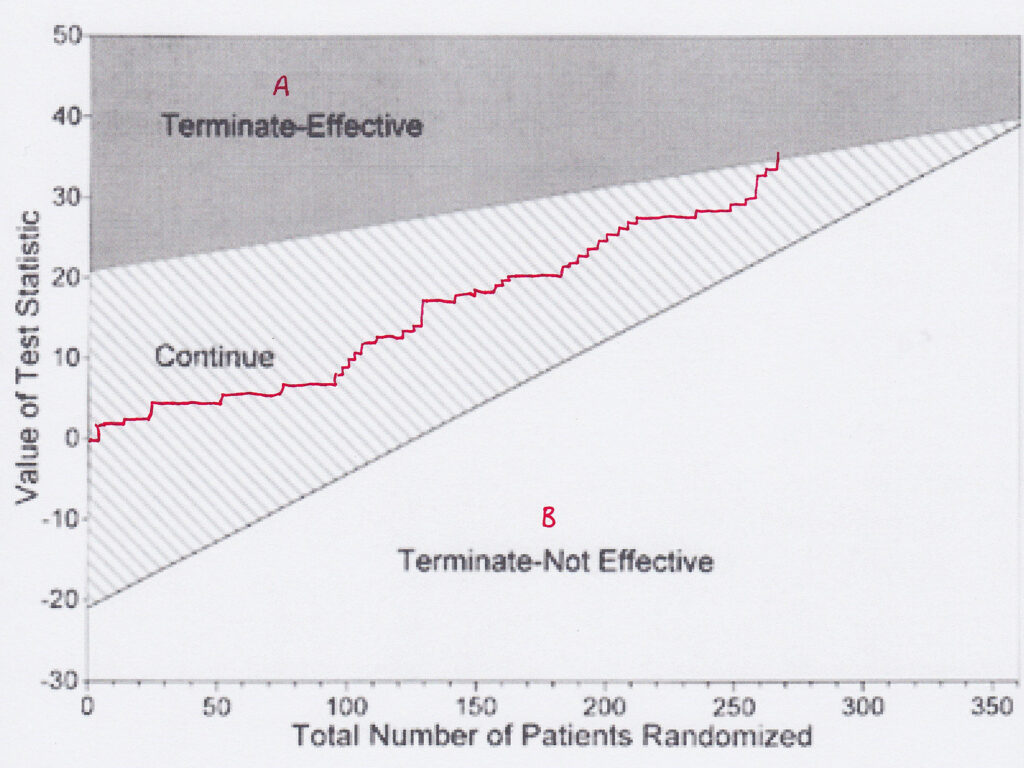

I agree that many new drugs are no better than those they replace. That they do succeed may be down to marketing and disinformation. If I read that a trial has shown that new drug B is ‘at least as good as’ old drug A, I want to know what evidence there is. Often the fault is in a misunderstanding of comparative sequential trials. In these, a plot of each patient is made on a graph depending on whether drug A is better than drug B, or vice-versa. A plot enables one to tell, and you can change the confidence limits, when one is better than the other. However, if the graph line continues and fails to show a difference, it doesn’t mean there is no difference, merely that you have failed to prove that there is a difference. The two are not the same. Many such trials are interpreted, however, as showing no difference.

Yes, huge amounts of money are spent on drugs that are useless, such as Avandia and Tamiflu. There is no excuse for withholding data (hello, I hear statins again). But such developments underpin my argument that successful drugs must finance the failures – and there’s no way of knowing which will be which when you start.

