At this two-year point in the pandemic, I’ve been revisiting what happened at the start to get a clearer idea of how things unfolded and whether what happened then can tell us anything useful about the virus. Here’s what we know.

In the last week of December 2019, a doctor in Wuhan noticed unusual pneumonia in six patients who all tested positive for a new coronavirus. We can surmise that to have hospitalised six unconnected people (not all linked to the Huanan market), the new virus must have been circulating in Wuhan for some weeks. Internal reporting of this cluster led to the first public message of a suspected pneumonia outbreak, with precautions advised, from the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission on December 31st. At this point there were just 27 identified cases in hospital, seven of them serious – which wouldn’t seem out of the ordinary for winter.

Despite this inauspicious start, Hubei province went on (according to official data) to have a deadly outbreak, though one that was notably slower burning and milder than later Covid outbreaks elsewhere. It totalled around 4,500 deaths out of a population of 57 million people, making it around a tenth as deadly as the first wave in the U.K., and peaked at 143 reported daily deaths on February 19th (suggesting the infection peak was late January). This doesn’t seem a particularly high death toll for a winter respiratory virus.

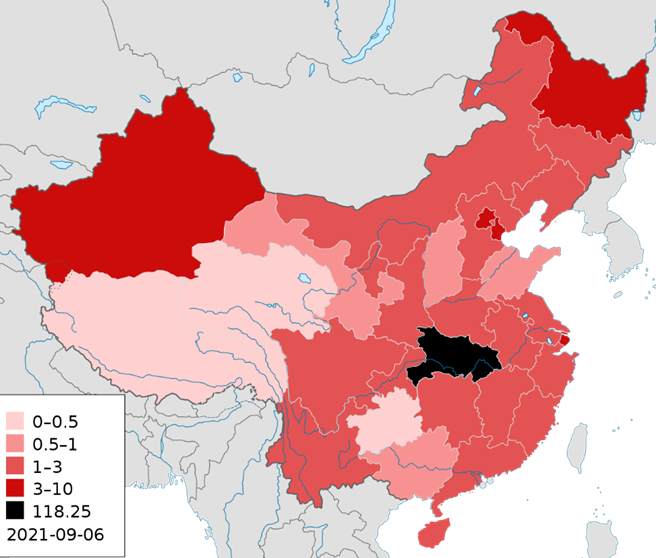

Notably, this initial deadly outbreak was very localised. Hubei was locked down on January 23rd, but prior to that the virus circulated freely for weeks, while millions of people left the province ahead of the lockdown. Despite this, no other province in China suffered a deadly outbreak (see below). While we might be inclined to question China’s official data, it fits with what happened in neighbouring countries – no other country in the region suffered a deadly outbreak of the new virus. South Korea’s outbreak peaked at six reported daily deaths on March 30th, Japan’s (which was the worst in the region) at 24 on May 1st.

The lack of deadly outbreak outside Hubei explains why most people were largely ignoring the rumours of another virus in the East at that time. It appeared to be fizzling out, having done little anywhere outside Wuhan, and the WHO refrained from declaring a pandemic. In all likelihood we would have just carried on ignoring it, as we did the earlier bird flu and swine flu scares, were it not for what happened next.

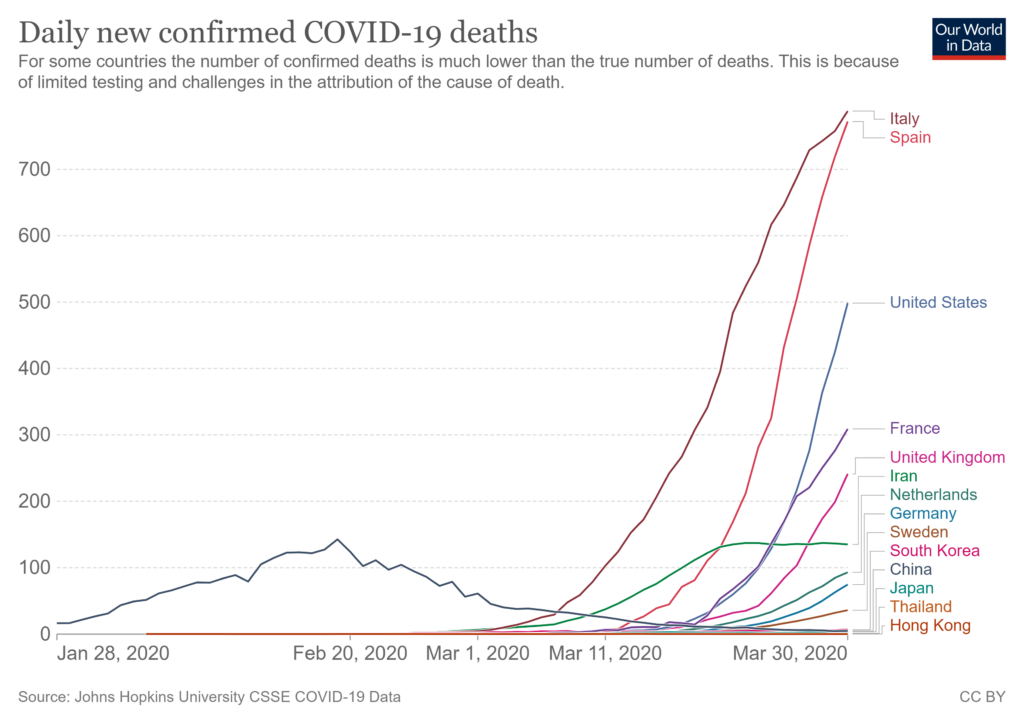

An outbreak in Lombardy in northern Italy led the local government there to order a lockdown – the first after Hubei – in 10 towns covering around 50,000 people on February 21st 2020, seemingly a panic measure in response to the first death in the region. However, that seems to have been an aberration and there was no wider push for restrictions at that point. That came two weeks later, on March 8th, when the Italian Government locked down the northern part of the country. Two days later, it locked the whole country down. The trigger for this appears to have been the extraordinary jump in the death toll. On March 7th Italy reported 36 deaths. On March 8th it reported 133, and on March 10th it reported 168, with full ICUs portending many more to come. The daily toll quickly climbed to a peak of 919 just over two weeks later on March 27th. The WHO declared a pandemic on March 11th, the day after Italy locked down.

It quickly became clear in the first two weeks of March that the outbreaks in Europe were orders of magnitude more deadly than anything seen in the East (see above). A week after Italy, Spain’s death toll climbed at a similarly alarming rate, and other countries soon followed. Italy reached one death per million on March 9th, Spain on March 16th, New York on March 20th, France and Netherlands on March 21st, Sweden on March 23rd and U.K. on March 25th, and all kept climbing to levels far beyond what had been seen in Hubei let alone elsewhere in South East Asia. In this panicked context, the go-to response became lockdown.

Working back from the pattern of deaths, it appears that these deadly outbreaks began in each country at some point in February, many within days of each other, and grew fast. These outbreaks are plausibly linked to one another, and notably follow a similar pattern to the later outbreaks associated with the emergence of variants such as Alpha, Delta and Omicron, where an initial outbreak in one country (in this case Italy) is soon followed by similar outbreaks in other countries as the new variant quickly spreads internationally. This suggests the initial deadly wave in Europe and the U.S. may have been caused by the emergence in northern Italy of a deadlier variant than had been seen in the East. Supporting this, while these outbreaks emerged within days of each other during February and followed a similar pattern of severity, they occurred months after the Hubei outbreak, which (projecting back from the death curve) began some time in November or October 2019, and was a much longer, slower burn. One explanation is the Hubei outbreak was caused by a less transmissible, less deadly variant. If so, it’s unclear why this ‘Hubei variant’ didn’t have the same effect elsewhere in South East Asia or the world – why was the deadly outbreak entirely localised to Hubei? Nonetheless, there is evidence that some form of SARS-CoV-2 was present globally throughout the winter of 2019-20 – though with that winter being in many countries the least deadly in history, this variant or variants was evidently either very mild or not very transmissible or both.

Since the emergence of the (hypothesised) nastier variant of SARS-CoV-2 in Italy in February 2020, similarly virulent variants have emerged such as Alpha and Delta, while Omicron may be a return to an earlier milder form. If so, was it just bad luck that, just as SARS-CoV-2 seemed to be fizzling out in February 2020, a nastier variant emerged in Italy that terrorised the world and shunted us into copying China’s overreaction in Hubei? Or was there something about SARS-CoV-2 that made this occurrence inevitable, or at least odds-on? Does the furin cleavage site that makes it so transmissible make it more likely it would hang around long enough to mutate into the more dangerous forms we have seen?

