by Derek Winton

Historians are sure to pore over this ‘unprecedented’ period for centuries to come. It is my belief that in the fullness of time, they will come to regard our response to the Sars-CoV-2 virus as monumental folly. In particular they will be bewildered by the role of deeply flawed computer modelling in triggering a chain of events that fundamentally, and perhaps catastrophically, damaged western society.

I should outline my own credentials on this subject:

I have an MA in Philosophy and Mathematics and a MSc in Computational Intelligence. I have been developing software professionally for more than 10 years and also have experience working with the code produced by academic institutions. In this particular instance I am a contributor to the official online software repository for the Imperial Model. I have submitted hundreds of lines of comments that explain the functioning of the model and these comments were accepted by the Imperial team.

Background

To put the role of the Imperial Model in the proper context, it’s worth reminding ourselves of the situation as it stood in February 2020.

There had been rumours for a few months of a new virus in China. Footage of Chinese citizens being forcibly dragged from their homes by Government agents in hazmat suits and locked in hermetically sealed vans. Tales of doctors who, after sounding the alarm, mysteriously disappeared.

Viruses had emerged in the recent past though and their impact had been relatively small outside of Asia. Many in the West watched with interest more than deep concern.

Then the virus arrived in Italy and events took a darker turn. Footage of overflowing ICU units, ventilator shortages, exhausted doctors. People were dying horribly, in the West, and in large numbers. Then Italy did something unprecedented in a western democracy. It locked down.

Soon the rest of Europe started to implement lockdown measures of their own. Ireland then Denmark then Bulgaria. In a few days almost every country in Europe and many more around the world had started to implement a policy that until that year had never been used to deal with a pandemic.

Two countries chose a different path. In line with the plans they had in place to deal with pandemics, they chose to build capacity and mitigate the effects of the pandemic while building ‘herd immunity’. Those countries were Britain and Sweden.

The UK’s Chief Medical Officer and Chief Scientific Officer, Chris Whitty and Patrick Valance chose, with the apparent full backing of the Government, not to panic and proceeded in line with our well-developed pandemic strategy based on hundreds of years of clinical experience.

Then one of the members of SAGE, Neil Ferguson of Imperial College, published a paper on the 16th of March predicting up to half a million deaths. That paper was then picked up by the media and the conclusions were duly published.

Public pressure mounted and just a week later the UK Government took the unprecedented step of issuing a stay-at-home order for the entire nation, describing the Imperial College model as the ‘gold standard’. Indeed from the report itself: “Results in this paper have informed policymaking in the UK and other countries in the last weeks” (Page 1 – Summary).

Some eyebrows were raised. Decisions of this magnitude should surely be subject to the highest level of scrutiny. People started to ask for more details on the model.

Peer review

The Imperial College team delayed publishing the code that underpinned the paper. A senior member of the team is quoted as saying:

Given the increasingly politicised nature of debate around the science of COVID-19, we have decided to prioritise submitting this research for publication in a peer-reviewed scientific journal and will release it publicly at that time.

Financial Times May 23rd 2020

The research hadn’t been peer reviewed. In other words no-one outside the small team of researchers who produced the report had checked it.

Documentation

Time was short though and this was an emergency. Peer review can take months and we needed answers quickly. Perhaps we could assume that this was a well-designed model with extensive documentation.

Except this statement was made on Neil Ferguson’s twitter feed:

Expertise

This was not necessarily cause for alarm. Research from Imperial College, one of our most august institutions, surely had the very best people working involved?

Now to cut off any accusations of ad hominem or ‘playing the man not the ball’, this is a question of expertise. The expertise of an expert is entirely relevant, indeed arguably it’s the only thing that is relevant. So let’s look at the qualifications of our expert. From Wikipedia:

He received his Bachelor of Arts degree in Physics in 1990 at Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford and his Doctor of Philosophy degree in theoretical physics in 1994 at Linacre College, Oxford.” [Emphases mine]

In an interview on the BBC’s Life Scientific (Timestamp: 6m 15s), Professor Ferguson conceded to not even having an A-level in Biology. As far as publicly available information is accurate, Professor Ferguson appears to have no formal training in computer modelling, medicine or epidemiology either.

Previous predictions

Formal qualifications are only an indicator of competence. The absence of a qualification doesn’t prove a lack of competence. Many people have a great deal of skill in a wide variety of fields but don’t necessarily have a piece of paper to prove it. Let’s instead look at the past performance of the Imperial College team.

Foot and mouth

Many will remember the slaughter of 6.5 million cattle, sheep and pigs in 2001 to contain an outbreak of foot and mouth disease, devastating the farming industry. This drastic measure was based on modelling by Professor Neil Ferguson.

Many within the farming industry thought that the measures were disproportionate to the threat posed, including Professor Michael Thrusfield of the University of Edinburgh who described the model as “not fit for purpose” and “severely flawed“.