Conflict of interest alert. I have been to conferences that were heavily supported by drug companies, and even been paid to go. Companies were particularly keen to finance British rheumatologists’ trips to the American College of Rheumatology conferences; I never went to one of them. But is it necessarily a Bad Thing? Am I really being bought? Certainly in my specialty there were so many alternatives to choose from that one could only be accused of being bought by the whole lot. Did I go to conferences to learn about new drugs? A bit, but I was mindful of all the trial pitfalls on show, and so carried large quantities of pinches of salt. No, I went to meet my colleagues and learn from their experience, not only of drugs but of management issues, clinical problems and other important but drug-unrelated things, and learn about real and significant scientific breakthroughs. Even in science, things are not black and white; one line of investigation into a viral origin for rheumatoid arthritis occupied several departments for some years, but was eventually found to be false thanks to a contaminated assay. But if the conferences were not supported by the drug industry, many would in all probability not happen, which could be a disaster for medicine. I have no doubt that there are egregious attempts at bribery, but one has to look at the pros as well as the cons.

I once gave a talk to a group of general practitioners about non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. It was in the evening, and a drug rep supplied food. I told them not to use his drug; there were others that were older and thus better-researched. The drug was Vioxx. This was before the scandal of data concealment. My opinion was based on scientific evidence (and lack of it). Had the food been missing I would not have had an audience. So inducements may have their benefits.

I can only agree with Rod that negative evidence is suppressed. It should be a requirement that all registered trials are published, positive, negative or abandoned. And like must be compared with like. Statins again. The benefit of many is suggested to be a 50% reduction in heart attacks. Sounds great, but 50% of what? If the absolute risk of a heart attack is 5%, then a 50% reduction takes it down to 2.5%. Not so great. Meanwhile the side-effects are always given as absolute risks, so benefit is overstated in relation to risk. In addition, attempts to access the source data of some research has been impossible, so one cannot judge the veracity of the conclusions. The excuse given is commercial sensitivity or confidentiality. Not a good enough excuse. This should be something properly investigated. There is accumulating evidence that the (small) effect of statins is not related to their cholesterol-lowering properties, and the whole basis of the cholesterol-heart hypothesis is based on selective data-picking. Malcolm Kendrick and Uffe Ravnskov are two authors who have dissected this in detail. The astronomical cost of statins warrants a closer look. Well, you may think, they are actually cheap pills, but multiplying a low cost by a large number comes out worse than multiplying a large cost by a small one.

I disagree with Rod that nationalisation of the industry is the answer; it would be rapidly bogged down in bureaucracy, and thus unworkable. So let’s stick to something easy. All drug trials should be registered (already coming in the U.K.), all registered drug trials should be published, and all trials should have their source data open to independent review, and all trial authors should append truthful conflict of interest statements. Not only that, but the statistical methods of each trial should be transparent. The possibilities of inappropriate analysis, hiding of unwanted facts and outright fraud and deception would be dramatically reduced by these simple measures. Suck it and see?

Dr. Andrew Bamji is Gillies Archivist to the British Association of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons. A retired consultant in rheumatology and rehabilitation, he was President of the British Society for Rheumatology from 2006-8.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

And for a pretty good history of it.

Just read “The Real Anthony Fauci” by Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

And for living proof of the known bad effects of the jab thus far :-

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S027869152200206X

Just in case you thought that circulatory problems were the only thing to worry about.

The problem (discounting for a moment any evil intent) is that the geneticists behind the mRNA jabs don’t understand much of the little we know of both innate and acquired immunity and have to rely on the computer coders and subsequent algorithms being correct as regards ie “blast”.

All the experts in different areas have to rely on all the others being correct.

And the chances of that in such complex systems?

I would also add to your last paragraph ‘NO drug to be released to the general public without an exhaustive ten year follow up’

Ignoring the obvious elephant in the room, I believe there was also the swine flu vaccine (rolled out after four years, then found to cause narcolepsy) and SSRI anti depressants, which were rolled out long term after only a six month trial, and now known to have horrific withdrawal effects.

As to awareness of ARR and RRR, it took me about two minutes to understand that, and a further two minutes to work out, based on the results I got, that I should give AstraZeneca a miss, but I don’t know how you go about educating the masses on that one.

A little known fact, that I got from my best friend, who was head nurse in a doctors practice at the time….is that even knowing that some of these side effects were becoming clear from The Swine Flu Vaccination, the Government used it for the flu vaccine that year without making it clear what vaccine they were using…this was to use up the vast ‘overstock’ they had left…my friend outright refused to vaccinate people without giving them this important information….the doctor relented and in that one surgery people were informed…but how many weren’t?