Mentioning the furin cleavage site brings up the suspicion that the virus originated in a lab, presumably as a leak. A furin cleavage site is not found in viruses of this sort in the wild but is a common change made to them in a lab. If it did leak from the Wuhan Institute of Virology, presumably the leaked virus is the one responsible for the localised deadly outbreak in Hubei (otherwise the connection between the outbreak and the leak would be coincidental). Was it then milder variants of the leaked virus that went round the world that winter, rather than the deadlier one in Hubei? If not, why did only Hubei have a deadly outbreak in December 2019-January 2020, even though the virus appears already to have been present around the world by December?

Seeing the emergence of the pandemic in late 2019 and early 2020 as, in part, a variant story, helps to fill in some gaps, such as the odd delay between the Hubei outbreak in November-January and those in Europe in February-March, as well as the massive difference in severity. The pieces don’t fit together entirely neatly though, and questions – especially about why the Hubei outbreak was so localised and uniquely deadly in South East Asia, why there is evidence of a milder form of SARS-CoV-2 around the world in winter 2019-20, and the role of a laboratory – remain.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

It is reported elsewhere that more people have died in the four / six months of taking these “vaccines” than in the last twenty years of vaccines.

What will be the true death count of taking these covid “vaccines” be in the fullness of time ? No thanks Matt Mengele – stick yr needle where the sun don`t shine !

That’s certainly true for the USA. Not sure about the UK but given that we don’t tend to vaccinate as much as the US it’s likely to be the case here.

Numbers are very sketchy. Their is wide disparity in deaths or serious adverse events per dose administered across Europe. The reporting is all over the place.

… which is typical of so much in this confected shit-show. Indirect confirmation of the way in which accurate data is the enemy of the official narrative.

In practice GPs act as gatekeepers to the Yellow Card system, a patient will consult with them and the GP may persuade them that it’s an unrelated condition; the latest Delingpod podcast is interesting on this.

Not true. If you think that you’ve had an adverse reaction to any drug then you can submit a yellow card via the MHRA website at https://yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk/. You do not need to inform your GP.

You can in principle, but if it’s more than a mild reaction, you will generally first have it checked out by your GP, who will tell you it’s not the vaccine. Rightly or wrongly, people tend to believe their GPs.

And you believe you’ll get to see a GP? You’re having a laugh

You can’t even get through on the phone to our GPs who are being paid in full and having their pensions topped up – to do nothing. We no longer have a GP service fit for purpose – let alone free at the point of delivery. We have all paid through the nose for this rubbish service.

I’ve just reported my Dad’s reaction regardless. Don’t care.

What do you do if you’re dead?

I suppose you get added to the dead with covid statistics.

So if the UK doesn’t vaccinate as much as the U.S., and we’re vaccinating the majority of the population with CV19 vaccines, and assuming that the death rate is the same as the U.S., doesn’t that mean the difference will be even more stark?

From one chart I’ve seen, the average number of deaths from vaccines is around 100-120 per year, sometimes lower. And so far it’s been over 2000 deaths associated with CV19 vaccines.

The data is incomplete, so it’s impossible to make a true judgment at the moment.

The last I heard for the UK – there were 1100 deaths post vaccine (but of course these victims died of their serious underlying health conditions – while Covid victims (with serious underlying health conditions ) died of Covid)

Odd that

Over 7,000 deaths in the Eu post vaccination so far. . The UK will have plenty as well, just keeping it under wraps. Why? Yellow card data

Can you give a reference?

If you just mean self-reporting systems such as VAERS or the UK Yellow Card system they have no relevance whatsoever. If you vaccinate millions of people then tens of thousands who have been vaccinated will die in the next two to three months because they would have died anyway. It is not surprising that a small percentage of those self-report as an adverse incident given the intense media focus.

MTF why is it that every time I read one of your posts, I’m struck by how dishonest you are and how you seem to always be spreading misinformation and blatant lies? This is another one of those occasions.

Just so we are all clear, there is consensus that systems like VAERS and the YellowCard system suffer from under reporting, not over reporting. It is difficult to pinpoint by how much. but estimates that only between 1% and 10% of actual events are reported are common.

To prove this, here is just one article from the British Medical Journal from 2011, before they started publishing lies and serving nefarious governmental agendas.

Rapid Response: Underreporting Vaccine Adverse Events

https://www.bmj.com/rapid-response/2011/11/02/underreporting-vaccine-adverse-events

How can public health officials rely on a system that reports fewer than 1% of adverse effects?

With the criminal, experimental rollout of untested, approved for Emergency Use Only “vaccines”, for which the animal trials were skipped, despite the known, inherent issue of pathogenic priming and ADE with Coronavirus vaccines, which criminal, deceptive forces within the government have conspired to force onto the unsuspecting, duped Britsh public (4 players are being prosecuted in a private criminal prosecution with more to come including charges against criminals in the media), despite the fact that there are safe and effective drug and alternative treatments available for serious cases of Covid19, like Ivermectin, HCQ, Vitamin C, Vitamin D, Zinc and more, every rule of medical etchis and protocal has been broken and the level of adverse events seen so far is unprecedented, and not in a good way.

COVID Vaccines: Necessity, Efficacy and Safety

Doctors for Covid Ethics

https://off-guardian.org/2021/05/05/covid-vaccines-necessity-efficacy-and-safety/

In short, the available evidence and science indicate that COVID-19 vaccines are unnecessary, ineffective and unsafe.

It also cannot be repeated enough that the whole basis of the scam, that there is an Emergency which requires intervention, is a complete and utter lie and a fraud. Covid19 has an IFR of 0.15%, in other words its mortality rate is exactly like a normal seasonal flu. We have a situation where influenza went missing and Covid19 took its place, so the overall risk of just being alive did not change at all, you are at no more risk of respiratory disease now than you were 24 months ago. The major risks are introduced as a result of taking the vaccine, in which case many have taken massive unquantifiable risks with their health which could materialise ,much further down the line. All for no good reason other than they have been tricked.

Global perspective of COVID‐19 epidemiology for a full‐cycle pandemic

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/eci.13423

Global infection fatality rate is 0.15‐0.20% (0.03‐0.04% in those <70 years)

So UK Column have put together a useful app which users can use to analyse the adverse events which have been reported to the YellowCard system. The Covid19 vaccine rollout has been responsible for paralysing people. blindness, heart attacks, blood disorders, immune system disorders, death and more. Much more. To date, there are 786,350 adverse events registered and 1,135 deaths.

As I previously showed, despite the dishonest and misleading statement of MTF, all the evidence suggests that there is a massive under-reporting of adverse events and deaths to such systems. We have all seen the stories about whole Nursing Homes being vaccinated, only for a wave of “Covid” to sweep through soon after leaving dozens dead, so the extent of the under-reporting is an unknown but likely quite high.

Given what we know about under reporting, you could put a zero on the end of the figures quoted and that would be nearer to the truth than the actual figures quoted, due to the inherent flaws in the system and the clear desire from the most dishonest government in history to conceal vaccine harms.

COVID-19 Vaccine Analysis

https://yellowcard.ukcolumn.org/yellow-card-reports

Please see my reply to RickH below.

Hi TheFascistCoronaFraud,

I think he’s either paid by the government or he’s a retired IT help-desk operative with too much time on his hands. Either way, he can read and read statistics but he’s not very good at analysing and assimilating the data to come to any meaningful unbiased insight.

He has admitted to me that he has no relevant professional experience or medical education connected to what he comments on.

Winston (I assume that is your name?)

I didn’t want to bring personal details into this debate. What matters is the evidence presented and the validity of the arguments – but since you persist in conjecturing about my background – here is short CV. Some of it you know already but others may not.

I am a retired IT consultant and instructor (I have never worked on a help desk in my life but I have taught help desk staff). As well as my BA (many years ago) I have three masters degrees and am studying for a fourth as a hobby. The masters degrees were in Operational Research (with a heavy dose of statistics), Science and Society, and Web Science (with a heavy dose of extracting and using data from the Web). I also have a Diploma in Statistics including a module on medical statistics. Since retirement I have had three papers published in peer reviewed journals on data related subjects and done several data related projects for the public sector. The reason I have time on my hands is because I was diagnosed with myeloma (an incurable but treatable blood cancer) last March and am now recovering from my second stem cell transplant which means I can’t get out much. I participate in this forum because I consider the vaccination programme to be vital but also because I want to understand the arguments for doubting it.

