The U.K. Net Zero Carbon policy (UK NZC) is a Government policy offered as a solution to a problem that involves a range of academic disciplines. As well as being complex, the science of anthropogenic carbon-based global warming is controversial. Although some climate scientists insist that it is ‘settled’, there are many dissenters, as an internet search or a trip to a good bookshop will confirm.

The multi-disciplinary nature of climate science coupled with differing views among experts makes it almost impossible for a layman to follow the arguments, let alone assess the evidence and come to an informed opinion. Despite these apparent difficulties, I’ll argue that it is possible to establish a simple framework that can clarify complex questions – in this case, “How likely is it that UK NZC will be an effective response to global warming? – without requiring specialist knowledge. I also show how the approach can be used to identify, measure and illustrate differences of opinion.

Start from a small number of statements that make up the Net Zero commitment.

- The Earth must actually be warming.

- The warming must pose a genuine and serious threat to life on Earth.

- The warming must be man-made. Specifically, it must be caused by excess carbon dioxide in the atmosphere arising from human activity.

- The U.K.’s NZC policy must bring about a meaningful global reduction of atmospheric carbon. That is, it must either make a significant reduction in its own right, or it must set an example that persuades other countries to reduce their own carbon emissions, to a degree sufficient to stop the warming.

For UK NZC to be effective, statements 1-4 must all be correct. If any one of them is false, the policy will fail, either because it doesn’t lead to sufficient carbon reduction, or because the policy wasn’t necessary in the first place.

The next step is to define a view (with respect to statements 1-4) as a set of probabilities p1, p2, p3, p4, which represent the respective degrees of belief placed in those statements. For example, the view of a particular climate scientist, Expert A, might be expressed as:

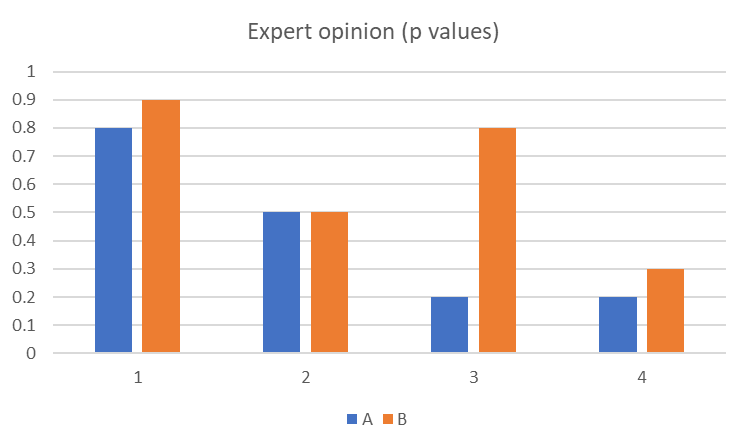

(p1, p2, p3, p4)= (0.8, 0.5, 0.2, 0.2), which means that Expert A is:

- 80% sure that statement 1 – the Earth is warming – is true;

- 50% sure that the warming is life-threatening (statement 2);

- 20% sure that statement 3 is correct – warming is the result of human activity;

- 20% sure that UK NZC will bring about a meaningful global reduction of atmospheric carbon one way or another.

Expert A rates the likelihood of all four statements being correct, i.e., UK NZC being effective, as:

P=p1 × p2 × p3 × p4 = 0.8 × 0.5 × 0.2 × 0.2 = 0.016.

If the view of a second expert, Expert B, with respect to statements 1-4, is:

(q1, q2, q3, q4) = (0.9, 0.5, 0.8, 0.3)

then a comparison with Expert A’s view shows that:

- Expert B has a stronger overall belief than Expert A that UK NZC will be effective (Q=q1 × q2 × q3 × q4 = 0.9 × 0.5 × 0.8 × 0.2 = 0.108, versus P=0.016;

- Both A and B agree that the Earth is warming (p1=0.8; q1=0.9);

- Both of them are equally unsure whether that poses a significant threat to life on Earth (p2=0.5; q2=0.5);

- They differ on the cause of the warming. Expert A doubts that it is man-made, whereas Expert B believes strongly that it is (p3=0.2; q3=0.8);

- Both experts are fairly sceptical that UK NZC will lead to a significant reduction in global atmospheric carbon (p4=0.2; q4=0.3).

Neither expert is all that confident that UK NZC will achieve its aims, with Expert A being particularly pessimistic, seeing the likelihood as just 1.6% compared to 10.8% for Expert B. The main reason is that both of them are doubtful that unilateral U.K. action will have much influence on the choices of other countries.

The chart below represents the view of each expert on each requirement, and highlights statement 3, the one area of significant disagreement.

Summary:

- Defining a view with respect to a set of statements in terms of the respective degrees of confidence associated with each individual statement provides a convenient means of summarising, comparing and illustrating a variety of opinions on the subject to which the statements refer. It also serves as a natural starting point for a cost-benefit analysis of any proposed action.

- It isn’t necessary to be an expert (in this case on climate science) to make a reasonable assessment of the conditions that must apply if an argument or an assertion (such as “There is no alternative to UK NZC”) is to be persuasive.

- It isn’t too much to expect someone – expert or otherwise – who advocates a particular course of action to be able to give rough estimates of the likelihood that the conditions essential to the success of that action will be met.

- Long chains of necessary conditions lead quickly to low probabilities of overall success. The longer the set of plausible conditions that must hold if an assertion is to be true, the less likely the truth of that assertion. With 15 independent requirements, each of which has a 95% probability of success, for example, the probability of overall success is less than 50%. Complex policy issues like those associated with climate change typically have many requirements and much uncertainty.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.