Suck it and see? That would indeed seem to be pfisser et al.’s view of their drugs. Do they not have a judicial track record a mile long of concealing bad data? This article to a great extent ignores the whole obscene situation with the current global trial of a highly experimental drug for no reason.

Suck it and see may apply when someone has a very debilitating ailment or a terminal disease – most people would probably be willing to take experimental medication, primarily from the perspective that there isn’t much to lose.

That is not what is happening now. Literally hundreds of millions of healthy people have been injected with chemical garbage so that the pharma companies can rake in money while their victims get to “suck it and see”, even though they never needed this garbage in the first place and both the medical profession and pharma knew this full well. They have now managed to make “suck it and see” the new safety trial, while still lying to people that the garbage they are peddling has been fully tested and found safe. If they literally said “suck it and see” I suspect the uptake would drop significantly. From what I gather mRNA drugs for all sorts of ailments are now being developed based on the lie that this stuff has been tested to the nth degree and found safe (and effective). Repeated pokes of the covid poison are being shoved into people without any trial whatsoever, even with the knowledge that not only does this garbage not do very much for very long, but the side effects that are already visible are beyond the pale.

In relation to the latter point, I suggest that those who have not yet done so have a look at Igor Chudov’s substack and an article he posted yesterday. He quotes a prediction written by someone on another substack back in September 2021. It is almost verbatim what we are witnessing now, quite frightening. If that person could figure this out back in September and we are in fact seeing what he predicted play out, only a moron or a psychopath would still have any faith in pharmaceuticals at this point in time.

Yes..it’s been made even clearer with the FDA giving permission for two jabs for babies, yesterday…even though the evidence for any ‘efficacy’ is negligible…..

utterly shocking…

https://alexberenson.substack.com/p/urgent-omg-the-pfizer-data-for-kids/comments?utm_source=%2Fprofile%2F12729762-alex-berenson&utm_medium=reader2

Igor Chudov also pointed out that if a pregnant woman has her two initial jabs, then a booster, then has the baby, when the baby’s six months old it can have its two jabs…so by that time it’s been exposed to FIVE doses of toxic spike protein!!! Who can possibly tell anyone that that is ‘safe’?

Things are even worse than feared for the babies & future generations. The CDC are going for the youngest age group first.

[Forwarded from UK Medical Freedom Alliance]

https://tobyrogers.substack.com/p/breaking-news-cdc-launches-sneak?s=r

“National Vaccine Advisory Committee. Melinda Wharton gave her update from CDC… and they have scheduled a special two day meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) for TOMORROW (Friday, June 17) and Saturday (June 18). The agenda is here:

https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/agenda-archive/agenda-2022-06-17-18-508.pdf

Friday they will discuss safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy of Moderna in kids 6 months through 5 years of age AND Pfizer in kids 6 months through 4 years of age. Saturday they will vote. The entire process is set up to rubber stamp the VRBPAC meetings from yesterday.

CDC is going to hold off on debating Moderna in kids 6 to 17 years old until next week (they have another meeting scheduled for June 22 and 23). The CDC has decided to target the littlest kids first.”

PLEASE SHARE FAR AND WIDE

This article reads to me like someone defending a serial killer by giving examples of good things he’s done. He held the door for an old lady, he always smiled and said hello to his neighbours, he was good at his job and never missed a day.

No doubt they do some good things. But they ruthlessly push to have their products administered often knowing they don’t necessarily help much, they actively sabotage effective competing products at the expense of human life (so I know they don’t care about people’s lives if they get in the way of their profits) and they are now at the centre of an effort to impose a global biomedical surveillance system that would result in forced or highly coerced administration of their products.

I wouldn’t care so much about them and would be more open to the “nuances” if they weren’t trying to force themselves on me.