All of which is totally irrelevant to the validity or otherwise of any argument I might present. Let’s move on from personal matters.

“I consider the vaccination programme to be vital”

Why?

It’s certainly vital to the globalist agenda, but why is it vital to you?

It is vital because:

1) The world needs to get some degree of immunity among a large proportion of the population. Until then, we will have a series of outbreaks and lockdowns (whether you think they are good idea or not, that is the way most governments will react). There are two ways of getting that immunity – catching Covid or vaccination. Vaccination is quicker and safer.

2) Once this has settled down it seems likely we will be in a situation like flu which is greatly helped by periodic vaccination drives. So we will need vaccines.

I know you will disagree with some of this.

I see that my CV got 18 thumbs downs! On reflection I think that is fair enough. Who cares about me – what matters is the evidence and the arguments. I also regret disclosing so much personal information. So I have asked the administrator to remove the comment. I don’t know if replies are automatically removed at the same time.

Brilliant response.

Bearing in mind these figures are only for the UK. Why anyone would want to take this experiemntal treatment is beyond my comprehension.

I am obviously an idiot for refusing to have this?

well here’s an other club member, I have read the various companies track records and boggle at them getting immunity from prosecution

Actually, the sample contained in official reporting systems is known to have the reverse effect.

It minimises the true rate of side effects.

It doesn’t matter if it minimises it or not! It makes no sense to consider the deaths following vaccination unless you compare it to the deaths you would expect from the same number of people of the same age profile if they had not been vaccinated (This is exactly the argument that sceptics use to criticise Covid death figures).

I have made this point before but somehow it didn’t sink in.

Let’s take the UK figures (the US is very similar). To date 36.5 million people have had at least one dose. The UK mortality rate is about 0.95%. Those 36.5 million are mostly older so their chance of dying in a year is at least 0.95%. So if they had never been vaccinated we would expect about 347,000 in this group to die every year i.e. about 29,000 a month. Let’s estimate the average time since vaccination at two months (it makes little difference if its one or three). Then we would expect 58,000 out of those who have been vaccinated to have died for other reasons following their vaccination. There have been just over a 1000 reports of fatalities on the yellow card system. It seems likely, given the fuss that has been made about it, that anyone who was even slightly wary of the vaccines and was close to someone who died (for whatever reason) following vaccination would report it as an adverse event. It is quite surprising that only a 1000 of those 58,000 deaths have been reported.

TheFascistCoronaFraud seems to think I am dishonest and tell blatant lies. If someone cares to point out anything that I have written above that is false I will address it.

Yes, you’re absolutely right.

And this is why many disease specialists were saying last year that the pharmacovigilance for the covid vaccines should be to record every single hospitalisation and death for a period post vaccine (28 days seems popular) so that the impact of vaccination could be compared against the background rate.

To the surprise of many they didn’t do this, but instead relied upon the rather poor yellow-card system.

As a result we really don’t know what the complication rate of the vaccines is. We can make inferences from the yellow card system, but only that.

It is rather extraordinary that we didn’t do much more robust pharmacovigilance.

By the way, I now know of 3 people that that were healthy but suddenly died within 28 days post vaccination (50’s 2x heart attack 1x stroke). Sure, it might well not be related to the vaccine, but none of them were entered into the yellow card system as a possible vaccine related death, and so your ‘it seems rather likely that [death following] vaccination would be [reported as] an adverse event’ seems unlikely to me.

“And this is why many disease specialists were saying last year that the pharmacovigilance for the covid vaccines should be to record every single hospitalisation and death for a period post vaccine”

I guess this might be a good idea. It would reassure people. But it is not the only way of investigating deaths following vaccination.

Doctors have to indicate if they believe that vaccination might be part of the cause on the death certificate and the ONS does track this.

If there are a statistically significant number of extra deaths following vaccination it should show up as a rise in deaths as more of the population is vaccinated – particularly in situations where the virus is at a very low level and people are still being vaccinated e.g. here and Israel.

And of course the MHRA look at all adverse reports and investigate any that concern them. I have no idea what proportion of reported deaths are investigated or how.

“If there are a statistically significant number of extra deaths following vaccination …”

There are in many countries, and the data for this country shows that following the vaccinations, the decline of mortality was slower than after April 2020, as I’ve previously pointed out.

“unless you compare it to the deaths you would expect from the same number of people of the same age profile if they had not been vaccinated”

Yes, and this is exactly what we’re not being told. You can be sure if it was favourable to the vaccines, information on all-cause mortality against a control group would have been published. Instead we get studies that start two weeks after vaccination.

… and on top of this, we know that government pushes complete lies in their pursuit of the vaccine assault. As I’ve quoted :

“COVID-19 is the biggest threat this country has faced in peacetime history, which is why the UK government is working to a scientifically led, step-by-step action plan for tackling the pandemic – taking the right measures at the right time.”

… the opening paragraph of the essential document paving the way for rushed vaccines.

Nothing could betray the suspect motivations more clearly.

But but but…. You could use a similar argument about “corona” deaths, a bad cold tends to take out those within a few months of their sell by date, so unless there was a significant increase in total deaths by the end of the year, the virus is not bad enough to worry about?

Absolutely and such an argument would be valid. We had about 80,000 excess deaths last year (more than 5 year average). This year remains to be seen.

There is no such thing as ‘excess deaths’ in any meaningful sense. It’s a nonsensical term.

What there are is deaths above a sensible baseline.

5 years is a totally inadequate baseline to provide a historical comparison.

Due to withdrawal of medical care? And when did the excess start clocking up? And were the last 5 years normal or exceptionally low?

The last five years had plateaued, after falling for decades. 2020 was higher than the last five years, but not as high as 2008.

… and if you look at two-year periods rather than single tears (thus accounting for balancing factors), one sees a return to the 25-year mean, not a major upturn.

It was the highest population adjusted death toll since 2008.

yes – or to put it another way we lost 12 years progress in reducing death tolls.

Uh? What a skewed interpretation!

You mean that an abnormally low sequence of mortality came to an end by natural causes and a continuing upturn from an abnormally low level.

That’s equilibrium.

It’s all right, child. No need to panic – it’s not that serious.

(And curtailing normal life does not equate to saving it)

I’m convinced you’re not lying.

You’re just not very bright.

The reporting systems have remained the same, with the same potential flaws for years. But the data is as good as it gets.

The simple fact is that the reported incidents, compared within the same framework indicate massive concerns for these experimental ‘vaccines’ when compared with previous medications.

The CDC suggests that reported incidents for the last five months are equal to the previous 21 years!

Well our relationship has developed a bit from your previous comment which accused me of blatant lies! At this rate we will soon be best of buddies.

If reported incidents are very much higher than other vaccines then that is something to be explained. It is a big logical jump from there to concluding the vaccines are causing more incidents than other vaccines. The sheer hype and debate (like this one) make this vaccine roll out quite unlike any other. It has a media profile many, many times higher than any other.

“your previous comment which accused me of blatant lies!”

Do please cite.

I apologise. It was TheFascistCoronaFraud not you. I get a bit confused by the stream of abuse and obscenities that I receive on this site.

It is true that no one single death can necessarily be attributed to a vaccine or to natural causes, but the reporting systems exist as early warning systems for new drugs. The warnings for the CV19 are flashing a bright red right now, and the vaccines should be properly evaluated before continuing to be given to people.

It’s put a friend of mine in hospital with blood clots, and she was lucky not to have been killed by them. It’s not mere coincidence that it’s happened. How many coincidences do there have to be before someone says there’s a pattern, and the vaccines are responsible?

What makes you think the vaccines are not being evaluated properly? We have vast numbers of vaccinations to analyse (whole nations). Many organisations similar to the MHRA are studying them intensely given the media circus round them. So much so that they have picked up the incredibly small chance of a CVT.

I am sorry about your friend. I had a DVT about ten years ago and it is not pleasant. But how do you know it is not a coincidence? They are surprisingly common. You have roughly one a thousand chance of a blood clot every year. Was she by any chance on the pill? That would raise her chances considerably.

“What makes you think the vaccines are not being evaluated properly?”

By definition – they aren’t. This is a process that requires proper, staged and blinded RCTs – preferably in the hands of an independent monitor.