Responding to the criticism, Professor Ferguson explained that they were “modelling in real time” with “limited data“.

Other epidemics

| Virus | Prediction / projection | Reality |

| BSE | “The Imperial College team, whose work is published on the website of the journal Nature, predicts the future number of deaths from vCJD due to BSE in beef was likely to lie between 50 and 50,000.” – Daily Mail “But Dr. Neil Ferguson, an epidemiologist in another group of highly respected researchers led by Dr. Roy Anderson at Imperial College in London, said the new estimates were ”unjustifiably optimistic.” His group published estimates a year ago predicting that the number of variant C.J.D. cases might reach 136,000 in coming decades.” – New York Times Oct 31st 2001 | A total of 2826 people have died from CJD over 30 years – National CJD Research and Surveillance Unit, The University of Edinburgh |

| Bird Flu ( H7N9) | “Last month Neil Ferguson, a professor of mathematical biology at Imperial College London, told Guardian Unlimited that up to 200 million people could be killed.” – The Guardian Sep 30th 2005 | “Since 2013 there have been 1,568 human cases of bird flu and 616 deaths worldwide from the H7N9 strain.” – The Express Dec 7th 2020 |

| Swine flu (H1N1) | “In 2009, Ferguson and his Imperial team predicted that swine flu had a case fatality rate 0.3 per cent to 1.5 per cent. His most likely estimate was that the mortality rate was 0.4 per cent. A government estimate, based on Ferguson’s advice, said a ‘reasonable worst-case scenario’ was that the disease would lead to 65,000 UK deaths.” Spectator 16th April 2020 | “457 people are known to have died during the pandemic in the UK as of 18 March 2010” – Independent review of the UK response to the 2009 influenza pandemic – gov.uk 1st July 2010 |

To be entirely fair, there is a distinction that is often lost in the reporting of scientific estimates between ‘prediction’, ’projection’ and ‘reasonable worst case scenario’, but this does in turn prompt at least two serious questions:

- When the ‘reasonable worst case scenario’ estimate reliably turns out to be several orders of magnitude higher than what transpires, what value is there in that estimate?

- Given the lack of scientific training of some sections of the media and the tendency to publish the most attention-grabbing statistic, is it responsible to publish these estimates without clear guidance on how they should be interpreted?

Code quality

Perhaps despite these high estimates, the team had applied lessons from previous epidemics and adapted the model accordingly. What can we say of the quality of the model itself?

For those without formal training, computer coding can seem like a dark art akin to black magic. But fundamentally every single computer program is a list of instructions carried out ‘mindlessly’ by a computer. The most important characteristic of a program is that it performs the task that it was designed to do. There is however another important consideration, namely the legibility of the code for human programmers. Two pieces of code can be ‘functionally equivalent’ in terms of the outputs they produce but can vary widely in terms of how intelligible they are to human programmers.

Over time, ‘high level’ computer languages have emerged that are much closer to the natural language of programmers than the language of the CPU. In addition, various best practices have been developed to ensure that computer programs can be easily read by the humans that design them. In a well-coded application a programmer with no experience of the particular programme should be able to read a section of code and quickly establish what is being done.