A lot of them probably like dogs too

But great anology, it is a defence of serial killers. Quite a few of these ‘mad professors’ probably have the same disdain for human life as any bog standard serial killer, the only difference would appear to be the diploma on the wall.

Yes, I don’t like being violated myself.

My attitude towards chemicals I would be ingesting, or having injected into me is “buyer beware.” I don’t trust the Pharmaceutical companies at all, and following the last 2 years’ disgraceful behaviour by the Government/medical profession, I don’t trust them either.

I’m in my early 60s. The last time I saw a GP 3 yrs ago (apparently essential before the nurse would clear wax from an ear) he asked what medicines I was taking and when I said “none” his response was “we’ll get you eventually.”

And that appears to be the objective – drug pushing. The Pharmaceutical companies push their drugs to the medical profession. The medical profession then push the drugs to vulnerable and poorly-informed patients.

Ignoring data and just changing the finally presented numbers to fit the narrative is rife at all levels, in my experience.

Time and again, I have spent hours producing self-serve reports which are based on the data available, rigorous testing of my backend SQL routines, clear caveats detailing database quality issues, and so on, only to have very senior managers export to excel and edit everything to suit. Which would be fine for them perhaps, if they didn’t then come back to me three weeks later and tell me,

“Your numbers are wrong.”

Little did they know that I could see very well that they had ‘adjusted’ my work.

Certainly if pharma patents were abolished, the way drugs are developed and the funding for their testing would have to change; that in itself is not a strong argument in favour of patents. Germany had a flourishing pharma industry in the 1930s before pharma patents were introduced. Ways would be found to fund development and testing, people and charities would likely crowdfund research. A major problem with patents is that they encourage pharma companies to develop the wrong kind of drug, namely one that is “novel” (i.e. with an unknown safety profile, hence needing a lot of expensive testing) and where cost and efficacy are secondary considerations. Scarce technical resources are misdirected into securing monopolies rather than delivering value to patients. Patents and the money they bring in also mean that undue influence is brought to bear on universities, journals, the media, governments and the entire medical establishment in order to drive out competition, including competition from low-cost repurposed drugs, which universities don’t dare to progress beyond the pre-clinical stage for fear of losing grant money.

Dr Bamji makes a good case but after the last couple of years my view of the pharma industry has been completely undermined. Basically I don’t trust it one bit.

Owing to ticker trouble going back twenty five years I have for most of that time been taking statins. A few years ago I started to notice that after a cardio work out my mood changed and I would feel violently angry shortly after leaving the gym. It became so bad I genuinely feared I might hurt someone.

A look on Dr Google revealed I was not alone. And what did we all have in common?

Statins.

I reported this to more than one GP. The assistance from one doctor was a few pages from the computer on anger management which got FIB.

Since then I have been “encouraged” by various doctors and cardiologists to go back on statins. Hardly surprising that my faith in both is all but non-existent.

An addendum – I am off statins and will never go back on them.

I don’t blame you! Sebastian Rushworth MD published an article on overprescribing of drugs on his substack.

Re statins I wouldn’t worry, you’re only statistically going to die 4.96 days sooner than if you didn’t take them

https://sebastianrushworth.com/2022/06/14/should-the-patient-really-get-the-drug/

Thanks for the good news BB

Dr Maryanne Demasi exposing the statins con and her personal experience of being censored and silenced. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t2dHQSj90-A

(Similar conclusion as BB mentions statins may give 4 days more life potentially for some people who are at higher risk. So majority are taking them for no benefit and risking side effects).

Drug companies could be made to publish risk / benefits for anyone to make a reasoned assessment of whether taking a medicine is better for them or not. Those could be included in places like the British National Formulary (BNF).

Thanks

The main thing to take away from this article is that most of modern medicine is really nothing but an enormous body of witchdoctor lore: Create a random concoction. Give it to people. See what happens. If it’s good, claim the concoction caused it, if not, blame it on something else. Times a 100,000 or so.

Many thanks for providing some balance to Driver’s earlier article.

They’re still bloody crooks and they are only interested in the bottom line.