The current ‘real world’ selective data is a dog’s dinner of fitting data to the narrative.

Litmus test of good reporting : Is the ARR quoted, or just the relative figures,. This is always the marker of concealment.

What we are seeing is a PR campaign by interested parties, not scientific rigour.

Would you take assurance from a snake oil salesman who is proven to lie?

More people have died from taking vaccines in the last 4 months in the USA than taking vaccines in the last 15 1/2 years.

what planet are you from? no relevance whatsoever? huh? A pdf report that shows over 750,000 adverse health events irrelevant? To me that shows how utterly brainwashed you are, or are you 77th brigade perhaps? A tiny little voice paid to keep up the Gov bullsh*t when deep down I suspect you’re frightened at what your own Gov are perpetrating upon you. Wake up you shill.

Please see my reply to RickH above.

The spike in deaths that has been observed in the first two weeks after vaccination in many studies suggests that these adverse effects are not imaginary. In particular, the same pattern appears clearly in COVID death counts in countries that prior to vaccination had far lower death rates: Seychelles, many other countries in South/East Asia. Any low-cost prophylactic that showed that kind of pattern would have been banned immediately.

I don’t think it is a spike in deaths. I think it is a spike in cases. (Happy to be corrected if you can provide a reference). The spike in cases is the result of two (possibly three) things. In most countries you cannot be vaccinated if you have had Covid symptoms in the two weeks or so before. So there is a lowering of cases before the vaccination. Then none of the vaccines are effective in the first two weeks which would mean that cases return to normal for a short period before the vaccine kicks in and permanently lowers the rate of cases. Thus giving the illusion of a spike. (This may be exacerbated by people who have been vaccinated not realising they have no immunity for two weeks and taking unjustified risks)

“I don’t think it is a spike in deaths. I think it is a spike in cases.”

Wrong. I’ve looked at the only reasonably reliable data – all-cause mortality.

It’s a spike in deaths

Asia: https://ibb.co/BtFhvk6

Thailand: https://ibb.co/BN1jcB7

Mongolia: https://ibb.co/N2wn2X7

Seychelles deaths took off from zero when the vaccination campaign started https://dailysceptic.org/2021/05/05/why-is-the-worlds-most-vaccinated-nation-locking-down-again/ – that article does discuss “cases” but the deaths also started (from zero) when the vaccination campaign started https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/seychelles/

It’s a spike in deaths. Reference is Worldometers or any other site that records COVID deaths over time; you can see it for example for Seychelles, their campaign began in January and so did their COVID deaths.

The Seychelles had four deaths in the whole of January. I don’t think you can deduce anything from such low numbers. Give me a few more examples.

Their vaccination campaign only started in Janary, it is still continuing and their COVID death rate has soared. A similar effect can be seen in many Asian countries, https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/philippines/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/COVID-19_vaccination_in_the_Philippines#Progress_to_date The reason for choosing Asian countries is that until the vaccine campaigns began, their COVID fatality rate was very low, so the effect is easier to see.

Thank you for all the examples. I am afraid I simply don’t have time to go over each one. Let’s take the Philippines as an example. Their vaccination programme is very small (less than 3% of the population) and started in early March increasing at a steady rate. Their Covid deaths have been increasing steadily since April last year with a slight acceleration in April this year. I have no idea of their overall mortality. Do you?

Do you seriously take this as evidence that the vaccination programme caused the deaths? If so, I suggest we draw this conversation to a halt as we have fundamentally different ideas as what counts as evidence.

How about meeting in the middle, and you provide evidence that people are dying because of Covid-19.

It is a different subject but the evidence seems overwhelming. Doctors in hospitals are signing death certificates to say people are dying of Covid. Do you think they are incompetent?

Based on opinion for which they’re paid extra for. Can you point us towards coroner reports to support your claims these people died of Covid-19?

This is the only subject that matters. Everything else falls apart unless you’re able to prove that Covid-19 is killing people.

What do you mean “paid extra for”. They are doctors working in hospital. They just get a doctor’s salary.

You don’t typically have a coroner’s report if a doctor has signed the death certificate and specified the cause(s).

Guidance produced by the Royal College of Pathologists in February [2020] stated: ‘In general, if a death is believed to be due to confirmed Covid-19 infection, there is unlikely to be any need for a post-mortem examination to be conducted and the Medical Certificate of Cause of Death should be issued.’

They doubled the number of days that a coroner would automatically investigate a death from 14 to 28 days if a doctor had not seen the newly deceased.

This article covers the change of guidance and it’s impact: https://inews.co.uk/news/broken-coroner-service-families-coronavirus-justice-641651

This was all happening while government advisers were still assuring the public that the virus was mostly harmless. They even believed it would only take 3 weeks to deal with it.

And regarding my own faith in doctors? Last year I was misdiagnosed on 2 separate visits to a UK ‘super-hospital’ by two different doctors when I was struck down by shingles. They both gave me fungal infection cream which exacerbated the rash. When I eventually got the correct diagnosis by my local GP, the damage done to my nerve endings was permanent and the scarring is too.

Without autopsy, I believe a huge number of deaths reported as C-19 will be incorrect.

I am sorry about your misdiagnosis. I have had shingles and it gave me three horrible nights.

I have been heavily involved with doctors for myself and others for a couple of years now and have always found them to be extremely competent. You may have been unlucky or maybe the symptoms became clearer as time went on?

I don’t see anything sinister in the guidance on post-mortems that you quote. Although it is in a guidance document, that particular sentence is not guidance. Pathologists don’t decide whether to do post-mortems. They just do it if requested. The sentence is simply telling pathologists that they are unlikely to get a lot of requests for post-mortems for people who have died of Covid.

The majority of Covid deaths are in hospital (see ONS stats) and no one is going to leave a corpse in a hospital for days without a doctor seeing it. So the business of a doctor not seeing a newly deceased only arises in a minority of cases.

I am sure it can be very upsetting for people close to the deceased if the case is to be referred to a coroner and the judgement is delayed. Luckily, as discussed, this is only going to arise in a minority of cases.

You write: “Without autopsy, I believe a huge number of deaths reported as C-19 will be incorrect.” Why? The diagnosis will presumably be based on symptoms plus one or more PCR tests. There are some sensible concerns about C-19 testing as a screening tool but PCR is recognised as effective for diagnosis – even by hardened sceptics. I don’t see what the autopsy is going to add – you take a specimen and subject it to another PCR test?

3% of the Philippine population is over 3 million people. That is a very big sample size and more than enough to draw some robust conclusions.

You write a lot of sh*t, none of it in good faith. You just arguing for the sake of it.

And not only do you not mind the abuse, you crave it.

The bottom line is, are you likely to survive the vaccine? Very. BUT you are also very likely to survive covid? Yes. Which are you more likely to survive? Nobody really knows but it is looking a lot like younger people have better odds with covid than the vaccine. Will you see an open discussion about this in the media? Not a chance.

Now knock yourself out arguing cr*p.

Re Thailand – we had very few covid deaths until the mass vaccination programme started. Same as happened in India.

I have no idea what the correlation between the ‘vaccine’ and deaths is but it seems very odd that this increase happens.

There’s been a spike in deaths following

vaccination. It’s in the data.

It happened in Gibraltar, Seychelles, UK care homes.

Can we add Thailand and India to that list?

Other low-cost treatments for CV19 had been banned as being potentially dangerous, despite being in use for decades, and having an excellent safety record. What does that tell us??

Follow the money trail

I would like to know if the spike in deaths in the old after jabs, usually attributed to Covid, has testing for Covid, or whether in nursing homes they’re seeing Covid symptoms and putting Covid on the death cert, as we know has happened in the past.

Dolores Cahill, She Who Must Not be Named, has said that in the very old the immune response to these very tough jabs in itself could kill, basically from exhaustion at the point with the old and fragile when a cold can kill. And of course a lot of Covid symptoms, like a high temperature, are in fact immune response symptoms.

It sounds very possible to me.

A vaccine is just as much an insult to the system as a disease, if you are malnourished, and can kill.

As described by Kalokerinos.

Most old folk are likely to be scorbutic, so one could expect adverse consequences following vaccination.

Thank you. A new word for me. Scorbutic. Afflicted by scurvy.

Really?

Most old people?

