by Edward Chancellor

The actor Mark Rylance is currently performing in the title role of an interesting new play at the Bristol Old Vic. Based on an original idea of Rylance’s and scripted by Stephen Brown, Dr. Semmelweiss relates the true story of a physician who, while working at the Vienna General Hospital in the mid-19th century, discovered a simple procedure that dramatically reduced the death rate for patients in his care.

Semmelweiss observed that maternity wards overseen by doctors experienced many more deaths than those attended only by midwives. He attributed the difference to the fact that medics went straight from performing autopsies on dead women to delivering babies, whereas midwives were kept out of the dissecting chamber. Semmelweiss concluded that the doctors must be infecting their patients with what he called “cadaveric particles”, and recommended that they wash their hands in chlorinated water before entering the wards. After this recommendation was put into practice, the death rate from childbed fever (puerperal sepsis) collapsed.

Despite Semmelweiss’ brilliant discovery, the Viennese medical establishment refused to accept his ideas and the wretched doctor, driven mad by his failure to prevent unnecessary deaths, ends up in a lunatic asylum. His failure owes something to his personality: in the play he is portrayed as excitable, self-absorbed, intolerant, sanctimonious and, at times, cruel in his obsessive desire to get his ideas accepted. As a result, he alienates both sympathetic colleagues and a lady grandee from Court who wanted to help. Visionaries are often difficult characters.

But the greatest obstacle turned out to be Semmelweiss’ superior, Dr. Johann Klein. Klein had his own pet theory as to the cause of childbirth deaths: he believed that the sickness was airbone and advocated more fresh air in the wards. Besides, Klein feared that Semmelweiss’ notions contradicted the findings of a recent Imperial Commission and he didn’t want to offend the hospital’s benefactors. Even though Semmelweiss’ experiments proved he was wrong, Klein refused to heed the evidence.

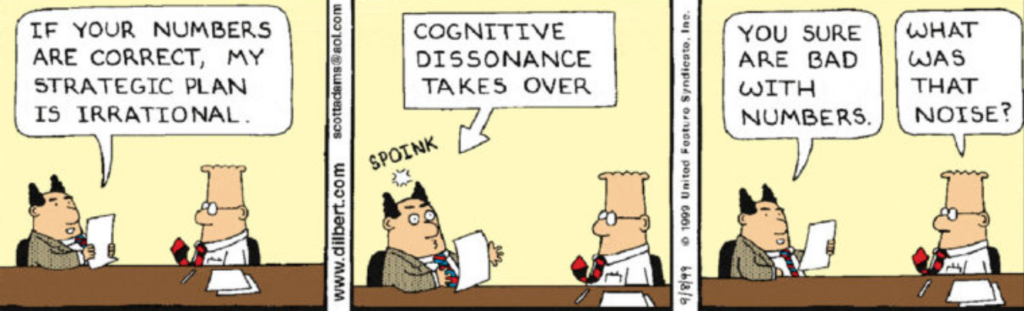

The case of Ignaz Semmelweiss is cited by Carol Tavris and Elliott Aronson in their masterful study of cognitive dissonance, Mistakes Were Made (but not by me). Cognitive dissonance arises when people are confronted with information that contradicts their firmly held beliefs. Instead of changing their minds, most people behave like Dr. Klein and ignore contradictory or dissonant information. For them, ‘believing is seeing’ rather than the other way around. This is particularly the case when new evidence reveals that an individual or group has made an extremely costly mistake. Cognitive dissonance explains why neither George W. Bush nor Tony Blair has ever publicly accepted that, as most impartial observers now believe, the 2003 invasion of Iraq was an unmitigated disaster.

Semmelweiss’ colleagues were unable to accept his findings because that would have required acknowledging that they had played an unwitting role in the death of hundreds of women. Tavris and Aronson write:

This was an intolerable realisation, for it went straight to the heart of the physicians’ view of themselves as medical experts and wise healers; and so, in essence, they told Semmelweiss to get lost and take his ideas with him. Because their stubborn refusal to accept Semmelweiss’s evidence – the lower death rate among his own patients – happened long before the era of malpractice suits, we can say with assurance that they were acting out of a need to protect their egos, not their income. Medicine has advanced since their day, but the need for self-justification hasn’t budged.

According to Tavris and Aronson, doctors are notoriously reluctant to admit mistakes because they fear losing their aura of infallibility and omniscience, which they maintain is essential to patients’ confidence and compliance. The medical profession is not alone at fault. Having identified a crime suspect, detectives search for, and at times fabricate, evidence to support their conclusions (while ignoring that which doesn’t). Jurors who make up their minds early in a trial are more likely to support extreme verdicts. Having secured a guilty verdict, prosecutors are loathe to reopen a case even in the face of incontrovertible DNA evidence.

Self-justification may help us sleep at night, write Tavris and Aronson, but “it permits the guilty to avoid taking responsibility for their deeds. And it keeps many professionals from changing outdated attitudes and procedures that can be harmful to the public.”

Which brings us to the pandemic. For two years, the world has experienced a succession of lockdowns and other ‘non-pharmaceutical interventions’ to arrest the spread of SARS-CoV-2. A recent study from Johns Hopkins University suggests that lockdowns saved few if any lives. There’s scant evidence that mask mandates slowed the spread of Covid. But don’t expect the public health officials who instigated these policies, politicians who implemented them or commentators who cheered them on, to recant any time soon.

Like Bush and Blair in regard to the Iraq War or the Austrian health authorities in Semmelweiss’ day, they’ve collectively committed too much – their own reputations and the wellbeing of whole nations – to admit error. As Tavris and Aronson put it: “Most human beings and most institutions are going to do everything in their power to reduce dissonance in ways that are favourable to them, that allow them to justify their mistakes and maintain business as usual.” So the official narrative will remain that lockdowns and other measures succeeded.

Yet all is not lost. For a start, the public appears to be increasingly sceptical. Besides, the scientific method requires that scientists change their beliefs once they’ve been discredited. And while individual scientists are not self-correcting, science eventually is. As Max Planck said, a new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it. After his death, even the half-mad Semmelweiss was vindicated.

Edward Chancellor is a financial journalist and the author of Devil Take the Hindmost: A History of Financial Speculation (1998)

Donate

We depend on your donations to keep this site going. Please give what you can.

Donate TodayComment on this Article

You’ll need to set up an account to comment if you don’t already have one. We ask for a minimum donation of £5 if you'd like to make a comment or post in our Forums.

Sign UpNews Round-Up

Next PostWhy the ‘Healthy Vaccinee Effect’ is a Myth and Cannot Explain the Spikes in Deaths at the Time of the Vaccine Rollout