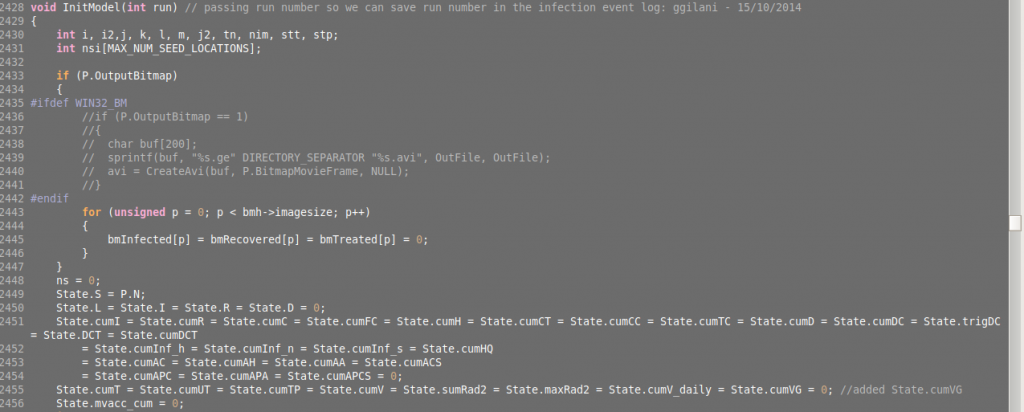

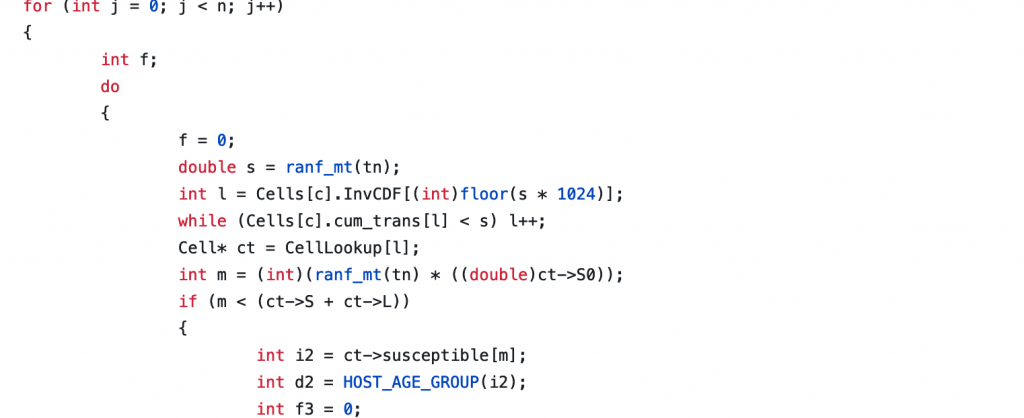

The following is a representative sample of the code in the Imperial Model: (lines 213 to 228)

I challenge any computer programmer to work out, without reference to the code repository, what is being performed in the above code.

Design

Even if the code weren’t easily legible that would not necessarily mean that the code performed badly. If the programme is well designed and coded correctly, a lack of legibility can be forgiven.

Again some context is useful in explaining this section.

Computer models have proven to be incredibly powerful in fields such as engineering where applying the well-understood laws of physics to simple systems can yield highly accurate predictions.

Modelling a pandemic is a fundamentally different type of challenge as it is essentially attempting to predict the future for a hugely complex dynamic system. This is analogous to predicting the weather, another hugely complex and dynamic system, or the value of the stock market. Two challenges that, despite billions spent on research, we still cannot do beyond an incredibly short time horizon.

When we attempt to model dynamic systems we step into the world of so-called chaos theory – the study of systems with extreme sensitivity to initial conditions. Many will be familiar with the so-called butterfly effect where a tiny change in air currents from the flap of a butterfly’s wings can, thanks to the complex interactions of billions of particles, result in the appearance of a tornado.

The nature of dynamic complex systems dictate that a single design flaw in the computer model, let alone an error in the code, will result in potentially huge errors in any predictions it makes.

As someone who has reviewed the core functions of the Imperial code line by line I am sad to report that it takes no account of one of the most important variables that we know is at play: “seasonality” (the interaction of the season with respiratory viruses – the reason we have a surge in them every winter).

Predictions for COVID-19

Perhaps, despite all of the concerns outlined above, the Imperial Model is an effective predictor of deaths from COVID-19. With the benefit of hindsight, let’s compare the predictions for 2020 with the reality.

UK

The Imperial Model predicted ‘up to’ 500,000 deaths in the UK. We recently officially passed the grim milestone of 100,000 COVID-19 deaths so the 500,000 prediction is out by 400%. This prediction was, to be fair, based on a scenario of no mitigation. One could of course argue that the death toll would have been much higher without the lockdown. Unfortunately, in the case of the UK, that statement is unfalsifiable. But what did happen to countries that didn’t lock down? Well, as almost every country in Europe did lock down it it difficult to find a true ‘control’. Except one.

Sweden

A team of Swedish researchers applied the Imperial Model to their own nation and projected an overwhelmed health service and 96,000 deaths.

Sweden as of today has recorded 12,569 deaths. The projections were out by 700%.

It has become a standard response to any mention of Sweden that they have a higher death rate than comparable Nordic neighbours. This is a fair point with regard to optimal strategies for a given country but one that is irrelevant to the case at hand.

To state the case as plainly as possible:

If the Imperial Model were fit for purpose as a predictive tool, Sweden would have many times more deaths than they do. Given that this is not the case, there is only one conclusion that can be drawn.

Conclusion

When (if!) the dust finally settles on the Coronavirus pandemic it will be difficult for future historians to conclude anything other than the following: We abandoned our carefully planned and rehearsed pandemic preparedness plans in favour of an experimental measure on the basis of non-peer-reviewed, undocumented, obscure, predictively inaccurate modelling, using a design that leaves out one of the most important variables involved, created by an expert with apparently no formal training in computer modelling or epidemiology and a track record of very high over-estimates of disease mortality.

Prediction is an incredibly difficult business. That said I am absolutely confident that, in years to come, those historians will shake their heads and wonder: “What were they thinking?”

Derek Winton is the prospective parliamentary candidate for Lothian Region for the Reform UK Scotland in the forthcoming Scottish Parliament election on May 6th. You can follow him on Twitter at @derekwinton.

Donate

We depend on your donations to keep this site going. Please give what you can.

Donate TodayComment on this Article

You’ll need to set up an account to comment if you don’t already have one. We ask for a minimum donation of £5 if you'd like to make a comment or post in our Forums.

Sign UpCareful What We Wish For

Next PostLatest News