A lot of old people end up with restricted food intake, calorie needs are low , they have no teeth or poorly fitting ones, they eat soft pap not fortified with vitamins. Humans are one of the few species who do not make their own vit C, we lost the gene. We should be consuming several grams of vit C per day, instead the daily recommended dose is tiny, 80 milligrams, just enough to stave off the worse symptoms of scurvy. You need much more when sick.

Same for covid itself I imagine.

They’re dying within days or hours of the vaccine, not months.

Most of the adverse reactions are not being recorded because many NHS staff will not report them. Others don’t know the reporting system exists. There’s no follow-up, as would normally be the case with a new treatment/medication/ vaccine still in the clinical trial phase. They’re not doing it because they don’t want to jeopardise the rollout of the vaccines, i.e. halt the rollout because people are dying or being made seriously ill.

Exactly.

“They’re dying within days or hours of the vaccine, not months.

Most of the adverse reactions are not being recorded because many NHS staff will not report them. Others don’t know the reporting system exists”

How do you know this?

Why do you say the vaccines are still in clinical trial phase? They have all been through clinical trials and been approved by the relevant authorities.

“Why do you say the vaccines are still in clinical trial phase?” Because they are?

https://www.google.com/amp/s/www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/science/coronavirus-vaccine-tracker.amp.html

I think if you read the article carefully you will see that the vaccines in use in the UK and USA (Pfizer, Moderna, AZ, Johnson and Johnson) have all completed their phase three clinical trials. There are of course many other vaccines still undergoing trials but they are not in use. Then there are the Russian and Chinese vaccines which have a slightly dubious status but are not in use here.

https://www.biopharma-reporter.com/Article/2021/03/03/Inside-the-Pfizer-BioNTech-COVID-19-vaccine-trial-Insights-on-speed-agility-and-digital-development

Read this carefully, the Pfizer one isn’t finished yet……

Oh do keep up.

the clinical studies for all drugs and vaccines are listed on http://www.clinicaltrials.gov

For the coronavirus vaccines, none have completed. Some have met their primary endpoints, but none has had full follow up for duration of efficacy and longitudinal safety data. We won’t get that data until 2023. The studies are ongoing.

All approvals at present are emergency use only, because we are in a “pandemic”.

Sophie your reply is succinct with a reference added. I wonder if MTF will bother to read/understand your reply?

Thanks for this. I admit I had not realised that the studies continued with monitoring of long term safety of participants (learning things like this is one of the major reasons I take part in these debates).

However, the fact remains that the trials have gone through a very significant stage with excellent results. Tens of thousands of participants have taken part in placebo controlled RCTs. The trials have been written up in peer reviewed journals and accepted by organisations such as the FDA, MHRA and EMA. Presumably the participants now know if they had the placebo. So from now on they are no longer RCTs. It is now a question of monitoring those who had the vaccine. This joins all the other monitoring of the vaccines in real life use which is going on round the world.

Obviously the remaining part of the trials are there to pick up long term safety and efficacy problems. We can never be certain that any intervention doesn’t have long term consequences, just as we can’t be certain of the long term consequences of getting Covid. And there is no obvious definition of what long term means. How long do we go on saying it is a trial? The FDA has set a limit of two years but this seems to be arbitrary. Historically any safety problems with vaccines have occurred within two months of taking the vaccine.

In any case, most of the concerns raised by the people in this debate seems to be about short term safety. LMS2 wrote that “They’re dying within days or hours of the vaccine, not months.”, yellow card or VAERS reports are based on events within a few weeks of taking the vaccine. The trials as done so far will have picked up any safety concerns in that timescale and should address these concerns.

May have been posted elsewhere, but this is an excellent video of a recent Texas Senate hearing on a proposal to introduce legislation to prevent compulsory vaccination and discrimination against unvaccinated people.

Testimonies are given by medical practitioners regarding VAERS data, therapeutic treatment of covid symptoms, the benefits of natural immunity over vaccine acquired immunity, the emergency use status of the covid vaccines and the risks of vaccinating people who already have natural immunity, and/or children.

47 minutes long but well worth setting aside the time to watch it.

https://tlcsenate.granicus.com/MediaPlayer.php?view_id=49&clip_id=15926

All previous corona vaccines failed at the animal trial stage and this experimental no-liability profiteering vaccine, still in stage three of the trials is being pushed by Big Pharma vaccine companies and complicit entities as hard as possible. Is this so that by the time the deaths and side effects become public knowledge (in spite of Govt and Media hiding the truth) it will be too late to turn back? This is not about health. If it were the Govt would have introduced anti-virals like HCQ and Ivermectin and High dose vit D Vit C and Zinc. It is all about profit and control. Profit for people like Gates, and control for Govts through vaccine passports. As for vaccine deaths Texas Senator Hall reveals some worrying figures in a country where vaccine adverse events are poorly reported – even so, the numbers are very disturbing: https://twitter.com/i/status/1392778728199970816

“Profit for people like Gates”

Actually, I don’t think profit is the key driver for Gates.

It’s something potentially far worse – a monomaniac religious fixation re. vaccines.

Gates has a mental disorder. His crappy Windows was so tortured by computer viruses, he’s lost his mind and is on an insane mission to eradicate viruses in the real world, not fully considering that in the biological world we actually need viruses. They are not a bug.in the system, they are a feature.

True re previous corona vaccines and gain of function trials – I don’t want to be like the ferrets.

Here we go – divide and rule. All the refuseniks will be responsible for the ratcheting of even tighter and more miserable restrictions.

Straight out of the Totalitarian playback. Next we’ll be banned from everywhere.

“Just a few troublemakers spoiling it for everyone”.

I wonder how many people in government, not just in the UK, are literally in the pay of Big Pharma and have an incentive to push the vaccines.

Here’s one place to start:

https://www.conservativewoman.co.uk/friends-and-allies-the-gates-foundation-and-british-scientists/

Friends and allies: The Gates Foundation and British scientists

It’s now happening what Profs Gatti&Montanari started to warn of over a decade ago: accepting the HIT myth will lead to this and that myth had and has solely that purpose.

At the risk of upsetting Lockdown Sceptics who don’t like terms such as ‘R number’ and ‘Herd Immunity’, the minister responsible for the statement in bold is talking tosh. The point about Herd Immunity is that a small number of non immune individuals cannot spread infection.

This of course assumes the vaccines work as vaccines should work.

Consider, at the start of an outbreak, that an infected person infects 3 other people (i.e. R0=3), then when 70% of the population are immune only 30% of 3, i.e. 0.9 people can be infected. Any outbreak will be small and cases will decline quickly.

I don’t think it is that simple. Is it?

No vaccine is perfect, so the 70% are still somewhat at risk.

There seem to be a wide difference of opinion as to how many people need to be “immune” before R is less than 1. I have seen everything from 60% to 90%.

The key concern has always been that the NHS should not be overwhelmed. 30% of the population is quite enough to do that.

As always with this virus – we don’t know what is going to happen.

The 70% may or may not be at risk, but vaccination must remain a personal, private medical choice

Define “overwhelmed” and explain at which points the NHS has been overwhelmed

“We don’t know what is going to happen” Well we’ve got a pretty good idea based on the real world evidence so far, which has tended to contradict modellers’ predictions. We know what is NOT going to happen, which is that NPIs will suppress the spread and that govts can control viruses by fiat

Many of the 30% may be immune to covid anyway

Easily found, the NHS is ‘overwhelmed’ most years , but last year and this has not been one of them.

It works at capacity most years, in certain areas at certain times of the year. Partly by design. Having a massive amount of spare capacity isn’t necessarily an overall good for public health. Overwhelmed is a strong, emotive term that for most people conjurs up images of bodies piling up.

By any reasonable comparison, the NHS is under-provided with beds (a long time bone of contention). This has been made worse by the thinning of bed numbers for distancing purposes.

And yet, at the worst of the winter infection season, it wasn’t ‘overwhelmed’.

This is a good article by Iain Dale about NHS bed numbers, and the lack of them:

https://www.iaindale.com/articles/its-time-to-reverse-the-decline-in-nhs-bed-numbers-updated

It’s Time to Reverse the Decline in NHS Bed Numbers (UPDATED)

8 Mar 2020

“If you look at the number of hospital beds per 1,000 of population, Britain has 2.54, just above Denmark (2.5) and Sweden (2.22) at the bottom of the EU league table. Germany is top with 8,0, Austria in second on 7.37 and Hungary third on 7.02. France has 5.98.

It is geriatric beds which have experienced the most serious decline, with the advent of the policy of getting older people out of the NHS system as soon as possible. All parties have bought into this, on the recommendation of the medical experts. That policy could soon come back to bit them if the Coronavirus crisis gets as bad as many people think it will.”

It’s a decline that’s been going on for decades, made plain each winter. That’s the real shortage. And it’s not due to the lack of money. I’ve seen too much waste in the NHS to believe that, with people on very good salaries, doing the bare minimum, and whose absence wouldn’t be noticed.

There’s too many who regard NHS funding as “other people’s money,” and waste it accordingly.

LS 2nd January 2021

Yes you’re right. We should probably use the term effective immunity. 70% vaccinated does not necessarily mean 70% immunity. However, there are a significant number of individuals who have immunity from natural infection.

I used R0 of 3 and the 70% figure as an example. I don’t know how the minister would define “small number”.

The calculation seems to be extremely complicated and full of unknowns.

I agree the minister was overstating the case by saying “The risk is that a small number of [unvaccinated] idiots ruin it for everyone else” but I think he/she might reasonably have said something on these lines: while a significant number of adults are not vaccinated there is always a risk of a substantial outbreak

…which has to be weighed against the longer-term risks of novel vaccines that haven’t been through Phase III and for which Phase III may never be properly completed now that there is talk of unblinding the participants. Also, many groups that were completely excluded from the vaccine trials are now encouraged to take it. We didn’t do this for flu, and excess deaths during flu seasons in the not too distant past (1999-2000) have been similar to the recent April and winter spikes.

Immunity from past infection is very well documented and virtually certain. There will always be outriders. Anyone with a T cell immune response can’t be infected.

are not vaccinated or have no natural immunity from having had the virus…

Funny they never say that.

Funny they don’t fund T cell testing with their imaginary billions to find a decent estimate of natural immunity.

Yes. If they were honest about it they would introduce proper T cell examinations as a precursor to offering an experimental jab. It would support the firm that manufactures the relevant kit (one of them based in Oxford, I think), and reduce the risk to each individual involved. I’d rather donate a relevant blood sample for that rather than taking on something novel that might be useless to me, e.g. Dishing out dodgy contracts to various firms under the current problem is par for the course for this lot, unfortunately.

They know they would get the wrong answer

The NHS should be scrapped if the population’s freedom is scrapped to prevent it’s obvious failings becoming too obvious to ignore.

“70% are still somewhat at risk”

At what risk from a pretty ordinary virus that has less impact than the vast majority in living memory?

“we don’t know what is going to happen”

True. Which is why all the failed modelling sources should be ignored, and we should trust to a simple assessment of probabilities based on existing data and careful analysis of it.

I have found that gives me accuracy of prediction that is many orders better than all the computer gaming attempts and the garbage generated by SAGE.

In fact, SAGE predictions have been so comprehensively wrong, that the odds of the errors being random is difficult to sustain – suggesting an inbuilt bias. Quelle surprise!

So given that you have just admitted that the vaccines are not effective:

“No vaccine is perfect, so the 70% are still somewhat at risk.”

plus in our other conversation we established that what is being done is experimental in nature, dangerous and causing real world harm, with injuries and deaths already on an unprecedented scale, does it not make sense to treat the minority who actually get sick with Covid19 with highly effective drugs like HCQ and Ivermectin, to use Vitamins D and C and Zinc in the Nursing Homes as preventative medicines and make use of the out of patent, cheap, effective, near harmless treatments we have in the shelves of every self-respecting hospital on Earth, rather than inject the entire nation/world with experimental, novel vaccines using all sorts of weird delivery systems and hijacking a person’s cellular processes for no good reason, and all the short, medium and long term serious health risks that come with these injections?.

Also, taking into account the totally average IFR of 0.15% for Covid19, why are you still coming on here to promote this clearly evil, abhorrent and dangerous method of treating a bit of seasonal respiratory disease, aka Coronavirus?

Doctors For Covid Ethics agree with you on that actually, the vaccines are not effective:

COVID Vaccines: Necessity, Efficacy and Safety

Doctors for Covid Ethics

https://off-guardian.org/2021/05/05/covid-vaccines-necessity-efficacy-and-safety/

There is also natural immunity. I know Sage likes to pretend it doesn’t exist, but there’s no reason for you to join them.

“No vaccine is perfect, so the 70% are still somewhat at risk.”

But not of dying or being seriously ill, according to the data so far, but we will know more next winter.

“The key concern has always been that the NHS should not be overwhelmed. ”

Not heard that little gem in a while…. NHS never was overwhelmed, in fact they cleared it out and ran it at 70% capacity, and left the Nightingales empty , freeing up staff for fun tic tok dance routines and pizza parties.

So then, a few people can’t actually spoil it for anyone if no immunity is conferred by the vaccines.

Can’t have it both ways.

When this whole thing started, the threshold for herd immunity was at 30% immune. Now it somehow got bumped up to 70% vaccinated. Overnight, with no justification, and everyone acting like that’s how it’s always been. So sorry if i don’t buy this 70% number, especially since the number of immune people is well over that by this point.

if the vaccinated provides full immunity then 70% vaccination would be enough. But that ignores natural immunity already acquired.

70% immunity however it is acquired (natural or vaccine) should be enough particularly since a proportion of the population (10%-20%??) have prior T-cell immunity.

Not sure what you mean. Unless we have a particularly infectious variant then the probability of a large outbreak in a 70% immune population is small. Even, when people are living together in close proximity in the same houses not everyone in the household gets it.

Remember, this assumes that the vaccinated 70% really are at least 90% immune. (63% effective immunity)

Please don’t interfere with The Agenda using mere facts

The idiots are the ones pushing for universal vaccination with an imperfect vaccine that will almost certainly result in vaccine escape and very rapid growth in case numbers once vaccine escape variants take over (because everyone has a similar immune profile).

Those idiots will be responsible for the deaths of many thousands of our most vulnerable.

All they needed to do was vaccinate the most vulnerable, but they fluffed it with their hubris driven goal to vaccinate the world.

They aren’t ‘idiots’. They are knowing perpetrators of evil and deception.

If immune escape is going to be a problem, I’d suggest we’ve already gone too far.

In fact, like it or not, we might now be better off going for full vaccination (ASAP). According to GVB the variants will develop via immune escape and infection of asymptomatic cases (with less than optimal antibodies). It is they who will drive the ‘new’ AB resistant variants. Seronegative individuals will still have their innate immunity but there is the potential for a serious outbreak.

The concern is that ‘Original Antigenic Sin’ will result in infection with a vaccine escape variant will result in worse symptoms for a vaccinated individual compared with someone similar but naive to sars-cov-2.

We don’t know if this will turn out to be a problem or not, but we’re gambling with the health of millions of people worldwide based on the assumption that it won’t happen.

Yes I agree that the vaccinated will probably take the worst hit, but the likely route to the vaccine escape variant (according to GVB) will start with an infection to a previous asymptomatic case from a vaccinated person, i.e. the leaky vaccine allows onward infection.

I don’t understand they idea that asymptomatic cases will drive anything. It seems that an asymptomatic infection is a dead end for the virus. The person who encounters and is asymptomatic has an immune system response that blocks illness which means the virus cannot be spread to anyone else and that means these folks cannot make new variants but they do add to the pool of the immune making spread more difficult.

That’s a good point — the missing information is that asymptomatic cases aren’t devoid of symptoms. It took me a while to work this out as in every other instance I’ve seen the word ‘asymptomatic’ it means without symptoms.

In the case of covid it appears that ‘asymptomatic’ includes those with minimal symptoms.

Those with minimal symptoms are capable of spreading covid.

Then they wouldn’t be asymptomatic, would they?

That number is absolutely tiny to the point of being negligible. As a result its so small its not capable of ‘spreading’ anything.

Asymptomatic means healthy surely. Without symptoms you do not have the virus so can’t pass it on.

Check out Dr Geert Van Bocche.

The total idiot is the arsehole who made that remark. A fairly typical example of the morons who comprise this corrupt government of liars and ignoramuses.

We need to continue lockdown to protect those who choose not to get vaccinated.

We who choose not to get vaccinated make it very clear that we choose the risk to get infected!

Yes I don’t want or need anyone to protect me.

Especially as the risk of from infection is lower than the risk from being jabbed.

I would be happy to sign a paper confirming that, and even one to bind me into paying for my own Covid treatment in case I got it and needed hospitalisation in exchange for continuing to be able to reject the gene therapies.

I couldn’t care less what politicians, ‘scientists’, presstitutes and other corrupted gene therapied zombies think of me and my actions or non-actions.

Being called a denier, refusenik or idiot by that lot is actually a badge of honour for me, which I shall wear with pride.

Meanwhile … Texas had an indoor boxing event with 74,000 fans on 8th May. No vaccine passports, no masks, no social distancing.

A great reminder of how framing the debate via the media is how they plan to manage this here.

Hmm – May 8th

It’s a bit early to be declaring it a success. It probably is – but let’s make sure shall we. Don’t forget Toby Young, Yeadon et al got their fingers burned last year following overly optimistic predictions.

Agreed, but it is so grossly wrong that members of sage et al can make monstrous inaccurate forecasts and many many errors and the MSM just shrugs its shoulders. But if a sceptic makes so much as a tiny error, they are hounded to oblivion (slight hyperbole but you get my drift, I hope).

As someone pointed out earlier, we are in an abusive relationship with the government.

Well – it looks like things were back to a normal level until vaccines created a higher peak of deaths in January.

For a cold? The government, SAGE and the rest are comprised of unethical, ignorant, lying, unprincipled, dangerous f*ckwits. What happened to bodily autonomy and consent?

Still not having any blasted vaccination, for anything, ever.

It’s more than a cold for many, and more like a serious influenza infection. For those who’ve had flu for the first time, you’ll know it’s not something you can just shrug off or take a couple of Lemsip Max and go to work with, whatever the ads used to tell you.

If there was a £1000 on the floor in front of you, you wouldn’t care. If you were on a plane and you thought it was going to crash, you wouldn’t care about that either.

You’re absolutely right – I’ve always been acid towards anyone who calls a cold ‘The ‘Flu’.

But, having experienced bad viral infection, and being vulnerable, I would never contemplate locking up the well as a solution to anything.

It’s barmy by any criterion.

Rick, with some people,if they sneeze once, they’ve got a cold, twice, they’ve got the flu and if they sneeze 3 times, they have got pneumonia!!!

A sensible doctor once explained that what a lot of people call “the flu” is actually “rhinitis with pyrexia” ie a cold with a temperature which may be caused by numerous viruses. Actual flu is an order of magnitude worse

The point is that not all people manifest the same severity of symptoms for the same disease. For an old person, or an unhealthy vitamin deprived over stressed individual, then a cold, flu or corona are going to be bad.

Amen to that.

My wife and myself had flu in late 2018(Covid 18?) and even to stand we had to psych ourselves up and use all our strength and we also became dehydrated and lost half a stone.

IT’S CALLED THE FLU!

To be a bit pedantic, ‘flu is not caused by any ‘coronavirus’; it comes from a different structure. A large proportion of ‘common colds’ are actually caused by established coronaviruses, like 229E, OC43, HKU-1 etc, but have never been labelled ‘Covid-xyz’. Quite a lot of language fraud going on, and manipulating people via dodgy education, and being “selective with the truth”. That is how many politicians operate.

I take your point, JK.

I agree with this DM comment …

‘DM who was this minister that called people who haven’t been vaccinated for whatever reason, idiots? Was that even said, if so why have you omitted their name? Why is the DM using communist style disparaging labels like “Refuseniks” to try and drum up hostility towards people who haven’t been vaccinated?’

That the so-called civil servant, paid for by tax payers money, who that said that, needs to be named and shamed! They are SO desperate now, that their evil, sick agenda isn’t going the way they planned. Here’s an idea. How about addressing all the deaths and ADRS that have occurred since jabbing the poison into the unwitting population?

We wondered on here back when Hitchens and Swayne capitulated to the agenda, what were their motivations? As both insiders, I’d suspect they knew this was the plan all along. They knew how far they’d go, and this is now step one.

They’ve got their scapegoat primed. Can only imagine the forthcoming media hysteria to be directed at the ‘idiotic refuseniks’.

I wouldn’t bet against that nasty quote being a creation of our beloved media. Sources say blah, blah, blah is not even worth reporting as ‘news’ and yet…

All the airports were open with flights from all over the world landing and taking off throughout 2020 … this was happening at the height of this supposed ‘deadly pandemic’ – there were people from all corners of the globe coming in and out of the country … no vaccinations available at all back in 2020. Now with most of the vulnerable vaccinated suddenly we’re supposed to believe that a small section of unvaccinated people in the UK are a threat to the entire population?

Ridiculous.

From three weeks to flatten the curve to vaccine idolatry (see “Vaccine Saves” on Chirst the Redeemer statue in Brazil”) to stigmatising the unvaccinated. This is how far this nation has degenerated in 14 months! Shame on the government ministers and shame on the media and shame on those keeping silent.

still don’t have long term health data for the vaccines. shouldn’t even be offered to people unless they are hyper-vulnerable

certainly shouldn’t be giving to kids (some of whom will die) to protect a few people in care homes. I’d hoped society had moved on from child sacrifice

I’ve called it a looong time ago. First it starts with “vaccines are optional”. Then it goes to “we need 70% of people to take the optional vaccine”. And it ends up with “if the last 30% don’t take their vaccines, they’ll anger the other 70%… it would be a shame if you got lynched in the street for not taking it, so better just take it, ok?”

The 70% threshold they came up with for “herd immunity” had nothing to do with immunity and everything to do with how many people does it take to strongarm the rest into compliance.

Absolutely brilliant summing up, Cristi!

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41564-020-00789-5

“ADE has been observed in SARS, MERS and other human respiratory virus infections including RSV and measles, which suggests a real risk of ADE for SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and antibody-based interventions. “

“Going forwards, it will be crucial to evaluate animal and clinical datasets for signs of ADE, and to balance ADE-related safety risks against intervention efficacy if clinical ADE is observed.”

a work in progress

“…a small number of idiots ruin it for everyone else.”

Is that what they said to Francis Oldham Kelsey of the FDA? She refused to approve Thalidomide going to market as she found the application lacked sufficient evidence of safety through rigorous clinical trials (https://tinyurl.com/yrbw99ry).

Fast forward to Covid-19. We have lack of evidence of safety through rigorous clinical trials SQUARED.

“…a small number of idiots ruin it for everyone else.”

They’re known as ‘the government and SAGE’.

If they incite real violence over a nudge, we would be teetering on all out civil war.

The establishment need to be “nudged” towards liberty for all.

Bob’s illustration has one flaw – I don’t see Johnson as having the physical fitness to walk up and down a mountain trail.

Not a flaw perhaps it’s a veiled acknowledgement that we will never reach the “old normal tea rooms”

When he was in hosp last year, allegedly with C19, his weight was ‘accidentally’ published, from which one can work out that he must have been one of the grossly overweight people, being more vulnerable to it in the first place. Made me wonder, if he was a fit, active, intelligent politician, the outcome would have been different.

It seems to me equally possible that most of the hospitalisations worldwide since about a year ago could perhaps have been avoided if the science/medical community had been given the right organisational help to find non vaccine prophylactics and treatments.

“The Risk Is That a Small Number of Idiots in Sage and Government Ruin The Country for Everyone” Says Happy in the Haze

For a health secretary, Hancock is a bit of a plank, isn’t he? Doesn’t he read the information on the vaccine packs? “This jab will not stop you getting covid, nor will it stop you passing it on. It might reduce some symptoms.”

So, Hancock, you plank: it’s the jabbed who will be spreading it around unknowingly. Anyone else with symptoms will (a) stay at home or (b) be shunned by all and sundry.

“selective with the truth” is a useful observation, with those under investigation etc.

Theyre doubling down with the vaccinate or else rhetoric folks. Hilarious actually. They’re all under pressure by the great powers to do a better job. Lets make it harder for them. Do not give in. They’re weak pathetic sociopaths.

I don’t need protecting, you horrible, slimy hypocrites.

So the unvaxxed are idiots? That’s everyone under about the age of 40 then and quite a few above that. This psyops stuff is getting really boring at this point. And very blatant.

I’ve not been around for a few days but, if we accept that the Indian variant is more contagious, has this resulted in increased hospitalisations or, more to the point, deaths ?

NO!!!

I’m not sure there’s even any conclusive proof that it’s more contagious. Let’s fact it, they needed an excuse to keep restrictions around and force the reluctant to be vaccinated, so they can bring in vaccine passports. The “Indian Variant” is just a means to an end.

“When the debate is lost, slander becomes the tool of the loser” Socrates may or may not have said this but whatever, it rings so true.

Update on a potentially ‘new’ vaccine. Sanofi/GKS ‘vaccine’ based on a Sanofi flu virus started its delayed Phase 2 trials that take 1 year to complete. Because GKS has a particularly aggressive shareholder they are desperate for some good news for their share price. So they announced that the Phase 2 trials had performed so well to date, 1 month in, that they were going to go forward with Phase 3 ( 3 years to complete) and hoped to get emergency approval in Q4. Happily the share price went down.

However another rushed exercise with no actual numbers released and as most of the trials of 720 people were in the US with rapidly declining prevalence its likely the absolute risk reduction figures are negligable.

They have admitted that the ‘antibody’ creation in Phase 2 has not been as high as hoped, but apparently not many have died in the last month.

Small vaccine catastrophe, not many dead.

Those who are dead are, however, reported to be 100% dead.

I am struck by how much space in this thread is devoted to a diversion about herd immunity and vaccines.

The essential point is that this unmoderated virus, within a sane historical perspective, nowhere nears justification for the sociopathic measures imposed upon the population.

And all it took was one government sponsored troll arguing the far end of a fart about stats. Still no reply yet for them to supply evidence of death by covid-19.

Exactly,

now why would so much energy be put in to divert from the simple obvious truth ?

What happened to the belief of

“I might not agree with what you say and do but respect your right to your view and decisions”?

Mail on line, quoting a Tory spokesperson: “Small number of idiot vaccine refusenicks putting Covid recovery at risk.

I have had my 2 jabs (no ill effects, as yet) but if people don’t want the vaccine then their wishes should and must be respected.

“The Risk Is That a

SmallLarge Number ofUnvaccinated Idiots Ruin It for Everyone Else,” SaysMinisterSensible PersonWho said this and why haven’t they been sacked yet?

Just thought I’d add this, too:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minimal_group_paradigm

You need to be very careful with things like this.

“The risk is that a small number of idiots ruin it for everyone else.”

Well, that will be a change from the large number of mask-wearing, hand-gelling, stay-at-home, idiots ruining it for everyone else, as they have been for the past year.

BRILLIANTLY PUT.

“The risk is that a small number of [unvaccinated] idiots ruin it for everyone else.”

Rather than name calling, why doesn’t the senior minister just publish the proof that non-participation, in the programme of experimental injection of genetically-engineered biological agents, cannot be a rational decision?

Let’s not.

Would you expect to keep your job if you called your manager an “idiot” in a thinly veiled threat? Even if the identity of this low-life scumbag was revealed, we know there’d be no repercussion for him/her demonising innocent members of the public like this.

Yet I fully expect such language will become common, and the public will feel completely free and entitled to treat us the same way. I believe he/she is deliberately changing the dynamics and mood of the public at a time when everyone is in high spirits about returning to what they hope will be the old normal.

The minister might even be fictional, an inventional of SAGE’s behavioural psychologists, using the job title “minister” to suggest an authority figure.

Yes absolutely. This is undoubtedly the beginning of another ‘behaviour nudge’ which, as you say, could be being tested via a fictional minister.

Rightly or wrongly, from a rhetorical point of view “a cleaner at the Palace of Westminster said…” doesn’t work as well as “a minister said…”

Questions for those legal eagles amongst us.

At what point would accusing the unjabbed as being responsible for any oppressive Government measures be considered a hate crime?

At what point would accusing the unjabbed of being responsible for any oppressive Government measures be considered ‘coercion’ under the Nuremberg Code?

I don’t need to be lectured, I just ask how far can this go before it crosses these boundaries.

Considering that a lot of BAME and Muslim people won’t be getting the “vaccines” – either due to past medical crimes against humanity against minorities or due to religious reasons, I think we can build a pretty good coalition with them.

We can, at a push, even use the Woke to say this is racial discrimination. It would probably work.

“The Risk Is That a Small Number of Idiot ministers Ruin It for Everyone Else,” Say unvaccinated

there, fixed it for you.

Actually it would seem that it’s most of idiot ministers. But good comment anyway.

“unvaccinated” is problematic, since (at least some of) these genetically-engineered biological agents are not vaccines. Plus, of course, almost all of us have had some kind of vaccine.

Anyway Curzon seems to have

plagiarizedtaken inspiration from you!https://www.bournbrookmag.com/home/ministers-not-the-unvaccinated-are-ruining-it-for-everybody-else

The risk is that a small number of megalomaniac f*ckwits, desperate to turn Britain into a totalitarian state, infect the minds of the “great” British population.

Here we go – right on cue – it’s all our fault (apparently) that Lockdown Heavy might get extended (despite the Government’s firm promise it wouldnt) – all because the lady (and the gent) won’t get jabbed. So far so predictable of the Government.

DR MIKE YEADON | FULL SPEECH | CANTERBURY FREEDOM RALLY | MAY 2021 You MUST WATCH and not listen to Neil Ferguson

https://odysee.com/@FwapUK:1/mike:9

WTF happened to the coverage of the masses of Freedom Rally’s all over the world? Not least London and the rest of the UK. The lack of it is one of the more sinister elements of this whole sorry pile of SH1T. ‘Telegram’ covered loads of marches all over the world. Nowhere to be seen elsewher. Not even on LS that I’ve been able to find to date. Did it not happen? Did I imagine it?

A member of SAGE says that the ban on indoor gatherings should never have been lifted and might, at some stage, need to be reimposed.

How is an indoor gathering different to lots of people in a supermarket?

So very depressing, no actually – anger inducing.

So many young, healthy people signing up to get themselves stabbed, all posting on Facebook accompanied by so many YAYs and Well Done’s and love n care emoticons.

So ignorant, so stupid, so gullible. So lacking in ability to question, to assess truth and facts vs lies and propaganda. So devoid of common sense. So uneducated in basic biology. So dumbly compliant.

Makes me think the human race deserves all that is coming.

It took many years for the doctors at the Centre for Epilepsy to adjust and readjust my brother’s medication to the point where his seizures at last became infrequent, and until a few weeks ago he had been seizure-free for well over a year. He’d become more confident, sometimes almost forgetting he had this terrible affliction. He’d also come through treatment for prostate cancer. He was looking towards a holiday.

Then they gave him the jab.

In the fortnight since, he’s had two seizures. Over the decades my brother has suffered, among other injuries, a fractured shoulder, two broken wrists, one broken arm, and extensive and painful bruising, all acquired during seizures, for which he has no warning, and which can be quite violent.

His doctors have stopped the second jab while they ‘look into it’. The last I heard was that they’re ‘looking into’ a different vaccine. I have begged him not to have any more jabs but, surrounded by carers and ‘medical professionals’, it will be done before I know it.

My blood is boiling with hatred for the Devils running this massive transfer of wealth to the filthy-rich globalists, with the absolute compliance of those we elect to look after the interests of our country and our people. I hope that Hell has special infernos for them all.

I am a “vaccine” refusnik. I am not “hesitant”. I understand scientific arguments. I can read. I can weigh up arguments and counter-arguments. I can smell a steaming pile of b.s. from a mile off. I do not consent to participating in a mass experiment, purely to amuse our so-called leaders. Call me an idiot if it makes you feel better about yourself. I will not take these unnecessary drug cocktails. Period.

Please read Dr. Peter McCullough’s recent remarks on the vaccinated and unvaccinated. 60% of his recent COVID patients who sought treatment for COVID, were VACCINATED, with two doses of COVID vaccine. There is a 1% difference between the vaccinated and unvaccinated getting COVID according to Dr. McCullough, in other words the vaccines are meaningless. He worries next fall winter, there may be a massive increase in deaths of the vaccinated due to their immune systems over reacting and killing them. He isn’t the only doctor sounding the alarm.

As usual, complete lies from Govt.

It’s irrelevant if anyone not interested in vaccination passes.

Forced vaccinations are coming.. and then they will be regular.. boosters.. a money spinner for sure.. digital ID.. but they will (if not already) be weaponized.

Here’s just one of the 4000+ deaths reported on the VAERS system so far:

VAERS ID 0913143-1 “Vaccine administered with no immediate adverse reaction at 11:29am. Vaccine screening questions were completed and resident was not feeling sick and temperature was at 98F. At approximately 1:30pm the resident passed away.”

Dead in 2 hours.

But i’m sure it was just a coincidence.